| |

|

|

The key points from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guide

for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure (HF)

from 2021 [1] are presented, as well as some views from the American

ACC / AHA Guidelines from 2022 [2]:

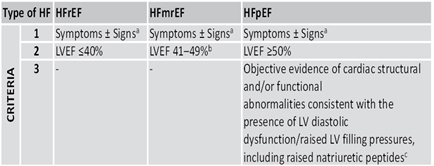

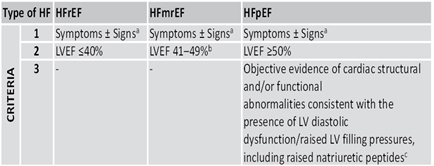

Heart failure (HF) nomenclature with left ventricular ejection

fraction (LVEF) of 41-49% has been revised in HF with mildly reduced

EF (HFmEF). HF with LVEF ≤40% remains HF with reduced EF (HFrEF),

and HF with LVEF ≥50% remains HF with preserved EF (HFpEF).

Table 1. Heart failure (HF) nomenclature from ESC guideline 2021

All patients with suspected HF should have: electrocardiogram,

transthoracic echocardiogram, X-ray of thorax (lung and heart),

complete blood count, urea, creatinine, electrolytes, thyroid

hormones, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), lipid status, iron

analysis, peptide (BNP / NT-proBNP). Magnetic resonance imaging of

the heart is recommended in patients with poor acoustic window for

ultrasound of the heart or in patients with suspected infiltrative

cardiomyopathy, amyloidosis , hemochromatosis, dilated

non-compaction cardiomyopathy or myocarditis [1]. The new diagnostic

algorithm for heart failure (HF) is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. DIAGNOSTIC ALGORITHM FOR HEART

INSUFFICIENCY (HF) ACCORDING TO THE NEW ESC GUIDE 2021.

LEGEND: Heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection

fraction (HFrEF)

Heart failure with mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

(HFmrEF)

Heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF)

Available at www.escardio.org/guidelines (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368)

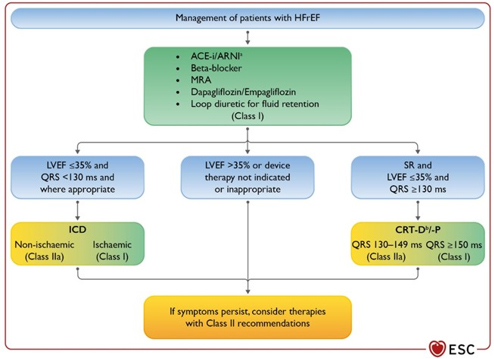

Medical, primarily drug therapy directed by the New ESC Guide,

ie guidelines for patients with heart failure (HF) with reduced

ejection fraction (HFrEF) brings significant innovations and changes

in the treatment paradigm, from the gradual introduction of drugs to

the simultaneous introduction of 5 main classes of drugs.

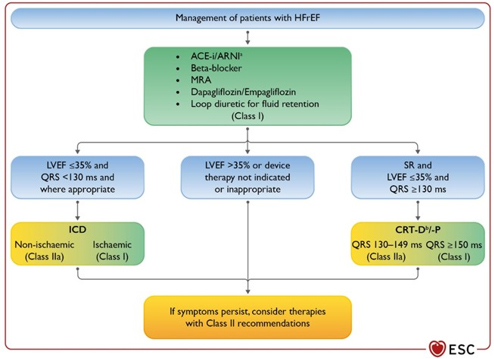

Treatment of heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection

fraction (HFrEF) and symptoms of class II-New York Heart Association

(NYHA) -dispnea at higher exertion and higher classes, now includes

angiotensin receptor inhibitor neprilysin (ARNI) as a substitute for

angiotenzin convertase enzyme inhibitor( ACEI). Another significant

innovation is the addition of SGLT-2 (Sodium Glucose channels

Cotransporter-2) inhibitors, dapagliflozin or empagliflozin in

first-line therapy for heart failure, simultaneously with the

introduction of beta-blockers, ACEI or ARNI, mineralocorticoid

receptor inhibitors and diuretics. class I. (picture 2)

Figure 2. Treatment of patients with HEART

INSUFFICIENCY WITH REDUCED EJECTION FRAGMENT (HFrEF) according to

the ESC guide from 2021

Legend ACE-I = angiotensin converting enzyme

inhibitor; ARNI = angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; ARB =

angiotensin receptor blocker; BB = beta-blocker; CRT-D = pacemaker

for cardiac resynchronization with a defibrillator; CRT-P =

pacemaker for cardiac resynchronization; Available at

www.escardio.org/guidelines (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368)

Excessive neurohumoral activation antagonists, beta-adrenergic

receptor blockers, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

antagonists have shown a reduction in CV mortality in HFrEF in a

number of clinical randomized studies and have been the primary

therapy for heart failure for some time. These drugs achieved the

following beneficial effects: slowing the progression of left

ventricular remodeling, reducing discomfort, improving endurance and

quality of life in all symptomatic categories from NYHA class II to

NYHA class IV. Eplerenone as a selective mineralocorticoid

aldosterone receptor antagonist is recommended for NYHA class II,

while for severe class III-IV patients with beta-blockers and ACEIs

or sartans, a non-selective mineralocorticoid aldosterone receptor

antagonist beparon (beta blocker) should be added with . In

decompensated patients with severe congestion, Henle's loop

diuretics remain a pillar of therapy.

In the treatment of heart failure with reduced LVEF (HFrEF),

sacubitril-valsartan, a combined neprilysin and angiotensin

inhibitor (ARNI), was introduced in previous 2016 ESC guidelines,

which showed an additional reduction in CV mortality and

hospitalizations due to HFrEF compared to the ACE inhibitor enala .

Dapagliflozin and empagliflozin reduce the risk of cardiovascular

mortality or hospitalization due to HF in patients with HF and

reduced left ventricular ejection fraction <40% (HFrEF) [1] but

empagliflozin has also recently shown an effect in HFpEF [65%

ejection] .

In patients with HFrEF and NYHA class II to III symptoms, ARNi is

recommended to reduce morbidity and mortality (class 1A) [3-7].

In patients with previous or current symptoms of chronic HFrEF, the

use of ACEi is useful in reducing morbidity and mortality when ARNi

is not feasible (class 1A) [8-15].

In patients with previous or current symptoms of chronic HFrEF who

are intolerant to ACEi due to cough or angioedema and when the use

of ARNi is not feasible, the use of ARBs is recommended to reduce

morbidity and mortality [16-20].

In patients with previous or current symptoms of chronic HFrEF, in

whom the introduction of ARNi is not feasible, treatment with ACEi

or ARB gives high economic viability [2,21-27].

ARNi is contraindicated in concomitant ACEi or within 36 hours of

the last dose of ACEi, or in patients with a history of angioedema.

Recommendations for the administration of empagliflozin and

dapagliflozin that reduce cardiovascular mortality or

hospitalization due to HF in patients with HF and reduced left

ventricular ejection fraction <40% (HFrEF)

In patients with symptomatic chronic HFrEF, SGLT2i is recommended

to reduce hospitalization due to HF and cardiovascular mortality,

regardless of the presence of type 2 diabetes [28,29] and thus

introduced SGLT2i therapy has good economic justification [30,31].

Recommendations for HF with MILDLY reduced EF (HFmrEF)

In patients with HFmrEF, SGLT2i may be helpful in reducing

hospitalizations for HF and cardiovascular mortality [32]. Among

patients with current or previous symptomatic HFmrEF (LVEF, 41%

–49%), the use of ARNi, ACEi or ARB and MRA and evidence-based beta

blockers for HFrEF may be considered adequate for use to reduce the

risk of hospitalization for HF and cardiovascular mortality ,

especially among patients with LVEF at the lower end of this

spectrum [33-40].

Recommendations for HF with preserved EF (HFpEF) according to the

ACC / AHA guide from 2022 (ref 2)

- Patients with HFpEF and hypertension should be titrated with

antihypertensive drugs in order to achieve the target blood

pressure in accordance with published guidelines of clinical

practice for the prevention of morbidity [41-43].

- In patients with HFpEF, SGLT2 inhibitors may be useful in

reducing HF hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality [44].

- In patients with HFpEF, treatment of atrial fibrillation

(AF) may be helpful in improving symptoms.

- In selected patients with HFpEF, mineralocorticoid receptor

(MRA) antagonists may be considered effective in reducing

hospitalizations, especially among patients with LVEF at the

lower end of this spectrum [45-47].

- In selected patients with HFpEF, the use of ARBs may be

considered to reduce hospitalizations, especially among patients

with LVEF at the lower end of this spectrum [48,49].

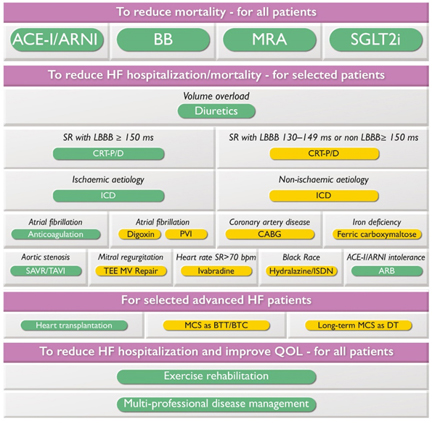

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are recommended

for the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in symptomatic

ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy with LVEF ≤35% despite 3

months of optimal targeted therapy (GDMT) if 1-year survival is

expected. ICD is not recommended within 40 days of myocardial

infarction (MI) or for patients with NIHA class IV symptoms who are

not candidates for advanced therapy.

Cardiac pacemaker resinchronization (CRT) therapy is recommended for

symptomatic HFrEF with EF <35% in sinus rhythm with left bundle

branch block (LBBB) for 150 ms despite GDMT. It is also recommended

for HFrEF with EF <35% regardless of the symptoms or duration of

heart failure if there is a high degree of atrioventricular (AV)

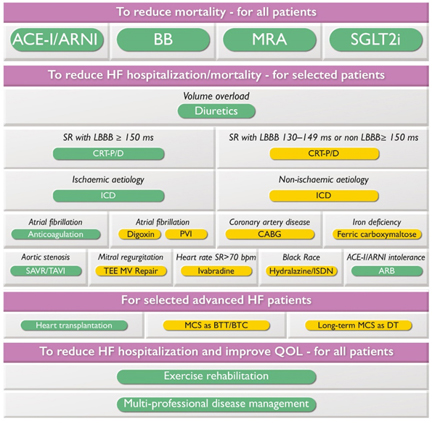

block with the need for a pacemaker. (FIGURE 3)

FIGURE 3. Strategic review of care for patients

with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF)

LEGEND: b.p.m = beats per minute; BTC = bridge to

transplant candidate; BTT = bridge to heart transplant; CABG =

surgical coronary artery bypass grafting; CRT-D = defibrillator

pacemaker resynchronization; CRT-P = pacemaker for cardiac

resynchronization; DT = definitive therapy; ICD = implantable

cardioverter-defibrillator; ISDN = isosorbide dinitrate; LBBB =

block of the left branch of the His bundle; MCS = mechanical

circulation support; MV = mitral valve; PVI = radiofrequency

isolation of pulmonary veins; SAVR = surgical replacement of the

aortic valve; SR = sinus rhythm; TAVI = transcatheter replacement of

the aortic valve; TEE MV repair = transcatheter MV reconstruction

from edge to edge.

Color code for recommendation class: green for recommendation class

I; Yellow for recommendation class IIa. The figure shows the

management options with Class I and IIa recommendations. See special

tables for those with Class IIb recommendations.

Available at www.escardio.org/guidelines (doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368)

For HFmEF, diuretics are recommended to alleviate or eliminate

congestion. ACE inhibitors / angiotensin receptor blockers / ARNI /

beta-blockers / mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists may be

considered as adjunctive therapy to reduce mortality and

hospitalization (Class IIa recommendation).

Diagnosis and treatment of factors that contribute to heart failure

(hypertension, kidney disease, etc.) and the use of diuretics are

recommended for patients with heart failure with preserved left

ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF). Specific therapies have not

been shown to reduce mortality in HFpEF. However, after the release

of the ESC guide (August 2021), a new registration study

Emperor-preserved (2) appeared, where empagliflozin showed

improvement in the clinical outcome of treatment in patients with

heart failure and preserved LVEF> 40%. A pooled analysis of the

effects of empagliflozin 10 mg daily with pre-existing drug therapy

for heart failure was performed on 9,718 Emperor-reduced and

Emperor-Preserved patients. These two studies were comparable so

that a wide range of left ventricular ejection fraction from 25% to

65% was obtained. Studies have shown that empagliflozin reduces the

risk of hospitalization due to heart failure in a wide range of

ejection fraction values by up to 65%, and its efficiency is reduced

in patients with LVEF> 65%. There is also a beneficial effect of

empagliflozin on symptoms and endurance effort consistently with an

ejection fraction of less than 65%. Further analysis found that the

size of the therapeutic response to empagliflozin did not depend on

the size of LVEF in the range of 25% to 65%, with a similar

reduction in HF hospitalization risk to LVEF size in subgroups <30%

and 40-50%, and in the subgroup with preserved left ventricular

ejection fraction> 50%. An important fact from these studies is that

empagliflozin reduces the risk of worsening glomerular filtration (GFR)

in HF along the entire spectrum of the ejection fraction of LVEF,

both with reduced, slightly reduced and preserved LVEF from 25% to

65% (2).

For all patients with HF, enrollment in a multidisciplinary HF

program, at home or at the clinic, is recommended. For the

prevention of HF, Class I recommendations include: appropriate

hypertension treatment, statin use, when indicated, SGLT2 inhibitors

in diabetics at high risk for or with cardiovascular disease, and

counseling to discontinue, consume alcohol and drugs, and treat

obesity.

For acute decompensated HF, routine use of inotropic drugs is not

recommended in the absence of cardiogenic shock, and routine use of

opioid-morphine is also not recommended for cardiogenic pulmonary

edema. Routine use of an intra-aortic balloon pump in cardiogenic

shock after myocardial infarction is not recommended.

Additional Class I recommendations for hospitalized patients with

acute HF include the introduction of targeted oral therapy and the

careful elimination of pre-discharge volume overload (congestion)

with early follow-up within 1-2 weeks of hospital discharge.

For patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), routine use of

anticoagulants for CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2 in men and ≥3 in women is

recommended, preferably with direct-acting oral anticoagulants (NOAC),

except in the presence of a prosthetic mechanical valve or moderate

or severe mitral stenosis. Recommended. Emergency cardioversion is

recommended for patients with HF AF who are hemodynamically

compromised. Rhythm control, including radiofrequency catheter

ablation, should be considered in AF patients who have symptoms.

For patients with HF and severe aortic stenosis, transcatheter /

surgical replacement of the aortic valve using the Heart Time

approach is recommended. For patients with HF with secondary mitral

regurgitation, percutaneous edge-to-edge mitral valve repair should

be considered if severe symptoms persist despite appropriate guided

therapy (GDMT). For patients with secondary mitral regurgitation and

coronary artery disease requiring revascularization, coronary

by-pass and mitral valve surgery should be considered.

Patients with cancer who are being considered for cardiotoxic

chemotherapeutic drugs and who are at risk of cardiotoxicity should

ideally be evaluated by a cardio-oncologist before starting therapy.

Tafamidis is a Class I recommendation in patients with TTR-type

amyloidosis with symptoms of NIHA class I-II.

All patients with HF should be periodically examined for iron

deficiency anemia. Administration of ferric carboxymaltose should be

considered in symptomatic, outpatient patients with HF and anemia

due to iron deficiency and EF ≤45% or hospitalized patients with HF

with EF ≤50%.

REFERENCE:

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al.Citation:2021 ESC

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic

Heart Failure: Developed by the Task Force for the Diagnosis and

Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European

Society of Cardiology (ESC) With the Special Contribution of the

Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J.

2021;42(36):3599-3726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368.

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ,

Colvin MM, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management

of Heart Failure. A Report of the American College of

Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on

Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol.

2022;79(17):e263-e421. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.012. Epub

2022 Apr 1.

- McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al.

Angiotensinneprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart

failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:993–1004.

- Wachter R, Senni M, Belohlavek J, et al. Initiation of

sacubitril/valsartan in haemodynamically stabilised heart

failure patients in hospital or early after discharge: primary

results of the randomised TRANSITION study. Eur J Heart Fail.

2019;21:998–1007.

- Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, et al.

Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in acute decompensated heart

failure. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:539–548.

- Desai AS, Solomon SD, Shah AM, et al. Effect of

sacubitril-valsartan vs enalapril on aortic stiffness in

patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: a

randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322:1077–1084.

- Wang Y, Zhou R, Lu C, et al. Effects of the

angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitor on cardiac reverse

remodeling: meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012272.

- Consensus Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on

mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the

Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study

(CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1429–1435.

- SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in

patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and

congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302.

- Packer M, Poole-Wilson PA, Armstrong PW, et al. Comparative

effects of low and high doses of the angiotensin-converting

enzyme inhibitor, lisinopril, on morbidity and mortality in

chronic heart failure. ATLAS Study Group. Circulation.

1999;100:2312–2318.

- Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moyé LA, et al. Effect of captopril

on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular

dysfunction after myocardial infarction: results of the Survival

and Ventricular Enlargement Trial. The SAVE Investigators. N

Engl J Med. 1992;327:669–677.

- Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors

of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart

failure. The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study

Investigators. Lancet. 1993;342:821–828.

- Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C, Carlsen JE, et al. A clinical

trial of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor

trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after

myocardial infarction. Trandolapril Cardiac Evaluation (TRACE)

Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1670–1676.

- Garg R, Yusuf S. Overview of randomized trials of

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and

morbidity in patients with heart failure. Collaborative Group on

ACE Inhibitor Trials. JAMA. 1995;273:1450–1456.

- Woodard-Grice AV, Lucisano AC, Byrd JB, et al. Sex-dependent

and race-dependent association of XPNPEP2 C-2399A polymorphism

with angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitor-associated

angioedema. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2010;20:532–536.

- Cohn JN, Tognoni G, Valsartan Heart Failure Trial

Investigators. A randomized trial of the angiotensinreceptor

blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med.

2001;345:1667–1675.

- Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, et al. Valsartan,

captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart

failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both [published

correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2004;350:203]. N Engl J Med.

2003;349:1893–1906.

- Konstam MA, Neaton JD, Dickstein K, et al, HEAAL

Investigators. Effects of high-dose versus low-dose losartan on

clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure (HEAAL study):

a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1840–1848.

- ONTARGET Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo KK, et al. Telmisartan,

ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events.

N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1547–1559.

- Telmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACE iNtolerant

subjects with cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators,

Yusuf S, Teo K, et al. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor

blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk

patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors:

a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1174–1183.

- Banka G, Heidenreich PA, Fonarow GC. Incremental

cost-effectiveness of guideline-directed medical therapies for

heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1440–1446.

- Dasbach EJ, Rich MW, Segal R, et al. The costeffectiveness

of losartan versus captopril in patients with symptomatic heart

failure. Cardiology. 1999;91:189–194.

- Glick H, Cook J, Kinosian B, et al. Costs and effects of

enalapril therapy in patients with symptomatic heart failure: an

economic analysis of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction

(SOLVD) Treatment Trial. J Card Fail. 1995;1:371–380.

- Paul SD, Kuntz KM, Eagle KA, et al. Costs and effectiveness

of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in patients with

congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1143–1149.

- Reed SD, Friedman JY, Velazquez EJ, et al. Multinational

economic evaluation of valsartan in patients with chronic heart

failure: results from the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial

(Val-HeFT). Am Heart J. 2004;148:122–128.

- Shekelle P, Morton S, Atkinson S, et al. Pharmacologic

management of heart failure and left ventricular systolic

dysfunction: effect in female, black, and diabetic patients, and

cost-effectiveness. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2003:1–6.

- Tsevat J, Duke D, Goldman L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of

captopril therapy after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 1995;26:914–919.

- McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin

in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N

Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):1995–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303.

Epub 2019 Sep 19.

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, et al. Cardiovascular and

renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N Engl J

Med. 2020;383(15):1413–1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022190. Epub

2020 Aug 28.

- Parizo JT, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Salomon JA, et al.

Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin for treatment of patients

with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol.

2021;6(8):926–935. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.1437.

- Isaza N, Calvachi P, Raber I, et al. Cost-effectiveness of

dapagliflozin for the treatment of heart failure with reduced

ejection fraction. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2114501. doi:

10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14501.

- Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin in

heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med.

2021;385(16):1451–1461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107038. Epub 2021

Aug 27.

- Cleland JGF, Bunting KV, Flather MD, et al. Betablockers for

heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection

fraction: an individual patient-level analysis of double-blind

randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(1):26–35. doi:

10.1093/eurheartj/ehx564.

- Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, et al.

Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with

preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med.

2019;381(17):1609–1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655. Epub 2019

Sep 1.

- Halliday BP, Wassall R, Lota AS, et al. Withdrawal of

pharmacological treatment for heart failure in patients with

recovered dilated cardiomyopathy (TRED-HF): an open-label,

pilot, randomised trial. Lancet. 2019; 393(10166):61-73. doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32484-X. Epub 2018 Nov 11.

- Nilsson BB, Lunde P, Grogaard HK, et al. Long-term results

of high-intensity exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in

revascularized patients for symptomatic coronary artery disease.

Am J Cardiol. 2018;121(1):21–26. doi:

10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.09.011. Epub 2017 Oct 10.

- Solomon SD, Claggett B, Desai AS, et al. Influence of

ejection fraction on outcomes and efficacy of

sacubitril/valsartan (lcz696) in heart failure with reduced

ejection fraction: the Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI

to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart

Failure (PARADIGMHF) trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(3):e002744.

doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002744.

- Tsuji K, Sakata Y, Nochioka K, et al. Characterization of

heart failure patients with mid-range left ventricular ejection

fraction-a report from the CHART-2 Study. Eur J Heart Fail.

2017;19(10):1258–1269. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.807. Epub 2017 Mar 31.

- Solomon SD, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, et al.

Sacubitril/valsartan across the spectrum of ejection fraction in

heart failure. Circulation. 2020;141(5):352–361. doi:

10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044586. Epub 2019 Nov 17.

- Zheng SL, Chan FT, Nabeebaccus AA, et al. Drug treatment

effects on outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection

fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart.

2018;104(5):407–415. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311652. Epub

2017 Aug 5.

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of

bloodpressure-lowering treatment in hypertension: 9.

Discontinuations for adverse events attributed to different

classes of antihypertensive drugs: meta-analyses of randomized

trials. J Hypertens. 2016;34(10):1921–1932. doi:

10.1097/HJH.0000000000001052.

- Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB, et al. Intensive vs

Standard Blood Pressure Control and Cardiovascular Disease

Outcomes in Adults Aged ≥75 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

JAMA. 2016;315(24):2673–2682. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7050.

- SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD, et al. A

randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure

control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103–2116. doi:

10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. Epub 2015 Nov 9.

- Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, et al. Empagliflozin in

heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med.

2021;385(16):1451–1461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107038. Epub 2021

Aug 27.

- Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, et al. Spironolactone for

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med.

2014;370(15):1383–1392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313731.

- Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Assmann SF, et al. Regional

variation in patients and outcomes in the Treatment of Preserved

Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist

(TOPCAT) trial. Circulation. 2015;131(1):34–42. doi:

10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013255. Epub 2014 Nov 18.

- Solomon SD, Claggett B, Desai AS, et al. Influence of

Ejection Fraction on Outcomes and Efficacy of

Sacubitril/Valsartan (LCZ696) in Heart Failure with Reduced

Ejection Fraction: The Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI

to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart

Failure (PARADIGM-HF) Trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(3):e002744.

doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002744.

- Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, et al. Effects of

candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved

left-ventricular ejection fraction: the CHARM-Preserved Trial.

Lancet. 2003;362(9386):777–781. doi:

10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14285-7.

- Lund LH, Claggett B, Liu J, et al. Heart failure with

mid-range ejection fraction in CHARM: characteristics, outcomes

and effect of candesartan across the entire ejection fraction

spectrum. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(8):1230–1239. doi:

10.1002/ejhf.1149. Epub 2018 Feb 12.

|

|

|

|