| |

|

|

1. Introduction

A man's honor is something that stands above life

- Zygmunt Cracow -

Sigmund /Zygmunt/ Krakow was born on 3/15. April 1849 in Warsaw,

from father Ludwik "an old revolutionary from the Polish uprisings

of 1830 and 1863" and mother Pauline (1813-1882) "from the

Radjejowskis, who gave Poland cardinals and marshals, and who

herself was a famous Polish writer" (Krakow, 2004, 28). Her literary

works are: ''Pamiętniki młody sieroty''; ''Powiesci starego wędrowcа'';

''Rozmowy matki z diećmi''; ''Niespodzianka''; ''Wieczory domowe'';

''Obrazy i obrazki''; ''Proza i poezyja polska, wybrana i

zastosowana do uźytku młodzieźy źeńskiej''; ''Wspommenia wygnanki'';

''Nowa ksiaźka do naboźenstwa dla Polek''. According to the father,

the genealogy of the family reached 1665, to Jan Kraków, the bearer

of the ceremonial sword during the reign of King Mihail Wisniowecki

(Stojić 2019, 353). He graduated from Medinica in 1872. at the

University of Heidelberg / "Ruprecht-Karl University"/ with the

grade cum laude superato, earning the title of doctor of medicine

and surgery.

He had a son Ludvik from his first marriage. He had a sister Zofia

and a brother Casimir. After the Polish "January Uprising of 1863",

in 1865 he settled in Paris, working at the Pasteur Institute (Berec

2017, 164). 1885 he came to Serbia as a volunteer in the

Serbian-Bulgarian war, as a military doctor. From the title of

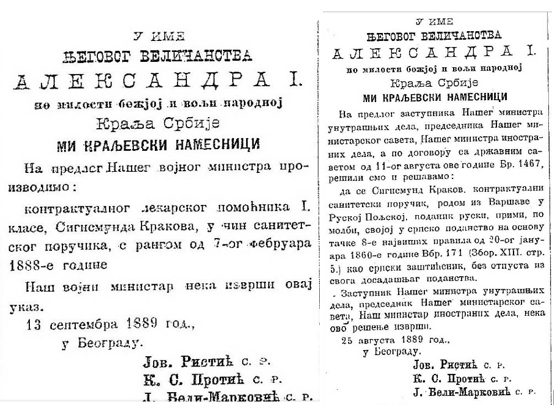

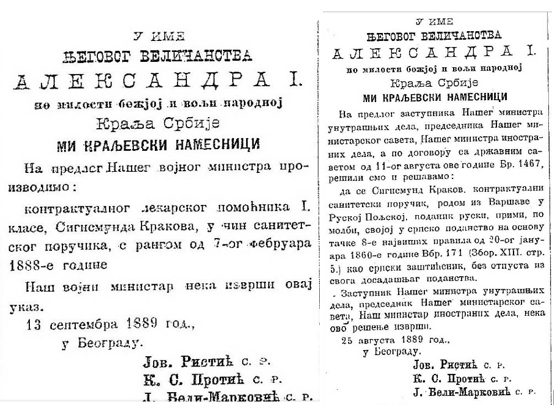

"contractual military assistant" 13/27..9.1889.g. he was promoted to

the rank of "medical lieutenant"

Medical lieutenant of the Lutheran faith, military doctor of the

14th infantry regiment, Sigismund Kraków married a teacher from

Kragujevac, in the extract from the marriage book marked with the

data "Persida Đoković, daughter of Aćima and Pelagija Đokić, born

11/23. November 1869 in Prijeljina''. Commenting on the same

document, Biljana Stojić indicates that it is "Persida Nedić, sister

of Milan, Milutin and Božidar Nedić, distant relative of King Petar

Karađorđević" (2019, 353). Milan Nedić was born from the marriage of

the teacher Pelagia, the "granddaughter of Prince Nikola Stanojević",

through whom they are in contact with the diplomat Konstantin Fotić

and the former Minister of Justice of Kranjevina Yugoslavia and the

leader of the "Zbor" movement Dimitrije Ljotić. It follows that

Sigmund Krakow's wife was the maternal sister of Generals Milan and

Milutin and reserve officer - war invalid Božidar Nedić.

The wedding took place on May 3/15, 1892 in the Church of the

Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Kragujevac. It was

Sigismund's second marriage, her first. On the occasion of his first

marriage and request for divorce, the first-instance court in

Kragujevac addressed 7/19/12/1891. To the Ministry of Education with

a request that it "get all the rules" from the evangelical

pastor-church in Belgrade regarding the fact that the first wife

Mihalina "left Sigismund 6-7 years ago". The Ministry of Education

responded with information dated January 14, 1892. that "in Germany,

the church and the clergy have nothing to do with divorces, because

civil courts do it,... rules printed from an ordinary book are

sent". The marriage was dissolved and the obstacle to entering into

a new one was removed. Stanislav Kraków presents the circumstances

of his parents' marriage as something different. According to him,

Sigismund left his first wife, a Polish woman, and his

eight-year-old son from that marriage in Paris; "since his wife died

in the meantime, he decided to stay in Serbia and get married..."

(2004, 29). In the obituary from 1910. it was announced that he died

after "honoring the act" of military protégé Sava Kelić, to whom the

family expresses special gratitude.

From the marriage of Sigismund and Persida on March 16/24, 1895. was

born on March 16/24, 1895. in Kragujevac, Stanislav, the writer of

the capital works of Serbian literature, "a man with 18 decorations,

14 wounds, three death sentences" (Stojić 2019, 350).

As published by "Male novine" from September 13, 1899. "Sigmund

Kraków, contractual medical lieutenant, native of Warsaw, Russian

citizen" received Serbian citizenship.

As required by the service, he was assigned to military garrisons in

Kragujevac, where he served in 1897-1898. was also the manager of

the surgical department of the military hospital, then in Niš /from

April 21-May 4, 1901/, Leskovac /from October 12-25, 1901/,

Knjaževac /from May 8-21, 1902 /, Zaječar, Kladovo /from September

9-22, 1903/, Belgrade /from November 13-26, 1907/.

According to the order of the Minister of Military No. 3595 of

September 9/25, 1903, according to the needs of the service,

"medical lieutenant Sigismund Kraków, until now the corps doctor of

the Knjaževac garrison, was appointed as the corps doctor of the

Kladovo garrison." Stanislav Krakow wrote about his arrival and life

in Kladovo:

''… My father was suddenly transferred from Knjaževac to the border

fortress of Kladovo on the Danube. He was satisfied with this change

because in Kladovo he had to be not only a military doctor but also

the only doctor for the entire area. Like in the Wild West, we

traveled for three days in a closed carriage from Knjaževac to

Kladovo by the border river Timok and then through the dense oak

forests in the Krajina that were never without hajduk... It was

already the third night since we left Knjaževac when we saw the

lights the small fishing town of Kladovo. Our carriage bounced over

the old Turkish cobblestones. He stopped in front of a hotel, which

only had a ground floor.

The curious inhabitants of this small town of fifteen hundred souls

began to gather around the carriage: - The doctor has arrived. Just

at that moment, the door of the tavern opened and the owner of the

hotel ran out excitedly:

- Doctor, quickly, save my wife... As my father had his briefcase

under his arm, he ran into the tavern. We sat in the carriage and

waited. A little later I saw my father coming out smiling. The

hotelier's wife got a fish bone stuck in her esophagus and started

to choke. My father removed her bone and his reputation as a good

doctor was already established on the first night.

The next day we drove into the old Turkish fortress of Fetislam, a

few kilometers from the town, where there was a garrison of several

hundred people. We drove over the suspension bridge and by the heavy

iron gate a guard came out to pay respects to my father...

We got a large separate house, which here, like in the colonies,

because of the many snakes, was built so high that it had to be

entered via several stone steps. At first, snakes were a real

nightmare for me, and for my mother during our entire stay in

Kladovo. I got used to them over time. They were everywhere. Every

day we found them in the pantry and the kitchen, which were in a

separate building, where they were looking for milk, hanging from

the ceiling beams, crawling under cupboards, getting into crates. In

the barn where my father's horse was, Seiz was never allowed to put

his hand in the hay, lest he come across a snake. But most of them

were between the stones of the huge city ramparts, under which there

were deep casemates, which used to serve as a prison. It was in the

casemate, the one closest to our house, where we kept chickens, that

the later famous Serbian statesman Nikola Pašić was imprisoned after

the rebellion of Eastern Serbia in 1886 against King Milan.

For me, the Kladovo fortress was the promised land. The presence of

a large number of soldiers, in whose life I liked to interfere and

share it, huge cannons on the bastions, a citadel in the middle of

the fortress, with high towers and a suspension bridge, which could

only be entered barefoot or in slippers because it was full of

dozens of tons of explosives and gunpowder, underground lagumi, all

that was miraculous for me. The largest number of civilian patients

of my father were alasi - fishermen, and that's why he was always

full of caviar and the best Danube fish. Fishermen taught my mother

to roast kechiga, wrapped in parchment, on a spit over low heat, and

it became my favorite dish.

That's where I first came into contact with abroad - if you can call

it that, Kladovo was on the triple border. I often crossed by boat

to Turn Severin, in Romania, or to Orshav, just a few kilometers

away, in Austria-Hungary. And between those two foreign countries

for me, I discovered another one: Turkey. Better to say, a lost part

of Turkey. There, near Oršava, in the middle of a river full of

eddies, like an enclave, was the small fortified island of Adakale,

the last remnant of Turkish rule on the Danube. When I disembarked

for the first time from a large fishing boat, which could hardly

maintain its balance in the midst of strong rapids, into the

greenery of this small island, it was as if I had come to a country

that was from another era and from another continent. Adakale

theoretically belonged to Turkey, but there was no government at

all, except for one head of the town, who was like the head of a

large family. Not the police, not the customs, not the court, not

the hospital. People lived a quiet, unchanged life. They watered

their gardens and looked after a few sheep and then came to the

center in front of the only tavern, under the blossoming trees, to

sip coffee or eat rahatlokum there. Life had completely forgotten

about them... It was only after the Balkan Wars /1912-13/ that

Austria-Hungary settled the island and introduced it to all the

obligations, laws and duties that a modern state imposes on its

subjects..

In the summer of 1906, I finished the fourth grade of the elementary

school in Kladovo as the best student. The director of the school,

Milić, was a grateful patient of my father. I was supposed to travel

to Belgrade in the fall to stay with my grandmother and uncle in

order to study high school there. That was the last summer of my

happy childhood in the Kladovo fortress...'' (2004, 19-21).

In the same year, King Petar appointed Dr. Sigismund as his personal

physician during treatment at the Brestovačka Banja. Stanislav

Krakow concludes his impressions with the words: "when, after more

than a month of treatment, King Petar left Brestovačka Banja, my

father followed the royal caravan on horseback. The large and dense

dust that rose from the country roads when so many carts passed, and

in which he rode for days, made my father, when he came to Belgrade

with the king, suddenly spit up blood. And when I met my father in

the Kladovo fortress, after returning from the capital, he brought a

signed picture of the king, fifty gold coins, toys and books for me,

but also the beginning of tuberculosis'' (2004, 24).

In the Kladovo fortress there was a hospital and a pharmacy,

especially the "marvena pharmacy", as Jovan Mišković noted during

the control inspection carried out on October 3, 1884; in addition,

he also gives a description of the fortress: "The city of Fetislam

is mostly four-sided with 6 bastions /4 on the longer, dry side, and

2 on the corresponding Danube side/, 3 gates and 2 brick round

towers facing the Danube. There is a visible redoubt in the middle,

with two round towers on the land side. It has a powder store on

vaults in two compartments. Besides that, a small hand magazine. The

casemates are unusable. There are two out-of-the-ordinary barracks:

1 battalion, and the other one for provisions. Apart from that,

about 10 buildings of various sizes and values'' (2020, 2, 116). The

fortress is also known for the fact that the latter General Kosta

Milovanović, commander of the artillery in Fetislam in 1877, served

there. and Duke Živojin Mišić - posted here for duty in 1890. as

general staff captain first class, 1893. /then in the rank of major/

Colonel Panta Trifunović, father of the divisional general and

Minister of the Army and Navy of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Dušan

Trifunović.

At the level of the Ključki district in the period 1903-1907, unlike

other districts of the Krajinski district, no one was assigned to

work in the health profession, so the presence of Dr. Sigmund Krakow

meant a lot to the population (Blagojević 2005, 284-333). The

presence of another Pole, Siegfried Policer, a pharmacist in the

small border town, was of great importance for healthcare in the

Kladovo area. Starting from 1906. he ran a pharmacy at the beginning

of Kralja Aleksandra Street, equipped according to the highest

standards. A herbarium was located in the specially designed

apothecary's attic for the storage of herbs intended for the

production of medicines. Medicines were kept in a part of the

basement partitioned with stone. The pharmacy was characterized by

spaciousness and light. In Kladovo, Dr. Sigismund also found the

famous pharmacist Jozef Dilber (1828-17-5-1905), a graduate

pharmacist from the University of Prague, the owner, the first

president of the Pharmaceutical Society of Serbia, who ran a

pharmacy here until 17-5-1905.

In the official military gazettes of 1903-1907. there are data on

the humanitarian activities of Dr. Krakow through the work of the

Red Cross. According to the Report on the activities of the Serbian

Red Cross Society 1.1. In 1907, together with him, the following

officers of the Kladovo fortress did it: lieutenant colonel

Svetozaar Protić, captain II.cl Pavle Jakovljević, lieutenants Milan

Matijević, Dobrivoje Mojsilović, Svetozar Ristić and lieutenants

Dragiša Predić, Radoje A Pantić and Milivoje Alimpić.

By order of the Minister of Military No. 9320 dated 13/27. In

September 1907, instead of medical lieutenant Josif Radulović,

Sigismund Kraków, "so far a corps doctor in the command of the

Kladovo fortress", was appointed acting corps doctor of the

Eighteenth Infantry Regiment of "Kraljević Đorđe, the Crown Prince"

and manager of the temporary spa infirmary.

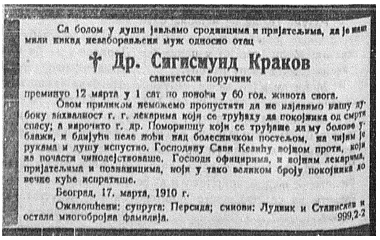

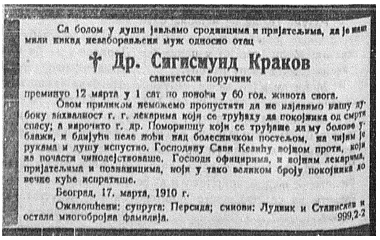

He died in Belgrade on March 12, 1910. On this occasion, an obituary

was published in the Serbian press: "It is with pain in our hearts

that we inform our relatives and friends that our dear,

never-forgotten husband or son, Dr. Sigismund Kraków, medical

lieutenant, died on March 12 at 1:00 a.m. at the age of 60. his own.

On this occasion, we cannot fail to express our deep gratitude to

Mr. to the doctors who tried to save the deceased from death, and

especially to Dr. Pomorišac, who tried to relieve his pain, and

vigil all night over the patient's bed, on whose arms he lost his

soul. Mr. Sava Kelić against the military, who acted out of honor.

Lord to the officers, and military doctors, friends and

acquaintances, who escorted the deceased to their eternal home in

such a large number. Belgrade, March 17, 1910. Mourners: wife

Persida, sons Ludvik and Stanislav and other numerous relatives. The

places of service in Timok - Knjaževac, Kladovo, Zaječar have not

commemorated dr. Sigismund Krakow was extracted through several data

in the publication "150 years of the Hospital in Knjaževac

/1851-2001/" by Dragan M Ivanović Šakabenta (2001).

There is a wikipedia entry about his son Stanislav: Kraków is a man

of wonderful life and idea verticality. He was always rightly

determined and consciously sacrificed for the Serbian idea. He was

an example of how to fight, how to write, how to act politically and

how to believe in courage. In it, a synthesis of a national, modern,

traditional, right-wing and brave Serb was created, who with his

example negates the thesis of local writers that only anti-national

writing in the genre range from "post-Titoism" to anti-war adulation

is the only Serbian literature that is worthwhile and that rules the

local scene.

He is the holder of the decorations: White eagle with swords, 4th

degree; two gold medals for bravery; Officer of the Romanian Crown;

bearer of the Albanian monument; The cross of mercy.

In 1944, he emigrated to Austria, and then to France, where he

continued to live. In Belgrade, he was sentenced to death by firing

squad in absentia.

He died as a forgotten emigrant in Switzerland, on December 15,

1968, in complete misery.

* For the help in collecting the material, which we present in the

attachment, the author owes special thanks to the Archives of

Yugoslavia, Belgrade, and to Mr. Mirko Demić, director of the

National Library "Vuk Karadžić", Kragujevac

SUMMARY

This paper presents biographical data and details related to

service and life in Kladovo in 1903-1907. Dr. Sigismund Krakow and

his ancestors. With his personal generosity and high moral views, he

made a significant contribution to the development of healthcare in

Serbia.

LIST OF SOURCES AND LITERATURE:

- Ratko Blagojević editor in chief, Schematism of the

Krajinski District 1839-1924, Negotin Historical Archive 2005.

- Nebojša Berec, In the Footsteps of Stanislav Krakow,

"Brotherhood" edition of the Sveti Sava Society, Belgrade, 2017;

21.

http://doi.fil.bg.ac.rs/pdf/journals/bratstvo/2017/bratstvo-2017-21-10.pdf.

- Dragan M Ivanović Šakabenta "150 years of the Hospital in

Knjaževac /1851-2001/", Health Center Knjaževac 2001.

- Stanislav Kraków, The Life of a Man in the Balkans, "Our

Home", Belgrade, 2004.

- Jovan Mišković, Diary records 2 volumes, Negotin Historical

Archive 2020.

- Biljana Stojić, STANISLAV KRAKOV IN THE WARS FOR LIBERATION

AND UNIFICATION (1912–1918) HISTORICAL JOURNAL, 2019; LXVIII:

349–382. UDC:94(497.11)"1912/1918":929 Kraków S. DOI:

10.34298/IC1968349 https://www.iib.ac.rs/istorijskicasopis/assets/files/IC1968349.pdf

приступљено 25.6.2023.г.

- "Male novine" 1/9/1899 - news about admission to the Kingdom

of Serbia

http://istorijskenovine.unilib.rs/view/index.html#panel:pp|issue:UB_00031_18890901|page:3|query:%D1%81%D0%B8%D0%B3%D0%BC%D1%83%D0%BD%D0%B4%20%D0%BA%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2

- Order of the Minister of Military. Official military paper.

May 1902; 391-392.

- Order of the Minister of Military. Official military journal

1901; 967-968.

- Order of the Minister of War. Official military gazette

16.11.1907;.711-712.

- Report on the activities of the Serbian Red Cross Society

1.1. 1907;152.

https://pretraziva.rs/pretraga?search=%D1%81%D0%B8%D0%B3%D0%BC%D1%83%D0%BD%D0%B4+%D0%BA%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2&advanced=

Diploma transcript, Archives of Yugoslavia

Extract from the marriage register, Archives of Yugoslavia

Diploma of Ludvik Krakow, Archive of Yugoslavia

|

|

|

|