| |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

Dr. Hunter's work, according to medical historians, in combating

the epidemic was generally unsuccessful. The same historians

examined the work of the Serbian sanitary service [1]. Evaluations

made in 1915 and 1925 were also reviewed. After the discovery of the

causative agent of plague and Nikola's Nobel Prize, earlier

uncertainties needed resolution. Dr. Vuksic noted in 1989 that Dr.

Hunter played an impressive role as a leader in combating the plague

in Serbia. He pointed out the contribution of Dr. Hunter and his

team [2]. This alone indicates the unsustainability of denying the

success of 1915. At that time, no significant action by the Serbian

sanitary service was noted; instead, it was considered to be within

the scope of Dr. Hunter's and other foreign missions' activities.

Chief Sanitary Officer Dr. Genchic insisted to the Serbian

government on January 15, 1915, that "the profession needed to be

strengthened." The government adopted the proposal, resulting in

success. Regarding Dr. Genchic's address on January 15 in his new

methodological approach to studying the Great War through archival

material, Dr. Nedok states: "This report concludes the reporting of

the Chief Sanitary Officer Dr. Genchic to the Chief of Staff of the

Supreme Command, Vojvoda Putnik..." after which "the epidemic

waned... By the end of May 1915, a period of respite and recovery

will occur..." Dr. Nedok concludes his evaluations with biographical

data on Dr. Genchic, who is "criticized" [3].

In his discussion (attached to Dr. Subbotic's presentation), Dr. J.

Berry (James Berry) emphasizes the possibility of uncertainty

regarding the success of epidemic control. The success of control

after the plague epidemic gained momentum is also questioned, i.e.,

that it is not the same as control that was "timely initiated"

[4:38]. No answer is given as to why the epidemic gained momentum..

Measures in combating the epidemic by the Serbian sanitary service

were achieved through the implementation of administrative measures

- interruption of railway traffic. The first measure was requested

on March 10 - "it came into force on March 16 and lasted for two

weeks... it was supposed to expire on March 30."

The second measure, the suspension of other traffic, followed the

first and lasted until April 16 (according to the Gregorian

calendar). Dr. Hunter takes over a significant portion of medical

responsibilities from the Serbian sanitary service starting from

March 16, thus beginning the "English side" of combating the plague

epidemic and return [5].

Some assessments of the work of the Serbian sanitary service in 1925

were disagreed upon by contemporary Dr. Žarko Ruvidić (war sanitary

general). The criticisms he pointed out in 1947 were primarily

methodological. Due to insufficient argumentation, he disagreed with

the given assessments of former chiefs [6]. It has already been

shown that Dr. M. Pecic, who combated the epidemic, successfully

ended it in its epicenter, in Valjevo [7]. Dr. Pecic and Dr. Ruvidić

were awarded in 1915. This was a new reason to doubt the correctness

of the negative assessments pronounced in 1925 regarding the work of

the Serbian sanitary service. Re-examining the defeatism of the

actors [10], assessments of the outbreak of the epidemic are

primarily the result of the impotence of medicine exacerbated by

war, i.e., "war typhus," and plague.

A way to combat it was sought, and incidentally, the main reason for

the outbreak was implicitly found. It was the initial contribution

of Dr. Subbotić, i.e., his "buried furnace" [8,9]. Who supported the

Serbian sanitary service? How can this be proven today? The

hypothesis is that those who were awarded in 1915 contributed to it.

Negative assessments of the work of the sanitary service expressed

in 1925 call into question the honor of the awarded doctors. A

retrospective analysis of the success of the awarded officers of the

Serbian sanitary service will be made. Historians' conclusions about

medicine are subject to scientific verification. The assessment by

the strength of arguments can be confirmed, modified, or rejected.

Are general measures sufficient? Why were they not properly

implemented? The increase in the epidemic led to unrest. Fear of

failure had already gripped the doctors of Serbia since January and

February, hence the request for assistance from the allies. As the

response was uncertain, Serbia contemplated the epidemic that had

befallen them. They did not give up. Isolating the sick alone needed

to be reconsidered as a strategy.

If the actors after the Great War were correct in seeking the

reorganization of military and civilian sanitation, it does not mean

they pinpointed the correct cause of the high mortality rate in the

epidemic. The cause was not the organizational weakness of Chief Dr.

Genchic. He contributed to the special epidemiology of typhus by

combating the lice infestation [3,12]. The problem was how to solve

the advancing epidemic, as seen by Dr. Berry while working with his

wife in Vrnjačka Banja. The uncertainty of success in combating the

epidemic emphasized by Dr. Berry in the conditions of epidemic

spread raises the question: were there conditions for timely

suppression? Did the English mission and Serbian sanitation reflect

on the same?

It is noticeable that there are differences in the activities of the

Serbian sanitation during the epidemic and what Colonel Dr. Subbotić

wrote about it in his presentations in Paris and London [4]. There

is an inconsistency in interpreting the same events. It's as if one

truth applied to foreign countries, where Dr. Subbotić was

presenting, and another in the homeland. Therefore, despite the

dominance of memories in 1925, the published literature dealing with

the issue of epidemics in Serbia during the Great War, such as the

works of Strong, Hunter, Subbotić, etc., is not utilized. Despite

these weaknesses, the chief of sanitation is attributed with the

following: "Dr. Genchic was a participant in liberation wars and a

member of the Supreme Command. His work was criticized due to

untimely and inadequate measures against the epidemics of typhus and

dysentery, resulting in massive losses in the army and among the

people." [12;13:190]. By automatism, the writer-doctors, as actors,

have also assessed themselves. If so, because of the plague (and

that was a criticism), the question is whether the doctors deserved

the awards given in 1915.

Engagement of the Royal Mission's sanitation in combating the

epidemics. Dr. Hunter found an advanced epidemic upon arrival, as

indicated by the number of hospitalized patients. The peak was

reached one month after his mission's arrival. This corresponds to

Dr. Berry's observations.

The untimely activity of the Serbian sanitation - The consequence of

the untimely implementation of measures is registered by Dr. Hunter

in his book. He was familiar with the period preceding the arrival

of the mission. Several facts will be presented as he noted them:

"There were two types of problems - a clinical problem concerning

the improvement of accommodation. The other... a preventive problem

to stop further spread of infection to the healthy." [5:108]. Hunter

believes that "seeking help from doctors from our government and

others, it is undoubtedly, in my opinion, that the guiding thought

of the Serbian authorities was to obtain as much of the much-needed

clinical help as possible" [5:237-8]. The basis was seen: "Hospital

conditions were indescribably poor; overcrowded, without any

sanitation plan; without disinfection measures..." The urgent need

was for beds, mattresses, bedding, pajamas, clothing for a mass of

15,000 infectious patients [5:99]. The summary would be: "The state

in hospitals was overcrowded and shockingly unhygienic" [5:238].

Other reasons were present: poverty, untimely provision of money,

total war, etc.

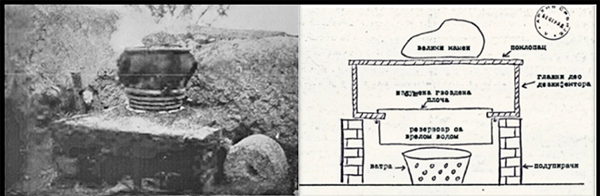

The English Royal Sanitation Mission of Dr. Hunter proposed measures

in nine points, including the use of the "improvised autoclave": a

wooden chamber placed above a boiler. A stationary fire heats the

water (principle of moist hot air) - (Figure 1) [12]. Then they

supplemented them with a new proposal for the interruption of

passenger railway traffic [5:113,119,121].

Protich believed that Stamer's improvisation was applied in the

Russo-Japanese War of 1905 [14]. Dr. Genchic appointed him as the

representative of the Serbian sanitation during the testing of

Stamer's improvisation. An order was issued for the production of

these chambers at the Military-Technical Institute (VTZ) in

Kragujevac [5:219]. The next change was proposed by Stamer: a metal

barrel was used instead of a wooden crate, so this was the

definitive variant of the improvisation made by VTZ, known as the

"Serbian barrel" [12].

Image 1. Left: The furnace used in Japan in 1905

(found according to Dr. Đ. Protić's references) [12:104]; Right:

Sketched prototype of Stamer's proposal for an improvised autoclave

made of wood: a) box (drawn) and b) "barrel" (notated) [12:101

Upon arrival, Dr. Hunter was briefed on the preceding events of

the epidemic. As these activities in 1919 are partially depicted,

predominating are the pieces of information about the epidemic's

growth, while activities of the Serbian sanitation to resist the

infection are unknown to him.

Assessments of the success during the war - The assessment from 1915

is "astonishingly thorough," although unofficial. Primarily, it

referred to Hunter's work in Mladenovac. The route from the war zone

of Valjevo led by narrow-gauge railway to Mladenovac. Other traffic

was not functioning. In Mladenovac, Hunter implemented a

disinfection station: quarantine and a cleansing center (bathing and

delousing), as well as treatment by bringing in mobile hospitals

(under tents). The progression of the epidemic was successfully

halted by traffic bans and finding ways to protect healthy soldiers

from typhus spreading from Valjevo, known as an "epidemic focus"

[15]. The Serbian sanitation also had its judgment about the

significance of Hunter's team's work - expressed by the chief. It

wasn't just courteous, but more than that - a substantial

assessment, which would be agreed upon today.

On May 25 (June 7), 1915, Colonel L. Genchic sent a congratulatory

letter to Dr. Hunter for leaving Serbia and embarking on a new task:

"Although you and your mission have worked only for a short time,

exceptional results have been achieved. The assistance your mission

provided us in every aspect, under your experienced leadership, will

stand at the forefront of all the foreign aid we have received in

this war... (emphasized, GC)" [5:248,251]. This assessment did not

differ from Dr. Vuksic's assessment expressed in 1989 and was not

sufficiently emphasized.

These commendatory assessments debunked the assessment from 1925

about the importance of warmer weather. Consequently, the decisive

activity of the doctors was supported, justifying the proper

awarding of honors to members of the English Royal Mission.

[16:735].

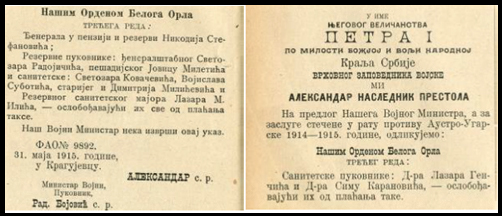

Figure 2. Decorations of Serbia awarded to members

of the Medical Mission of the Royal Army in Serbia [16:735]

The assessments of Hunter's contribution are commendable, but

domestic successes have been neglected.

Dr. Subbotić's work was published in 1918. Hunter, in 1919, does not

cite this work, although it was presented in English. In his

published presentation, he mentions his "underground stove," as well

as the use of other chambers with warm dry air and bathing

facilities. This seems inadequately emphasized, somewhat clumsily

expressed. This is not the case when he points out the advantage of

the dry chamber compared to the "Serbian barrel." He also discusses

the endemic nature of typhus and the possibility of its importation

from neighboring countries such as Albania and Bosnia. Initially,

differential diagnosis of typhus posed difficulties.

It is interesting to note the participation of the Berry couple in

the discussion, who were in Serbia during the epidemic. The use and

description of the chamber with warm dry air, similar to a dugout,

is highlighted more clearly than what Dr. Subbotić did. This was

first seen and presented in Russia. Supported is also Dr. Subbotić's

experience that a deloused patient is non-infectious to the

surroundings, and the procedure is outlined as to how this

conclusion was reached when the disease is discovered among

hospitalized patients [4:38-9]. This is significant evidence that

the human body is crucial in transmitting the causative agent of

typhus, thus supplementing Nikolay's observations based on

experiments on monkeys.

Chapter on the engagement of Serbia's sanitation in combating

epidemics will be explored through questions:

a) experience with freckles before the 1915 epidemic;

b) the importance of a mild climate, warm weather, on stopping the

epidemic;

c) the interrelationship between the actors of the writers (1925),

Hunter (1919) and Subbotić (1918).

The essence of the necessary reorganization of Serbia's sanitation

was different from the perspectives of the actors. General

preventive measures were insufficient. They had to be replaced by

"specific measures". The strategy for combating typhus was

deliberation. This insight is valuable for the future Nobel Prize

awarded to S. Nikola. Dr. Genčić personally contributed to this

direction of Serbian sanitation, as seen in his address to Vojvoda

Putnik on January 15 [3,12]. Dr. Subbotić elaborated on the reasons

why a certain number of actors did not consistently accept that lice

transmitted typhus [4:38]. They could not consider delousing useful

for either the sick or the healthy – it just needed to be proven or

accepted as having epidemiological significance. So, until then,

they were just pests to be removed like any other dirt (unhygienic

condition).

At the beginning of the epidemic, a set of facts was noticed that

contributed to the spread of typhus. The first is essential: typhus

was an unknown disease in medicine. There was a lack of tactical

means for mass use. The second fact builds on the previous one,

namely the "conditions for the development of such a massive

epidemic created by a severe war."

Chapter on the engagement of Serbia's sanitation in combating

epidemics will be addressed through questions:

a) Experience with typhus before the epidemic of 1915 - Borjanović

in his thesis in 1977 believes that "typhus in Serbia before the

First World War was not a health problem, as there were no endemic

foci of this disease." He declaratively states the existence of

typhus in 1836 in Kragujevac, the then capital of Serbia, without

offering arguments on how it was recognized [17:193]. Thus,

ambivalence is spoken about the endemicity, as much as it existed,

as it was not [18].

It was believed that typhus in Serbia persisted in a chain of acute

cases in specific groups. That it "... appeared only among Gypsies

without a permanent residence and in a few cases in prisons" [19].

Criticism was raised due to one-sidedness, for supporting only the

teaching that preceded the establishment of the existence of

recurrent typhus, "for which explanations had to be found," such as

permanent beds [18]. Such an approach was not taken by Dr. Kuzelj.

He was more correct as he was more biological, insisting on

similarities among people rather than differences.

The occurrence of the epidemic among guardsmen in 1836 in Kragujevac

has not been studied more studiously. Therefore, it has not been

proven which "typhus" was present; or if a type was specified,

arguments were not given for such naming [18]. The typhus that

appeared in the Topčider prison in 1906 was not even described, so

crucial judgments as experience were not drawn [20]. There was also

double reporting of the disease. Official statistics collected data

recorded by priests in death books. Until the end of the First World

War, combating infectious diseases fell within the jurisdiction of

district, county, and city doctors – physicans [21:17]. Physicians

sent their reports on the movement of infectious diseases to the

Ministry of Health, Sanitary Department. This issue was "resolved"

by wartime events. In 1913, the last annual report for 1907 and 1908

was published [22,20,23], while for 1909 and subsequent years they

were not even published..

b) Mild climate, spring, warm weather - During the Balkan Wars, the

experience was: "...During the winter of 1912/13, when our Serbian

Army units crossed Albania to the sea and reached Durrës... the

first cases of this disease appeared among them and became much more

frequent than in other units. Deaths were not lacking. At first, we

attributed them to fatigue, exhaustion, and shortages, but soon it

was noticed that we were dealing with a very characteristic disease

face to face with an enemy previously unknown to us. These were

typhus and relapsing fever, two diseases endemic in Albania. The

number of those who contracted these diseases was relatively small;

only a relatively small number of doctors knew about them. As soon

as the weather became nice, these diseases disappeared on their

own." [24:3; 4:32].

It is noted that the spread of typhus is contributed to by its

difficult detection, differential diagnosis with other diseases or

conditions. It was emphasized: fatigue, abdominal typhus, etc. This

is what doctors in contact with patients in basic units had to pay

attention to, and it is important for the entire sanitation.

Antic states how the "authorities" who did not spare us with

countless "orders" missed to inform us of one similar order,

ordering us to know that soldiers spread typhus. There is no doubt

that there was such a conviction among doctors, as well as among the

rest of the army, that the number of victims of typhus in the army

and among the people would have been significantly lower. [25:322].

Antic believed that the epidemic was stopped by the arrival of

spring, naturally; and not by the influence of measures [25:319].

Like Subbotić, Antic also points out that there were doctors who

doubted the correctness of the truth that soldiers spread typhus.

According to him, neither Dr. Hunter believed in all of this, as he

wore a handkerchief instead of a protective mask, thus showing that

the transmission of the typhus pathogen is possible through the air.

But, others also thought the same. In the article "Serbia, Land of

Death," Reid described Serbia as: "...the land of typhus -

abdominal, relapsing fever, and mysterious and cruel typhus (in

English, he is "typhus"; and "typhoid" is abdominal, G. Ch.), which

kills fifty percent of its victims and whose bacillus had not yet

been found by that time. Most doctors thought that it was spread by

white lice, but a lieutenant of the British Royal Army Medical

Corps, who traveled with us, was skeptical. I was there for three

months - he said - and I have long ceased to take any precautionary

measures except for daily bathing. And as for lice, a man gets used

to spending a pleasant evening brushing them off one by one... The

truth about typhus is this: no one knows anything about it, except

that one-sixth of the Serbian people died from it... Warm weather

and the cessation of spring rains had already begun to stop the

epidemic - and the virus weakened. Now there were a hundred thousand

sick people with typhus in the whole of Serbia and only a thousand

deaths per day - except for cases of horrible typhus gangrene."

[26,9].

Events in the Great War were memorable and unforgettable. In a

commemorative brochure reflecting on that time, it was noted: "The

epidemic of typhus in Serbia, which during the First World War

placed us in an unfavorable position in the history of medicine,

could not be thoroughly studied or described... Today, there are few

doctors in life who served in the sanitation service of Serbia

during the First World War, but those last witnesses of the great

typhus epidemic of 1914 and 1915 still vividly remember the sudden

appearance and dramatic spread of this serious disease among the

ranks of soldiers and civilian population. The catastrophic

consequences of that epidemic left a mark in their memories as one

of the most painful events of that difficult time. Typhus was

introduced by the Austrian army and masses of enemy prisoners from

Bosnia into Serbia, where all the conditions for the development of

such a massive epidemic were created by a hard war." [20:34]. With

the departure of the actors from the world stage, Serbian doctors

were supposed to complete the description of the "typhus epidemic in

Serbia".

From the foregoing, it can be seen that in Serbia, in peacetime, the

people's activities prevented typhus from becoming a problem that

imposed itself with its special significance. At the beginning of

the epidemic, it persisted because it was difficult to diagnose. It

was believed that "typhus, as it came, would also go", spontaneously

without major casualties. Experience provided evidence that typhus

would not be a bigger problem, and those rare cases (sporadic ones)

would incapacitate by the first spring [12:19]. In the archives of

the sanitation department of the Supreme Command, evidence

supporting such thinking was not found. Contrary to this...

Memories from 1925 indicate that such expectations prevailed among

physician writers, as seen in their final conclusion explaining the

end of the 1915 epidemics: due to the upcoming warm season, they

ceased naturally, rather than through undertaken efforts to combat

them [12:29,135].

Capur is probably closest to the truth as he believes in 1875 that

the medical personnel's imperfections stem from "a lack of patience

and perseverance for deeper and more thorough immersion in certain

matters, or specific fields... This is a common occurrence among

people taking their first steps towards cultural development. They

simply don't yet have the need to be thorough scholars. Practical

knowledge, useful for their current needs, is entirely sufficient

for them at first" [11:49]. Serbian doctors were aware of these

facts. They advocated for the establishment of a medical faculty.

Poor personnel preparedness was emphasized not only in terms of

quantity but also regarding specialization. Trouble ignites a spirit

whose scope is difficult to measure accurately in wartime

conditions, with the presence of a not insignificant number of

"scientific unknowns."

Unlike the stance of the actors, Dr. Genčić, with the Infection

Control Commission at the Supreme Command, as well as the State

Committee for Infection Control, advocated for undertaking

activities that respected the body's resilience. The only question

was - how to manage them. Dr. Subbotić pointed this out in 1916

[24], which was published in 1918 [4].

c) The interaction between the actors, the writers (1925), Hunter

(1919), and Subbotić (1918), shows that Dr. Hunter acted as a

scientist, which simultaneously connected him to the history of

medical science. He commented on the scientific contribution arising

from improvisation: "The problem of providing a simple and effective

method of disinfection, accessible to everyone and for the needs of

the railway, has been solved, not only now, but for all times

(emphasized by V.H.)." [5:248]. Therefore, the "Serbian miracle"

emerged. With such actions, there were conditions that could provide

a solution, which Dr. Hunter utilized as an organizer. Dr. Subbotić

also acted in this direction, solving the impotence through

improvisation, offering his "buried stove" (for dry warm air)

[4,12]. (Figure 3)

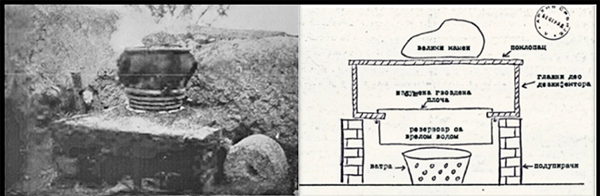

Image 3. Distinguished doctors (left) Official

Military Gazette. (35) No. 16 dated 08.06.1915. p. 328. and (right)

Official Military Gazette. (35) No. 15 dated 04.06.1915. p. 315-6.

Serbian medical services did not emphasize their scientific

contribution. Patriotic and military virtues were valued, and

military awards were received for them. Stammers was also promoted

[26,5], and Serbia honored him. (Figure 2). The great efforts of

Serbian doctors were respected, demonstrating selflessness and

dedication to the Serbian soldier (Figure 3 and 4). Improvements in

the Serbian army followed the same year.

Dr. Hunter also acted as a scientist. He published his contributions

in The Lancet and in a monograph on typhus in Serbia [12]. His

achievements were recognized by the British community, and he was

awarded an honorary doctorate.

Hunter and Subbotić mention the buried stove in their works in its

most primitive initial form, when it did not represent anything

significantly preventive [5:106; 12]. Subbotić points out the

applied teachings of Nikola in the Great War, but not in the

Balkans. They indicate that Nikola's hypothesis needed to be proven

because practice imposed misunderstandings. They sharply point out

problems that were later proven as hypotheses: that the unknown

cause of typhus "is not transmitted only by flea bites," as was then

believed, but that it can also occur through other means, such as

inhalation or contact with "dejecta and vomitus." They mention the

experience of disinfection in hospitals, which is insufficiently

emphasized in the literature about the year 1915. Disinfection was

performed using sulfurization, as was routine in Serbia before the

war, and systematically during the war in Valjevo, according to the

instructions of Hirschfeld, Pecić, and Savić [6]. They present their

observations, which are more interesting to surgeons, regarding the

frequency of typhus complications that require surgical

intervention, such as "parotitis," gangrene, etc.

The authors in 1925 were deeply influenced by emotions for a long

time. In support of this, there is a retrospective in the jubilee

memorial book of 1969, where the prevailing current rationale of the

actors is still presented. Checking the attitudes was as much in

line with major discoveries: the awarding of the Nobel Prize in

1928, or the hypothesis of the existence of late relapse of typhus

in 1934. Also significant was what was written about the same

events, especially before the publication of the memories of 1925:

Hunter's work from 1919 was not considered, nor what Subbotić and

Strongitd published.

There are assessments of the "unenviable position of the medical

service," as well as criticism of the chief's "management of the

medical service," despite Dr. Stanojević only considering it as

"unexplored." It is noted that the public debate began in 1921, and

the question was reopened in 1925 that "our medical experience,

however, remains unexplored to this day" [1:foreword]. The

unexplored nature was directed through the mortality, and therefore,

the culprit for its occurrence was sought...

In the considerations of 1989, the medical historian Dr. Vukšić

clearly expressed disagreement with Dr. V. Stanojević as the editor,

and he explained this. In evaluating Hunter's work, Vukšić did not

differ from Genčić; both emphasized - the success of Hunter's

mission was emphasized. The collaboration between Dr. Hunter and Dr.

Genčić is enough to assess the successful engagement of the Serbian

medical service. But it should be noted that Dr. Nedok proves the

existence of archival material. Based on the documentation found,

which he considered the final report of Dr. Genčić, the suppression

of the epidemic occurred. Therefore, in addition to Dr. Hunter, Dr.

Vukšić, and Dr. Nedok consider the assistance of medical teams that

came to Serbia as crucial. This leaves unaddressed the assessment of

Dr. Hirschfeld, which obviously does not refer to Dr. Subbotić's

"buried stove" because of its modest capacity but rather to the most

significant activity of the Serbian medical service, described by

the words: "Serbian doctors, with superhuman effort, without means

and assistance, began to organize, or rather to improvise devices

for dry disinfection, achieving more than all foreign missions

combined." [27].

If we accept the fair assessment of Dr. Hunter's work and consider

the contribution of the Serbian medical service in proportion to its

involvement, along with the correct attitude of Dr. Genčić as the

leader, then it becomes evident that Serbian doctors deservedly

received the mentioned honors for their patriotic and professional

actions in 1915 (Figures 3,4). This is confirmed by the studies of

Vukšić, Nedok, Zorić, Stanković, Čukić, and others.

Picture 4. Decorated doctors. Official Military

Gazette. (35) No. 15, June 4, 1915, p. 293-4.

The Chief's actions were manifested in several ways as correct:

a) as a physician, he offered a correct solution consisting of

applying Nikolov's teachings, by determining a good strategy for

disinfection, for which he proposed factory-made autoclaves; b) as

the chief, i.e., the leader, he supported all those who offered

arguments that their stance was valid, including doctors (domestic:

Subbotić, Batuta, etc., foreign: Hunter, Morrison, etc.) and the

State Committee for the Suppression of Contagious Diseases, headed

by Eng. Vuković; c) he highlighted proactive individuals (e.g.,

Infantry Major Sretenović); and d) in the Supreme Command, he

founded the Commission for the Suppression of Contagious Diseases,

which made a significant contribution by publishing brochures and

numerous other activities [12]. The contribution of Serbia's medical

service in 1915 was significant for world medicine [28].

Although the list of honorees was not final, among them were: 4

sanitary generals; 12 brigade generals; 13 colonels, who could be or

were the heads of the highest rank, such as sanitary chiefs; then,

senior officers - 4; other distinguished doctors who continued their

careers in civilian life (academics, faculty professors, civilian

sanitary chiefs, ambassadors, physicists, specialists, etc.) - 12.

This group engaged in the suppression of epidemics in 1915 provides

a general assessment that the honored were successful war doctors

who overcame all the wartime trials and were the backbone of

Serbia's medical service.

Dr. Genčić, although "criticized," remained spiritually strong,

considering himself "neither guilty nor obligated" because of his

contributions, for which others were honored with exceptional

recognition [8]. The recipients of the same honor include: Tesla,

Pasteur, Batuta, voivodes. Undoubtedly deserving and recognized, Dr.

Hunter received the same honor (Figure 2), having successfully

collaborated with Dr. Genčić. The highest-ranking honor awarded to

Dr. Genčić in 1929, as the head of the medical service in 1915,

ranks him among successful citizens, about whom their homeland must

care.

CONCLUSION

• There is no foundation found for the assessment by the medical

historian - actors from 1925 that the suppression of the 1915 typhus

epidemic was generally unsuccessful and that the epidemic stopped on

its own, naturally.

• It has been proven that through the work of Dr. Hunter's mission

with the engagement of the Serbian medical service and other foreign

missions, the epidemic was suppressed. Therefore, English and

Serbian doctors rightfully received their honors in 1915.

• Dr. Genčić deserves a reevaluation of the publicly stated

assessment that his work was "criticized." Such an assessment is

scientifically unfounded. There are oversights by critics who did

not give importance to the results of the Serbian medical service,

which are of particular significance to the world of medicine.

• The existing archival material must be studied in more detail.

Whether Dr. Genčić's address to Voivode Putnik on January 15, 1915,

was his last, the reason for it, and Dr. Hirshfeld's assertion, are

separate topics.

LITERATURE:

- Stanojević V, urednik. Istorija srpskog vojnog saniteta,

Naše ratno sanitetsko iskustvo (1925, prvo izdanje), VIC,

Beograd, 1992.

- Vukšić Lj. Istorijski osvrt na prestanak pegavca (Typhus

exanthematicus) 1914-1915. godine u Srbiji, Arhiv za istoriju

zdravstvene kulture Srbije, Beograd, 1989; 1-2, 18:45-57.

- Nedok A. Tri pisma načelnika sanitetskog odelјenja Vrhovne

komande pukovnika Dr Lazara Genčića načelniku štaba iste vojvodi

Putniku o stanju, problemima i radu saniteta operativnih

jedinica i podređenih bolnica tokom ratne 1914. godine (sa

komentarima).800 srpske medicine, Zbornik radova, Beograd: SLD;

2014;13-29.

- Soubbotitch V. A Pandemic of Typhus in Serbia. Proc R Soc

Med. 1918;11(Sect Epidemiol State Med):31-9.

- Hanter V. Epidemije pegavog tifusa i povratne groznice u

Srbiji 1915. godine. (prevodilac: M. Grba), Novi Sad: Prometej;

2016.

- Čukić G. "Ocena" Dr Milana Pecića za suzbijanje epidemije

pegavca u vojnoj zoni Valјeva 1915. godine. 13. naučno-stručni

skup, Arhiv Zaječara, 2022. (Zbornik je u pripremi)

- Čukić G. Nikolovo istraživanje i naši lekari. U: Tokovi,

Berane; 2019(2):27-41.

- Čukić G. Rotacija u srpskom sanitetu 1916. godine. Arhivsko

nasleđe. Arhiv Zaječar. XV (15):89-112.

- ČukićG. Golgotaimedicinskaepopeja 1914/1915. godine ("Specijalnaepidemiologijapegavca"

između 1909. i 1919. godine). Timočki medicinski glasnik. 2007;

4 (32):194-204.

- Čukić G. Defetizam u epidemiji pegavca 1915. godine i

njegovo rušenje. U: 800 godina srpske medicine, Novopazarski

zbornik 2019. Beograd; 2020;581-604.

- Kaper S. O Crnoj Gori. Podgorica; 1999.

- Čukić G. Srpska prevencija pegavca 1915. godine. Zaječar

2018.

- Srpsko lekarsko društvo, Spomenica 1872-1972, Beograd :

Srpsko lekarsko društvo. 1972.

- Protić Đ. „Srpsko bure“. Vojno-sanitetski glasnik.

1933;(4):198-205.

- Grba M. Nastanak, širenje i suzbijanje epidemija tifusa u

Srbiji 1914-1915. U: Hanter V. Epidemije pegavog tifusa i

povratne groznice u Srbiji 1915. godine. (prevodilac: M. Grba),

Novi Sad: Prometej. 2016;11-79.

- Serbian Orders of the Royal Army Medical Corps Mission to

Serbia. The Order of St. Sava, British Medical Journal, War

notes, May 20, 1916.

- Borjanović S. Epidemiološka studija pegavca u Srbiji i

mogućnost njegove eradikacije (doktorska disertacija). Beograd:

Medicinski fakultet. 1977.

- Čukić G. Čemu nas uči prošlost pegavog tifusa. Berane:

Centar za kulturu Berana; 2016.

- Todorović K, Žarković B. Akutne infektivne bolesti sa

epidemiologijom. Beograd: Institut za stručno usavršavanje i

specijalizaciju zdravstvenih radnika, 6. izdanje. Beograd; 1972.

- Čukić G. Epidemija pegavog tifusa u Topčiderskom kaznenom

zavodu 1906/7. godine. U: Zbornik radova sa XII naučno-stručnog

skupa Istorija medicine, farmacije, veterine i narodna

zdravstvena kultura, održanog 2021. Knj. 11. Zaječar;

2022;45-66.

- Spomen knjiga Zavoda za zdravstvenu zaštitu SR Srbije. 50

godina higijenske službe i socilanomedicinske službe i 120

godina preventine medicine u Srbiji, Beograd: Zavod za

zdravstvenu zaštitu SR Srbije; 1969.

- Uprava državne statistike. Statistički godišnjak Kralјevine

Srbije, 1907., 1908. Beograd, 1913.

- Čukić G. Narodni nazivi za tifuse na području Toplice (Imenovanje

– „tifusa“). U: Zbornik radova sa XI naučno-stručnog skupa

Istorija medicine, farmacije, veterine i narodna zdravstvena

kultura, održanog 2019. Knj. 10. Zaječar; 2021;191-217.

- Subbotić V. O pegavom tifusu u Srbiji. Međusaveznička

sanitarna konferencija u Parizu 15.03.1916. Muzej nauke i

tehnike, Zbirka Muzeja srpske medicine Srpskog lekarskog društva,

(MNT.T:11.7.1546) Ministarstvo vojno, Sanitetsko odelјenje, Pov.

br. 1625, 25.04 1916., Krf, Muzej SLD, Beograd.

- Antić D. Pegavi tifus u kragujevačkoj Prvoj rezervnoj vojnoj

bolnici. U: Stanojević V. Istorija srpskog vojnog saniteta, Naše

ratno sanitetsko iskustvo (original 1925). Beograd: VIC. 1992;

314-28.

- Rid Dž. Rat u Srbiji 1915. Cetinje; 1975.

- Hiršfeld L. Istorija jednog života. Beograd: Srpska

književna zadruga (knj. 377). 1962;56-7.

- Čukić G. Doprinos srpskog saniteta medicini sveta 1914/15.

godine. Glasnik javnog zdravlјa. 2023;97(2):233-49.

|

|

|

|