| |

|

|

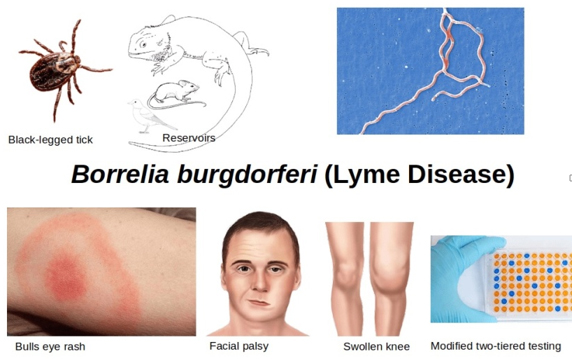

DEFINITION AND EPIDEMIOLOGY OF LYME DISEASE Lyme disease

(LD), or MORBUS LYME, is a chronic multisystem infectious disease in

humans, transmitted through the bite of an infected hard tick,

Ixodes ricinus, carrying one of the bacteria such as Borrelia

burgdorferi (Bb) (Figure 1), and less commonly other Borrelia

species: Borrelia garinii (Bg) and Borrelia afzelii (Ba).

It is a multisystem disease that can affect the skin, joints, heart,

and nervous system. Lyme disease is particularly known for its

frequent manifestation as the characteristic “erythema migrans”, a

bull’s-eye-shaped skin rash [1].

Figure 1. Borrelia burgdorferi magnified 400 x

Source:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f3/Borrelia_burgdorferi_%28CDC-PHIL_-6631%29_lores.jpg

When discussing the developmental stages of ticks, the starting

point is the egg, which the female (adult) lays in early spring.

From these eggs, larvae hatch in early summer. The larva takes its

first blood meal from the nearest available animal—most often

micromammals (forest and field rodents, hedgehogs, and others).

Humans can also occasionally be bitten by larvae, although this

occurs much less frequently compared to other developmental stages

of the tick.

After feeding, the larva molts (matures) into a nymph, which then

takes a second blood meal from the nearest host. For nymphs, these

hosts typically include hares, birds, deer, and occasionally humans

who spend time in tick habitats. Borrelia is transmitted through

tick saliva during feeding, usually after 48 hours or longer.

There are three theories regarding the transmission of Borrelia

burgdorferi (Bb) from the tick to the next host, with two being most

widely accepted. The first suggests that during the tick’s intense

blood-feeding phase, once it becomes engorged, it regurgitates part

of its intestinal contents (Bb resides in the tick’s midgut). The

second, less common but still recognized in the literature [1,2],

proposes that Bb migrates from the midgut to the salivary glands.

This theory implies a transmission mechanism similar to that of

mosquitoes transmitting Plasmodium. Advocates of this theory often

recommend prophylactic antibiotic treatment after every tick bite,

which is incorrect.

Experimental studies on the transmission of Borrelia from infected

ticks to mice have shown that infection rarely occurs within the

first 24 hours of tick attachment. The likelihood of infection

increases with the tick’s duration of attachment—particularly after

48 hours, and especially after 72 hours. Therefore, information

about the tick’s attachment time (less than 24 hours) is extremely

important for the prevention of Lyme disease. Prompt and proper

removal of the tick within the first few hours can be crucial,

especially if the tick is infected with Bb [3].

In Lyme disease, the reservoir represents the ecological niche—the

place within the host (tick, small rodent, etc.) where the pathogen

lives, persists as a species, and/or reproduces, usually without

harming its host.

In the case of Lyme disease, the tick can serve both as a reservoir

of Bb and as the source of infection (the one that directly

transmits Bb to a new host). Once infected, a tick can transmit Bb

throughout all its developmental stages—from larva to adult—and even

transovarially (from female to offspring). The vector, or carrier of

the pathogen, is Ixodes ricinus (Europe), Ixodes pacificus and

Ixodes scapularis (America), Ixodes persulcatus (Asia), etc., while

the causative agent belongs to the Borrelia burgdorferi genospecies

[4,5].

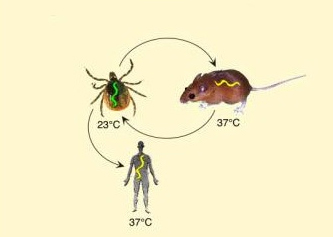

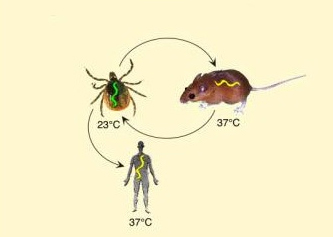

The term “Borrelia cycle” is translated as either the life cycle of

Borrelia or the enzootic cycle of Borrelia in English. It refers to

the complex life cycle of the Lyme disease bacterium (Borrelia

burgdorferi), which alternates between tick vectors and vertebrate

hosts. This enzootic cycle involves the transmission of the

bacterium from an infected tick to a host, and potentially back to

another tick (Figure 2) [6].

Figure 2. life cycle (transmission cycle) of

Borrelia, which alternates between the tick vector and the

vertebrate host.

Source:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/08/Borrelia_cycle.jpg

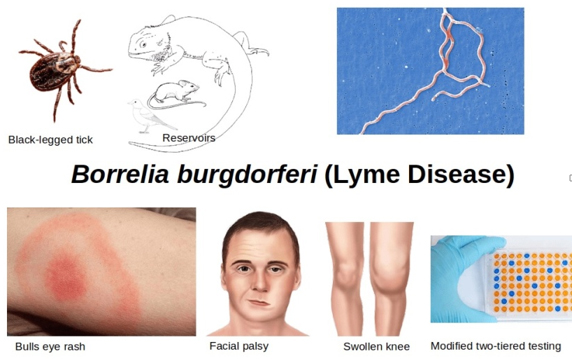

CLINICAL ASPECTS OF LYME DISEASE

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne infectious disease

in Europe and North America. LD is typically a seasonal illness,

occurring during periods of tick activity—from early spring and the

first warm days (nymphal stage), throughout June (larval and nymphal

stages), and up to the late autumn months (adult stage). During the

rest of the year, when tick activity ceases, Lyme disease does not

occur.

When searching for a diagnosis in patients presenting with symptoms

suggestive of LD, serological testing is most commonly used to raise

clinical suspicion. The incubation period ranges from 3 to 30 days,

from the tick bite to the appearance of signs and symptoms of Lyme

disease. It is important to note that not every erythema at the site

of a tick bite is Erythema migrans (EM). EM occurs in 60–80% of

cases and is often accompanied by flu-like symptoms.

At the site of the tick bite, within 5–7 days or longer, a

characteristic skin lesion may appear—Erythema migrans—which begins

as a macule or papule and can enlarge to as much as 50 cm in

diameter. EM presents as redness expanding from the bite site toward

the periphery in the form of irregular concentric rings with

serrated, more intensely red edges. The redness is flat, warm to the

touch (like surrounding skin), and does not cause pain or itching

[7,8,9].

This characteristic skin lesion—EM—is a hallmark sign of Lyme

disease. It differs from other skin rashes because it lacks tumor

(swelling) and dolor (pain), and the calor (warmth) is the same as

in surrounding skin [10]. Alongside the lesion (EM), early

symptoms—often flu-like—may include headache, mild fever (rare),

chills, shivering (rare), muscle and joint pain, lymphadenopathy,

and fatigue, which is profound, persistent, and unrelated to

physical activity [10,11]. Symptoms typically last around four weeks

[11].

In untreated patients, after several weeks, hematogenous

dissemination can occur, leading to systemic manifestations such as

fatigue, myalgia, and skin, cardiac, and neurological disorders

[10,11]. Arthritis develops in about 60% of patients, usually

monoarticular or oligoarticular, predominantly affecting the knee

joint—a sign of late-stage LD (third stage) [10,12].

Neurological manifestations occur in about 10–20% of patients, most

commonly facial nerve palsy. This belongs to the secondary stage and

is less common in Europe. The Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) identifies this symptom as frequent in the United

States [12].

The second stage may also include carditis, occurring in

approximately 8% of untreated, infected individuals, presenting with

palpitations and atrioventricular (AV) conduction abnormalities, as

well as electrocardiographic changes in the S-T segment and T wave

[10,12].

The late stage, developing months or even years after untreated Lyme

disease, leads to polyarthritis and chronic skin lesions with

discoloration, known as acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans [11,13].

Figure 3. Borrelia Burgdorferi - Lyme disease

Source:

https://i0.wp.com/microbeonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Borrelia-Burgdorferi-Lyme-Disease-min.png?ssl=1

Prolonged attachment of a tick to the skin increases the

likelihood of transmitting Borrelia burgdorferi. Therefore, timely

removal of the tick is crucial for reducing the risk of infection.

The longer the tick remains attached, the higher the probability of

pathogen transmission. For this reason, prompt and proper tick

removal is one of the most important steps in preventing the

clinical manifestation of Lyme disease [14,15].

If a tick is observed on the body, it is recommended to remove it as

soon as possible [16,17]. Ideally, this should be done in a

healthcare facility, where a physician can assess the risk of

infection and determine further management. If immediate

professional removal is not possible, the tick can be removed

independently using fine-tipped tweezers. The tweezers should grasp

the tick as close to the skin as possible, near its head, and pull

it out slowly, steadily, and evenly without sudden movements (Figure

4).

After removal, the bite site should be disinfected with alcohol or

iodine [18]. Regardless of successful removal, it is recommended to

see a physician promptly to evaluate the risk, monitor for potential

symptoms, and decide whether further diagnostic or prophylactic

measures are needed [17,19]. The key is not only proper tick removal

but also monitoring one’s health and seeking medical attention, as

infection can occur even after the tick has been removed [16,17].

Figure 4. Removing ticks with tweezers

Source: https://www.bbc.com/serbian/lat/svet-69247310

Routine testing of ticks themselves for the presence of Borrelia

burgdorferi or other pathogens is not recommended for clinical

purposes, as a positive result does not confirm that infection has

been transmitted, nor does it determine therapeutic management. The

main criteria for deciding on prophylactic treatment include: the

tick species (Ixodes), endemic region, duration of attachment (>36

hours), and time since removal (<72 hours)—as recommended by the

IDSA/AAN/ACR Lyme disease guidelines (2020) [20].

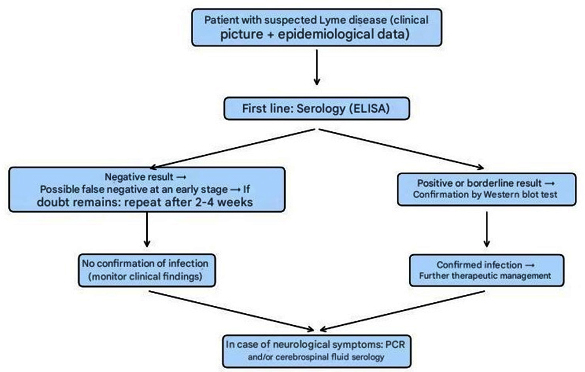

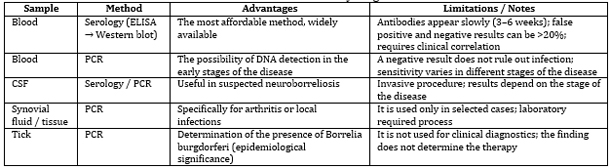

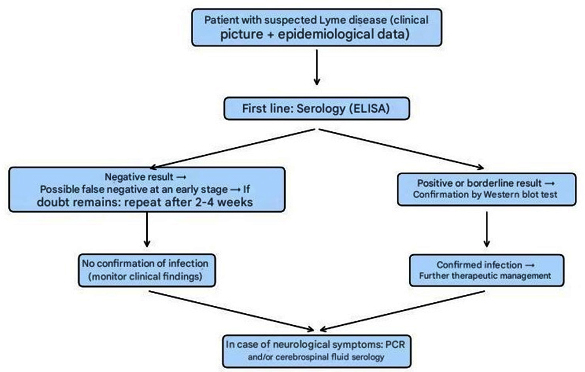

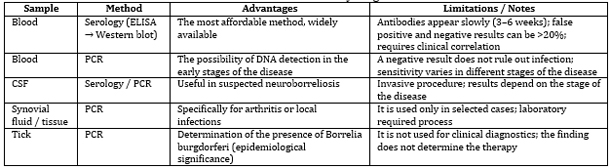

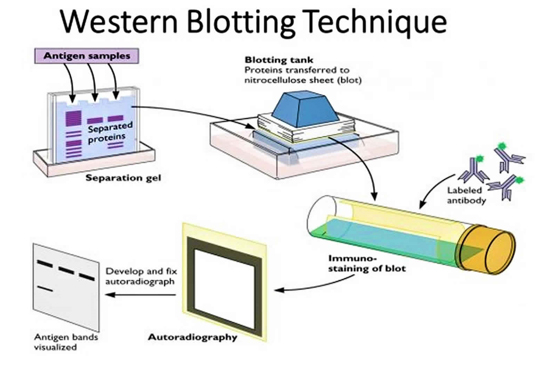

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS OF LYME DISEASE

The laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease involves a combination

of methods applied according to the stage of the disease and its

clinical presentation [21,22]. The most accessible and widely used

diagnostic approach is serological testing of blood samples (ELISA,

confirmed by Western blot) [21,23]. In cases where neuroborreliosis

is suspected, both serological testing and PCR analysis of

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are performed [22,24].

The PCR method enables the direct detection of Borrelia burgdorferi

DNA in blood, CSF, or specific tissue samples; however, a negative

result does not exclude infection. Although removed ticks can also

be tested by PCR for pathogen detection, such testing has

epidemiological significance only and does not guide therapeutic

decisions [21,25].

Proper interpretation of laboratory findings requires integration of

test results with the clinical picture and epidemiological factors,

since serological tests may yield false-positive or false-negative

results, particularly in the early stages of the disease.

Algorithm of laboratory diagnosis of Lyme

disease

Table 1. Laboratory diagnostics

Ticks are not used for serological diagnosis in clinical

practice. Their testing serves exclusively epidemiological purposes

or research on the distribution of pathogens. Serological tests of

blood and cerebrospinal fluid remain the cornerstone of routine

laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease.

Serological testing is the most accessible diagnostic approach

(performed by almost all public health institutes) and represents

the first step in the serological diagnosis of Lyme disease.

However, these tests are neither highly specific nor highly

sensitive, yielding more than 20% false-positive and false-negative

results. It is also important to emphasize that antibodies to

Borrelia burgdorferi develop slowly, and blood sampling should not

be performed before the end of the third or fourth week after the

onset of symptoms. Therefore, caution is required when interpreting

serological results in Lyme disease.

The main serological tests used for diagnosis are ELISA and

immunofluorescence assays (IFA). The ELISA test (Figure 5) for

Borrelia burgdorferi identifies the presence of IgM and IgG

antibodies, indicating whether it is an acute infection (IgM) or a

past infection (IgG)—although it is important to note that the

presence of IgG antibodies in Lyme disease does not always confirm a

past infection, as it might in other diseases [26,15].

IgM antibodies usually appear 2–4 weeks after the onset of the

erythema migrans lesion but are not always detectable at sufficient

levels for serological identification and typically disappear after

4–6 months. In some cases, IgM antibodies may persist for several

months after initial detection. IgG antibodies typically appear 8–12

weeks after the onset of illness and reach their peak within 4–6

months.

In the serological diagnosis of Lyme disease, the initial tests

include ELISA, EIA (enzyme immunoassay), or IFA (immunofluorescence

antibody assay). Negative results in the early phase of the disease

do not exclude the diagnosis, as antibodies may still be

insufficiently developed—particularly if antibiotic therapy was

initiated early or if erythema migrans is still present. Positive or

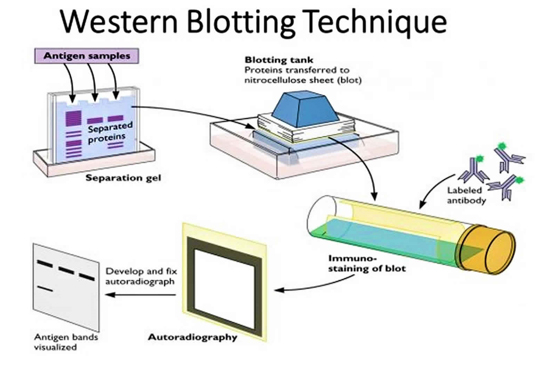

borderline results should be confirmed using the Western immunoblot

test (Figure 6).

If serological results are negative, but clinical symptoms of Lyme

disease persist, it is recommended to repeat testing after 2–4 weeks

[27,28].

Figure 5. How to choose the right propeller kit

Figure 6. Western blotting technique, used to

detect specific proteins in samples

Source: https://www.bmgrp.com/ Source: https://healthjade.net/western-blot/

how-to-choose-the-right-elisa-kit/

In addition to these tests, PCR is less commonly used in

diagnostics and is recommended for testing the tick itself for the

presence of Lyme disease pathogens (primarily for research purposes,

not routine diagnostics). PCR is also the only method used in

everyday diagnostics, apart from the cultivation of Borrelia on BSK

II medium, which is performed only in research settings.

False-positive serological results for Lyme disease can occur in

patients with syphilis. Early diagnosis and timely administration of

antimicrobial therapy play a key role in preventing cardiac,

neurological, and musculoskeletal complications. It is important to

note that antibiotics in the initial stage of Lyme disease do not

prevent the development of symptoms in later stages but serve as

prophylactic treatment to reduce the risk of disease progression.

TREATMENT OF LYME DISEASE

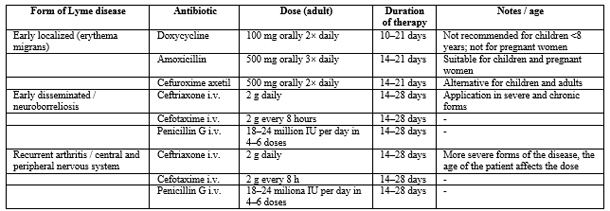

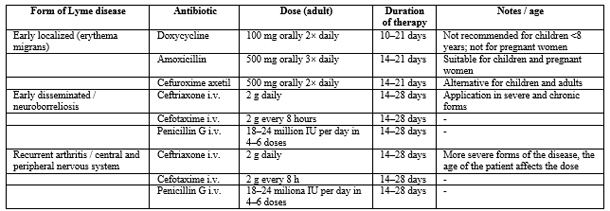

In the treatment of early Lyme disease, oral antibiotics such as

amoxicillin, doxycycline, or cefuroxime are used. The choice of

antibiotic and duration of therapy depend on the patient’s age and

the clinical stage of the disease. Doxycycline is generally avoided

in children under 8 years due to potential effects on teeth and

bones, while amoxicillin is preferred in pregnant women.

For patients with recurrent arthritis or involvement of the central

or peripheral nervous system, parenteral therapy with intravenous

antibiotics—most commonly ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, or penicillin

G—is administered. IV therapy is reserved for severe or chronic

forms of the disease, with dose, duration, and patient age being

crucial factors for treatment effectiveness and complication

prevention.

Lyme disease therapy is guided by the clinical form, disease

severity, and patient age. In early localized forms, oral

antibiotics—doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime—are prescribed,

with restrictions for children under 8 years and pregnant women.

Treatment duration ranges from 10 to 21 days, depending on the

antibiotic and clinical presentation. For more severe or chronic

forms, including neuroborreliosis and recurrent arthritis,

parenteral therapy with intravenous ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, or

penicillin G is used, typically for 14–28 days. Treatment efficacy

depends on timely administration, appropriate dosage, therapy

duration, and patient age. [29,30].

Table 2. Lyme Disease Therapy: Antibiotics,

Dosages, and Duration

Notes: Doxycycline is not used in children under 8 years of age

and in pregnant women due to the risk to teeth and bones. Oral

therapy is applied in early localized forms. I.V. therapy is used in

severe, disseminated, or chronic forms, in cases of neuroborreliosis

and recurrent arthritis. The duration of therapy can be adjusted

according to the patient’s clinical response.

PREVENTION

Control of ticks in areas frequently visited by people (parks,

forested parks, recreational areas) represents a fundamental measure

for preventing tick bites and, consequently, reducing the risk of

Lyme disease transmission. Preventive activities can be divided into

ecological control measures, personal protective measures, and

public health interventions:

Ecological control measures include the application of appropriate

acaricides on limited areas with high tick populations, mowing and

maintenance of grassy areas—especially in places used for recreation

and play—removal of leaves, low vegetation, and branches in parks

and yards to reduce suitable tick habitats, control of rodent

populations that are natural reservoirs of Borrelia burgdorferi, and

minimizing human-rodent contact.

Personal protective measures involve wearing appropriate clothing

when in nature: long sleeves, long pants tucked into socks, closed

shoes, and light-colored clothing to facilitate tick detection;

using repellents based on DEET, icaridin, or permethrin (on

clothing), especially for individuals spending extended time

outdoors in endemic areas; and performing a full-body tick check

after outdoor activities, including hair, skin folds, and areas

where ticks commonly attach.

Public health interventions include educating the population about

the risks of tick bites, protection methods, and the importance of

early tick removal; organizing tick control campaigns in public

areas during peak activity seasons (spring and summer); monitoring

and surveillance of tick populations in endemic regions; and risk

mapping for the local population. [31-33].

CONCLUSION

Lyme disease represents a significant public health problem in

endemic areas of Europe and North America. Prevention is based on

reducing contact with ticks, wearing protective clothing, using

repellents, and implementing ecological measures to control tick and

rodent populations. Diagnosis is primarily clinical, supported by

serological testing, while molecular methods serve as supplementary

diagnostic tools. Timely and appropriate antibiotic therapy in the

early stage of the disease is crucial for preventing systemic

complications. Educating the public and healthcare personnel, as

well as proper tick removal, are the most effective strategies for

controlling and preventing Lyme disease.

LITERATURE:

- Connie R. Mahon I Donald C. Lehman TEXTBOOK OF DIAGNOSTIC

MICROBIOLOGY.ELSEVIER. 2019.

- Savić B, Mitrović S, Jovanović T. MEDICINSKA MIKROBIOLOGIJA.

Medicinski fakultet Beograd. 2022.

- Nikolić S., Stojanović D. INFEKTIVNE BOLESTI SA

EPIDEMIOLOGIJOM – priručnik za zdravstvene radnike, Nota,

Knjaževac, 1998 (ISBN 86.357.0437.1).

- Barbour, A. G., and G. R. Johnson. 1988. "The Borrelia

burgdorferi sensu lato: the Lyme disease spirochete." Annual

Review of Microbiology 42: 345-372.

- Stanek, G., et al. 2011. "Lyme borreliosis." The Lancet

379(9714): 461-473.

- Estrada-Peña A, de la Fuente J. The ecology of ticks and

epidemiology of tick-borne viral diseases. Antiviral Res.

2014;108:104-128. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.05.016.

- Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis.

Lancet. 2012;379(9814):461-473.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60103-7.

- Steere AC, Strle F, Wormser GP, Hu LT, Branda JA, Hovius JW,

et al. Lyme borreliosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16090.

doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.90.

- Rizzoli A, Hauffe HC, Carpi G, Vourc’h GI, Neteler M, Rosa

R. Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2011;16(27):19906.

- Steere AC, Strle F, Wormser GP, Hu LT, Branda JA, Hovius JW,

et al. Lyme borreliosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16090.

doi:10.1038/nrdp.2016.90.

- Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis.

Lancet. 2012;379(9814):461-473.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60103-7.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Lyme

Disease [Internet]. CDC; 2023. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme

- Hu LT. Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med.

2016;164(9):ITC65-ITC80. doi:10.7326/AITC201605030

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Lyme

Disease: Transmission [Internet]. Atlanta: CDC; 2024 [cited 2025

Oct 1]. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/causes/index.html

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Factsheet about Lyme borreliosis [Internet]. Stockholm: ECDC;

2025 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from:

https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/lyme-borreliosis/facts

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tick

Removal and Testing [Internet]. CDC; 2023. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/removing_a_tick.html

- Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis–from tick bite to

diagnosis and treatment. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2018;42(3):233-258.

doi:10.1093/femsre/fux047.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Vector-borne diseases –

Ticks [Internet]. WHO; 2022. Available from:

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, Halperin JJ, Steere

AC, Klempner MS, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and

prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and

babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious

Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis.

2006;43(9):1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667.

- Lantos PM, Rumbaugh J, Bockenstedt LK, Falck-Ytter YT,

Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Auwaerter PG, et al. Clinical Practice

Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA),

American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of

Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention,

Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis.

2021;72(1):e1-e48.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Lyme

Disease: Laboratory Testing [Internet]. CDC; 2023. Available

from:

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/diagnosistesting/labtest/twostep/index.html

- Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis–from tick bite to

diagnosis and treatment. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2018;42(3):233-258.

doi:10.1093/femsre/fux047.

- Hu LT. Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med.

2016;164(9):ITC65-ITC80. doi:10.7326/AITC201605030.

- Mygland Å, Ljøstad U, Fingerle V, Rupprecht T, Schmutzhard

E, Steiner I. EFNS guidelines on the diagnosis and management of

European Lyme neuroborreliosis. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(1):8-16.

doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02862.x.

- Dessau RB, van Dam AP, Fingerle V, Gray J, Hunfeld KP,

Jaulhac B, et al. To test or not to test? Laboratory support for

the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis: a position paper of ESGBOR,

ESCMID Study Group for Lyme Borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Infect.

2018;24(2):118-124. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.08.025.

- Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Academy of

Neurology; American College of Rheumatology. Guidelines for the

Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect

Dis. 2020;72(1):e1-e48. OUP Academic

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Factsheet about Borreliosis (Lyme disease) [Internet].

Stockholm: ECDC; 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from:

https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/borreliosis/facts/factsheet

Evropski centar za prevenciju bolesti

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clinical

Care of Lyme Disease [Internet]. Atlanta: CDC; 2024 [cited 2025

Oct 1]. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/hcp/clinical-care/index.html cdc.gov

- Lantos PM, et al. 2020 guidelines for the prevention,

diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme disease. Arthritis Care Res

(Hoboken). 2021 Jan;73(1):1-9. doi: 10.1002/acr.24495.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Lyme

disease treatment. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/treatment/index.html

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Personal protective measures against tick bites. Available from:

https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/disease-vectors/prevention-and-control/protective-measures-ticks

- National Park Service (NPS). Ticks and tickborne diseases.

Available from:

https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/ticks-and-tickborne-diseases.htm

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

(NIOSH). Tickborne diseases in workers. Available from:

https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/outdoor-workers/about/tick-borne-diseases.html

|

|

|

|