|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [

Contents

] [ INDEX ]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Original paper THE ROLE OF CLINICAL AND LABORATORY PARAMETERS IN RISK ASSESSMENT OF PATIENTS WITH CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES Marko Marković (1), Jelena Gotić (1), Jovana Radovanović (2) (1) PRIMARY HEALTHCARE CENTER PIROT, PIROT; (2) FACULTY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF KRAGUJEVAC, KRAGUJEVAC |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Download in pdf format | SUMMARY:

Introduction: Cardiovascular and metabolic diseases represent a

significant challenge in modern healthcare due to their high

mortality rates and impact on quality of life. Accurate risk

assessment is essential for therapy personalization and the

prevention of complications, encompassing clinical, inflammatory,

and hemostatic risk factors. The aim of this study was to

investigate the role of clinical and laboratory parameters in risk

assessment among patients with cardiovascular diseases, with a

particular focus on inflammatory and hemostatic indices such as the

Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Mean Platelet Volume (MPV), and

the Red Cell Distribution Width to Platelet Ratio (RPR). Subjects

and Methods: The study included 311 patients with cardiovascular

diseases. Retrospective and prospective methods were used to collect

clinical and laboratory data, including body mass index, blood

pressure, and lipid profile. Statistical analysis comprised factor

analysis and multiple linear regression. Results: The study

demonstrated that clinical and laboratory parameters, including LDL

cholesterol, as well as inflammatory-hemostatic indices such as MPV

and RPR, were significantly associated with the presence and

combinations of cardiovascular diseases. The RPR index was highest

in patients with hypertension and stents (p < 0.001), indicating

increased procoagulability and inflammatory status in these groups.

Factor analysis identified three main factors, of which the age-hematological

factor was the only one showing a statistically significant

association with cardiovascular diseases (p = 0.008), confirming its

predictive value. Conclusion: These findings suggest that the

integration of clinical and laboratory indicators, with a particular

emphasis on inflammatory-hemostatic indices and age-hematological

variables, allows for earlier identification of high-risk patients

and provides a foundation for the development of personalized

therapeutic strategies. Keywords: clinical parameters, laboratory parameters, cardiovascular diseases |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

INTRODUCTION Cardiovascular (CVD), as well as metabolic diseases, represent one of the most significant challenges in modern healthcare, due to their high mortality rates and severe impact on patients’ quality of life. These conditions encompass a wide range of disorders, including coronary artery disease (CAD), arterial hypertension (HTN), and dyslipidemia (DLD), which often coexist and influence each other [1]. According to the World Health Organization, cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death globally, further emphasizing the need for effective prevention and treatment strategies [2]. Cardiometabolic syndrome represents a contemporary epidemic that can predict overall and cardiovascular mortality, the incidence and progression of coronary and carotid atherosclerosis, as well as sudden death, independently of other cardiovascular risk factors [3]. A significant increase has recently been observed in the incidence of comorbidities between metabolic disorders and cardiovascular diseases, particularly in populations at risk for metabolic syndrome or pre-metabolic syndrome [4]. Individuals with metabolic syndrome (MetS) have a threefold higher relative risk of myocardial infarction or stroke, a twofold higher risk of CVD or death from such events, and a fivefold higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in both sexes compared to those without the syndrome [5–7]. Research indicates that nearly half of patients with coronary artery disease meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome [5,7,8]. One study demonstrated a clear association between cumulative exposure to metabolic disorders and myocardial infarction, highlighting the importance of managing metabolic disorders for CVD prevention [9]. Another study revealed a positive correlation between cumulative metabolic burdens and the risk of developing atrial fibrillation (AF) [10]. Promoting an active lifestyle can improve metabolic disorders in some patients and aid in blood pressure control [11]. Both individual components of MetS and MetS as a whole increase the risk of heart failure (HF) and ischemic stroke [12]. Reverse causation factors could not be adequately accounted for in observational studies, and therefore the causal relationship between metabolic disorders and various CVDs remains uncertain [13]. The importance of risk assessment in patients with cardiovascular and metabolic disorders lies in the ability to identify high-risk individuals, allowing timely intervention and tailored therapeutic strategies. Risk stratification using SCORE-2 (Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation) enables the estimation of 10-year risk for cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction and stroke. This tool takes into account factors including age, sex, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, smoking status, and the presence of diabetes. In modern medical practice, risk assessment using SCORE-2 and SCORE2-OP for older patients [14,15] represents an essential component of clinical decision-making. This approach facilitates the development of individualized therapy and prevention plans, thereby significantly reducing the overall risk of serious cardiovascular events. The use of this tool allows for more accurate identification of high-risk patients and the implementation of appropriate interventions, contributing to improved health outcomes. As noted, risk assessment in patients with cardiovascular and

metabolic diseases constitutes a fundamental aspect of contemporary

clinical medicine, given the prevalence of these conditions and

their significant contribution to morbidity and mortality worldwide.

Cardiovascular diseases, including ischemic heart disease and

cerebrovascular disorders, are frequently associated with metabolic

disturbances such as diabetes mellitus (DM) and metabolic syndrome (MetS).

This association is reflected in shared pathophysiological

mechanisms, which further complicates diagnosis and management.

Clinical parameters, including—but not limited to—blood pressure,

lipid profile, blood glucose levels, body mass index (BMI), and

inflammatory markers, serve as the basis for risk stratification and

the personalization of therapeutic strategies [16]. Age is the strongest non-modifiable risk factor for CVD. The increase in cardiovascular risk is continuous and progressive in both men and women. However, the transition to the high-risk category for the development of cardiovascular disease appears to occur at specific ages for each sex [17]. Considering a risk estimated at over 20% for 10 years for the composite outcome of myocardial infarction, stroke, and all-cause mortality, the transition to high risk occurred at 48 years for men and 54 years for women. When the broader definition of CVD included revascularization, the age of transition decreased to 41 and 48 years for men and women, respectively. The transition from low to moderate risk occurred at 35 and 45 years for men and women, respectively, according to the broader definition [17]. In the general population, the incidence of myocardial infarction is higher in men than in women, with age-adjusted risk coefficients [17]. A study by Cai et al., which included 10 observational studies with a total of 166,027 patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), concluded that among these patients, the relative risk of mortality was 5.09; for coronary artery disease 9.38; myocardial infarction 6.37; atrial fibrillation 1.36; and stroke 4.08. This further indicated that the relatively increased risk for CAD, CVD, myocardial infarction, and stroke was higher in women with T1DM [18]. Thus, women with type 1 diabetes have a 50% higher relative risk for fatal coronary events compared to men. This phenomenon may be partly explained by a less favorable cardiovascular risk profile in women, associated with hypertension (HTN) and hyperlipidemia. It is also important to consider whether hormonal changes during menopause further contribute to this increased risk, given that decreased estrogen levels may negatively affect women’s cardiovascular health. Hypertension (HTN) is a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and stroke-related mortality. Isolated systolic hypertension is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD) across all age groups and in both men and women [19,20]. LDL cholesterol is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Data from the supplementary observational MRFIT study [21], conducted in the pre-statin era, showed that among 342,815 middle-aged men in the United States (of whom 5,163 had diabetes mellitus, DM) followed for 16 years, the absolute adjusted risk of death from CVD, stratified by LDL cholesterol level, was significantly higher in patients with DM. Specifically, the risk of cardiovascular mortality was between 2.83 and 4.46 times higher in patients with DM compared to those without DM, highlighting the importance of LDL stratification as a key risk factor in this population [34]. LDL cholesterol is commonly stratified into the following categories: optimal (<100 mg/dL), near optimal (100–129 mg/dL), borderline high (130–159 mg/dL), high (160–189 mg/dL), and very high (≥190 mg/dL). Patients with DM often present with elevated LDL cholesterol levels, further increasing their risk for developing cardiovascular disease. Regular monitoring and management of LDL cholesterol in these patients are recommended to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events. The MRFIT study [21] also demonstrated that the increase in CVD mortality was disproportionately higher in patients with DM, suggesting that cholesterol is a strong and independent risk factor for CVD mortality, potentiated by DM. However, the question arises: which is the stronger risk factor—DM or LDL cholesterol? While both factors play a significant role, research suggests that DM may exert a stronger influence on cardiovascular outcomes, particularly when considering additional factors such as inflammation and metabolic disturbances present in patients with DM [35]. According to Zhang et al., chronic low-grade inflammation of the vascular intima in patients with type 2 diabetes further increases the risk of CVD, while Chen et al. highlighted that GLP-1 agonists significantly reduce cardiovascular events in this population, suggesting that DM has a stronger impact on cardiovascular outcomes [35,36]. Considering LDL reduction with statins, the study by Hodkinson et al. showed that lowering LDL by 1 mmol/L with a statin reduces relative CVD risk by one-fifth. The study also indicates that this linear phenomenon can occur similarly at any baseline LDL level, at least down to 1.293 mmol/L (50 mg/dL) [22]. In patients with DM, statins promote a proportional reduction of 9% in all-cause mortality (p=0.02) and 21% in major vascular events (p<0.0001) per mmol/L reduction in LDL-C. Additionally, there is a significant reduction in acute myocardial infarction (p<0.0001), coronary revascularization (p<0.0001), and stroke (p<0.0002). The aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between clinical and laboratory parameters, with a particular focus on inflammatory-hemostatic indices, in predicting cardiovascular risk. This work also seeks to identify key factors that may facilitate the early recognition of high-risk patients, enabling timely intervention and tailored therapy. MATERIAL AND METHODS This research was conducted as a combined retrospective-prospective, cross-sectional, longitudinal cohort study at the Pirot Health Center, during the period from January 1, 2024, to June 1, 2024. In the retrospective part, patients’ electronic health records were analyzed to collect data on demographic characteristics, smoking status, pharmacotherapy over the previous six months, and laboratory results not older than six months. In the prospective part, new data on anthropometric measurements and blood pressure values were systematically collected during each patient visit. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Pirot Health Center, Pirot (reference number: 02-15/EO). The study included 311 patients over 40 years of age with previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and/or cardiovascular diseases (coronary artery disease, arterial hypertension, angina pectoris, atrial fibrillation, or implanted stent). All patients had diabetes for more than five years, ensuring the relevance of the results. Exclusion criteria included patients with malignancies, chronic kidney disease, acute infections, pregnant women, and those who had undergone therapy changes within the last six months. All participants provided written informed consent. The control group consisted of patients with T2DM without clinically or instrumentally confirmed cardiovascular events (n=52), serving as a reference subgroup for comparison with other cohorts. For each patient who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study, data were collected from electronic health records regarding age, sex, smoking status, and laboratory parameters not older than six months, including: Hematological parameters: total leukocyte count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets. Biochemical parameters: glucose, glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c),

total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C),

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides, urea,

and creatinine. Inflammatory markers: inflammation was assessed

through the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), red cell

distribution width to platelet count ratio (RPR), and mean platelet

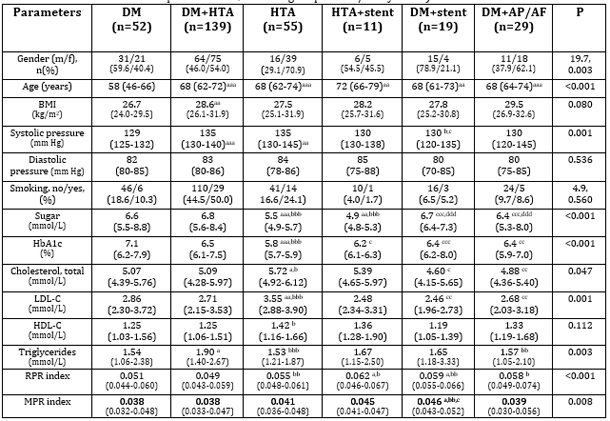

volume to platelet ratio (MPR). In the methodology, the parameters listed in Table 1 were used to evaluate different combinations of cardiovascular diseases and metabolic disorders. Key demographic (sex – percentage of men and women in different groups; age – mean age of patients in each group), clinical (BMI – body mass index for each group; blood pressure – systolic and diastolic values in different patient groups; smoking – percentage of smokers), and biochemical parameters (glucose and HbA1c – mean values for patients with diabetes, hypertension, and their combinations; total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C – mean values for different groups; triglycerides – mean values) were analyzed for their potential significance in risk stratification. It is important to emphasize the p-values indicating statistically significant differences between groups, as shown in the last column (“p”). These values are essential for understanding differences among patient groups with various metabolic disorders and cardiovascular diseases. RESULTS Table 1. Baseline clinical and biochemical data of patients with various metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, as well as their combinations (DM, HTN, DM+HTN, HTN + implanted stent, DM + implanted stent, DM + angina pectoris/arrhythmia)

A higher proportion of women was observed in the groups of patients with hypertension (HTN) and the combination of diabetes (DM) and hypertension, as well as in the group with diabetes and angina pectoris/AF. The youngest group consisted of patients diagnosed with diabetes, while the oldest group comprised patients with hypertension and an implanted stent. Patients with diabetes had the highest glucose and HbA1c concentrations. Patients with hypertension exhibited the highest total cholesterol and LDL-C levels. Triglycerides were highest in the DM+HTN group, whereas HDL-C was lowest in the group of patients with DM and a stent, although this was not statistically significant. The same group had the highest NLR index, while the RPR index was highest in patients with HTN+stent, and the MPR index was highest in the group of patients with DM plus stent. Table 2. Factor analysis in the group of patients with DM and/or various cardiovascular diseases

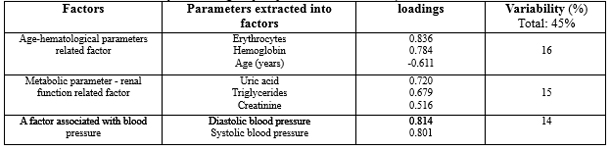

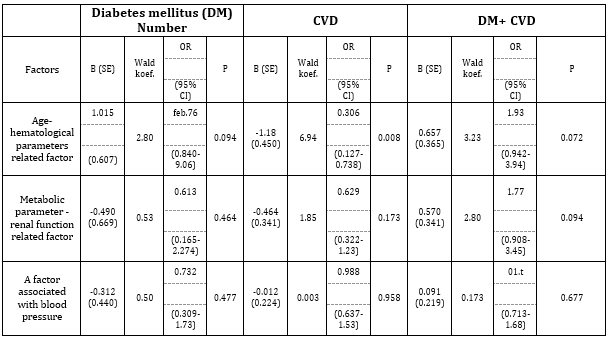

Of all the measured parameters in this study, factor analysis produced three main factors. The first factor, named the “Age-Hematological Parameter Related Factor,” consisted of the number of erythrocytes, hemoglobin concentration, and age (years), and accounted for 16% of the variability. The second factor, the “Metabolic-Renal Function Related Factor,” included uric acid, creatinine, and triglycerides, explaining 15% of the variability. The third factor, the “Blood Pressure Related Factor,” comprised systolic and diastolic blood pressure and accounted for 14% of the variability. The relationship between the factors extracted by factor analysis and the status of metabolic/cardiovascular disease was assessed using logistic regression analysis. Table 3. Logistic regression analysis of the predictors extracted through factor analysis, expressed as factor scores (continuous variables), was performed for DM, CVD, or their combinations.

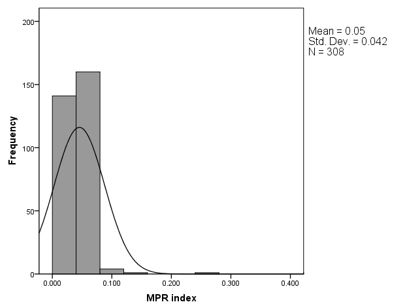

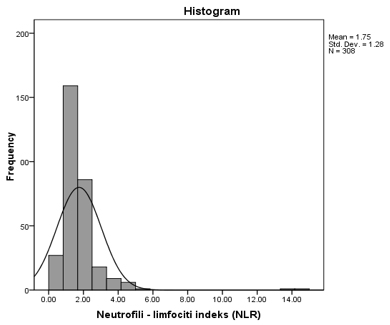

Platelet activation (MPR) and erythrocyte activation (RPR) indices were an important part of this study, aimed at detecting increased blood coagulability in patients using routine parameters obtained from a complete blood count. The distribution of values for these two novel parameters is shown in Figure 1, along with the distribution of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). Figure 1. Distribution of RPR (A), MPR (B), and NLR (C) values in the group of patients with DM and CVD

Table 4. Multiple linear regression analysis of predictors for MPR, RPR, and NLR values

A multiple linear regression analysis was applied to identify

models of significant predictors for the RPR and MPR indices. All

measured parameters and clinical data were included in the analysis,

and the results are presented in Table 4. From the adjusted R² values, it can be concluded that the selected best model of predictors for MPR explains approximately 16.5% of the variability of this parameter, while the RPR parameter variability is explained by the best model at about 14.5%. The NLR value was determined by a model including only one parameter, hemoglobin (adjusted R² = 0.055), indicating that this model explains 5.5% of the variation in NLR. DISCUSSION The results of this study show significant differences in parameters such as BMI, glucose, HbA1c, blood pressure, and lipids among different groups of patients. These differences highlight the need for an individualized approach in the assessment and management of patients with cardiovascular diseases. The observed variations emphasize the importance of regular monitoring of these key parameters to timely identify patients at increased risk of complications. A total of 311 participants were included in the study, with more than half (59.6%) being female. The average age of participants was 58 years. The sample was retrospectively selected through an analysis of patients’ electronic health records who met specific criteria, with a consecutive sampling method. In the prospective part of the study, clinical and laboratory parameters were monitored during each patient visit. Analysis of clinical and laboratory parameters in patients with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases revealed key biomarkers that provide valuable information about the patients’ condition. BMI, glucose, HbA1c, total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides are essential for understanding the pathophysiology and risk associated with different health conditions. BMI is a reliable indicator of body mass relative to height and is often associated with the risk of developing cardiovascular and metabolic disorders [16]. Blood glucose levels and HbA1c are key indicators for diabetes management, reflecting glycemic control and variability, while total cholesterol and its fractions, such as LDL-C and HDL-C, assess the patient’s lipid status [23]. The study by Artha et al. also examined the relationship between lipid profiles, lipid ratios, and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. It showed that higher levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein, triglycerides, and lipid ratios correlate with poorer glycemic control, as indicated by higher HbA1c levels [23]. In contrast, the study by Kidwai et al. observed that high-density lipoprotein levels were lower in patients with poor glycemic control [24]. Accordingly, the LDL-C/HDL-C ratio has been identified as a

significant risk factor for poor glycemic control, with a high ratio

increasing the risk 38-fold. However, it is important to note that

while this ratio is useful in theoretical assessment, in practice,

the prognostic value of lipoproteins (Lp(a)), apolipoprotein A (apo

A), apolipoprotein B (apo B), and the presence of small dense LDL

particles may play a more significant role in risk assessment and

cardiovascular disease management. These findings suggest that lipid

profiles and ratios can serve as predictive markers for glycemic

control, helping to manage cardiovascular risk in patients with

diabetes. Additionally, regular monitoring of lipid levels alongside

glycemic control is emphasized as crucial for reducing

diabetes-related cardiovascular complications.. The study by Britton et al. investigated the correlation between hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), and the risk of developing hypertension (HTA). The aim was to determine whether there is a prospective association between baseline HbA1c values and the incidence of HTA over time, considering the role of body weight. This study is particularly important, as elevated HbA1c may indicate poor blood sugar control, a risk factor for developing hypertension, while BMI is a well-known indicator of body mass that can also influence cardiovascular health. The authors’ conclusions are consistent with the findings of our study [26]. Britton’s study emphasizes the importance of BMI, glucose levels, and HbA1c as key indicators of metabolic health. Elevated BMI may indicate overweight or obesity, factors that can increase hypertension risk due to added strain on the heart and blood vessels. High HbA1c levels suggest chronic hyperglycemia, which can lead to vascular damage and inflammatory processes, further increasing cardiovascular risk. These findings are supported by other published studies [27,28], reinforcing our hypothesis regarding the link between these variables and hypertension risk. Our findings align with previous research showing that elevated HbA1c and BMI are associated with higher hypertension risk. For example, some studies indicate that even mildly elevated HbA1c levels may be indicative of increased HTA risk, while other evidence suggests that interventions aimed at reducing BMI can lower hypertension incidence in patients with metabolic syndrome. These results suggest that weight management and glycemic control may be key elements in preventing hypertension, which is consistent with our study’s findings. Furthermore, an Israeli study from 2021 [29] provides additional evidence that elevated HbA1c and BMI levels significantly contribute to the development of hypertension. These results underscore the need for regular monitoring of metabolic factors such as HbA1c and BMI, especially in patients at increased cardiovascular risk. Taken together, it is clear that HbA1c and BMI are key health indicators that can significantly influence hypertension risk. The results of that study also showed that HbA1c variability is

an independent risk factor for diabetes-related complications.

Approximately 22% of participants had high HbA1c variability, which

was associated with a BMI of 30 or higher. This suggests that

patients with higher BMI often have less stable blood sugar levels,

increasing the risk of complications such as cardiovascular disease

and neuropathy. Additionally, patients with high HbA1c variability

had more frequent visits to diabetes clinics, indicating a more

complex disease profile requiring intensive monitoring and

treatment. These patients often used insulin and ACE inhibitors, and

their age as well as the presence of ischemic heart disease were

also significant factors. The association between high HbA1c

variability, younger age, and high BMI suggests that risk factors

for complications often occur together, creating a more complex

pattern of diabetes management. Indices such as MPR, RPR, and NLR have proven useful in assessing procoagulant activity and inflammatory status, providing important insights into patients’ health. These parameters can serve as early indicators of increased risk in patients with complex comorbidities, enabling timely intervention and tailored therapeutic strategies. MPR, the monocyte-to-platelet ratio, can indicate changes in the immune and coagulation systems. RPR, the reticulocyte-to-platelet ratio, helps assess the regenerative capacity of the bone marrow and coagulation activity. NLR, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, is a simple yet effective marker of inflammation and stress. By using these indices, clinicians can better understand and manage patient risks, potentially improving treatment outcomes and adjusting therapeutic plans according to individual patient needs. Our study results highlight that MPR values were highest in patients with diabetes (DM) and an implanted stent. This index may be particularly useful in assessing thrombotic risk, as it indicates platelet activation, which is often associated with increased blood coagulability. In our research, the presence of a stent and factors such as atrial fibrillation (AF) and other arrhythmias were identified as significant predictors of MPR values, suggesting a higher predisposition to thrombotic events in these patients. Furthermore, RPR values were highest in patients with hypertension (HTA) and an implanted stent. This index may reflect changes in the hematopoietic system and can be useful in evaluating coagulation status. Our study indicated that the presence of a stent, BMI, and creatinine levels significantly influenced RPR values, which is important for identifying patients potentially at increased risk of coagulation-related complications. Although less dominant in our model, NLR was recognized as a significant marker of inflammation. Our findings emphasize that NLR can serve as a useful tool for the early identification of patients at higher risk of complications, allowing clinicians to adjust therapeutic strategies and improve outcomes. When analyzed alongside other clinical and laboratory parameters, NLR contributes to more precise monitoring and management of patients with complex comorbidities. The literature also underscores the importance of other inflammatory markers, such as hsCRP (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein), commonly used to assess inflammatory status and cardiovascular risk. Elevated hsCRP levels have been associated with increased complication risk in patients with chronic conditions, including diabetes and hypertension [37,38]. Compared to NLR, hsCRP offers the advantage of high sensitivity for detecting low-grade inflammation. While NLR provides insight into the balance between neutrophils and lymphocytes, reflecting general immune status, hsCRP directly measures inflammation levels in the body. The complementary nature of NLR and hsCRP enhances understanding of inflammatory processes in patients with complex comorbidities. Studies investigating inflammatory markers, including NLR and hsCRP, have shown that these indices can serve as early indicators of increased risk in such patients [38]. Considering their complementary roles, clinicians may consider using both markers in routine risk assessment, enabling timely intervention and optimized therapeutic approaches. For example, Thurston et al. found that higher NLR values often reflect an increased inflammatory response, which is associated with cardiovascular risks [30]. This study, like ours, suggests that these markers can serve as early risk indicators in patients with complex comorbidities, providing important information on health status and potential cardiovascular complications. Additionally, Li et al., in a study published in early November 2024, highlighted the exceptional value of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in assessing cardiovascular risk [31]. Analyzing data from 2,239 participants with cardiovascular disease (CVD), they found that higher NLR values correlated with increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1999 and 2018, the study demonstrated that higher NLR independently predicted increased mortality risk, even after adjusting for demographic and clinical factors. Each one-unit increase in NLR was associated with a 15% higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 1.15; 95% CI: 1.11–1.19) and a 14% higher risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.08–1.20) in a model including all relevant variables. Restricted cubic spline analysis indicated a nonlinear relationship between NLR and all-cause mortality (p<0.05 for nonlinearity), suggesting that increasing NLR may have a more complex relationship with mortality risk, particularly at higher levels. These findings support our conclusion that NLR, like other inflammatory indices such as MPR and RPR, can be effective indicators for risk stratification and prognosis assessment in patients with CVD. The study emphasizes NLR’s potential as a cost-effective clinical marker. Factor analysis identified the “age-hematologic factor” and “metabolic-renal factor” as significant variables related to risk. These factors consolidate variability among clinical and biochemical parameters, providing deeper insight into the complex interactions contributing to cardiovascular risk. Notably, the blood pressure-related factor showed a significant contribution to overall risk assessment, underscoring the need for its management in clinical practice. Our study identified the “age-hematologic factor,” which includes red blood cell count, hemoglobin concentration, and age. This factor accounted for 16% of variability and demonstrates how age and hematologic characteristics may be associated with increased cardiovascular risk. The association of age with hematologic parameters, such as anemia, is often correlated with higher CVD risk, making our analysis relevant for assessing overall patient health. A relevant study addressing age and hematologic factors in the context of cardiovascular risk is by Truslowa et al. Like our research, it investigated the use of hematologic markers from complete blood counts in developing predictive models for cardiovascular events [32]. That study used Cox proportional hazards models to predict outcomes such as myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, heart failure hospitalization, revascularization, and all-cause mortality. While the modeling methodology differs from ours, the results showed that models including hematologic indices provide better predictions than models using only demographic data and diagnostic codes. Specifically, models performed best in predicting heart failure and all-cause mortality, with concordance indices ranging from 0.60 to 0.80. Consequently, Truslowa et al. highlight the potential of using hematologic markers, such as red blood cell count and hemoglobin concentration, in assessing cardiovascular risk, supporting our observations regarding the “age-hematologic factor.”. The blood pressure factor consists of systolic and diastolic blood pressure and accounts for 14% of variability. Our study highlights the importance of this factor in overall risk assessment. Hypertension (HTA) is a well-known risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), and blood pressure control is essential to reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes. These results are consistent with previously published studies examining the correlation between HTA and CVD [28,33]. The discussion of this factor emphasizes its practical application in clinical settings, where monitoring and managing blood pressure is crucial for preventing cardiovascular events. Limitations of this study include its retrospective design and a sample restricted to a single healthcare institution. Future research could include longitudinal studies to track long-term outcomes, as well as investigation of additional biomarkers that may improve risk assessment in similar patient populations. CONCLUSION The results of this study indicate that inflammatory-hemostatic indices, such as MPR and RPR, together with clinical factors, serve as useful tools for risk assessment in patients with cardiovascular diseases. The highest MPR values were observed in patients with diabetes and an implanted stent, while the highest RPR values were found in patients with hypertension and a stent, suggesting a pronounced inflammatory and procoagulant status in these subgroups. Factor analysis further confirmed the significance of the age-hematological cluster as the sole independent predictor of the presence of cardiovascular disease. These findings underscore the importance of integrating simple, routinely available hematological markers with clinical data to enable early identification of high-risk patients. Incorporating these parameters into daily clinical practice may enhance diagnostics, allow for personalized therapy, and contribute to more effective primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. LITERATURE:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [

Contents

] [ INDEX ]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||