| |

|

|

INTRODUCTION The most common conditions that lead to acute

pain in gynecological practice include ectopic pregnancies, pelvic

inflammatory disease, ruptured ovarian cysts, ovarian torsion,

torsion and degeneration of uterine leiomyomas, and spontaneous

miscarriages. The largest number of ovarian torsions is seen in the

reproductive period, around 71% [2], but it also occurs in fetuses

and neonates, premenarchal girls, pregnant women, and postmenopausal

women. Although the true incidence of torsion is still unknown, data

show that torsion accounts for 2.7% of surgical interventions,

making it the fifth most common condition requiring emergency

surgery [2]. Another study found that 15% of surgically treated

adnexal masses are in torsion [3]. Timely diagnosis is important

both for preserving ovarian function and for preventing subsequent

comorbidities.

PATHOGENESIS AND RISK FACTORS

To understand how torsion occurs, we must first understand the

anatomy of the supporting structures of the uterus and ovaries. The

ovary is a paired intraperitoneal organ with two primary functions:

the production of sex hormones, and the development and release of

the oocyte during ovulation, as well as the formation of the corpus

luteum, which provides sufficient hormonal support to early

pregnancy until placental function is established. What is specific

and remarkable about the ovary is that it can increase its volume

several hundred times during a woman’s reproductive period without

pathological clinical manifestations [4].

The ovary is a mobile structure, suspended from the pelvic wall by

the infundibulopelvic ligament (also called the suspensory ligament

of the ovary), through which the ovarian artery passes, and attached

to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament (ligamentum ovarium

proprium), through which the ovarian branch of the uterine artery

passes. In addition to providing support, these ligaments also serve

a nutritive role, as the blood vessels supplying the ovary run

through them, ensuring dual vascularization of the ovary [5].

Torsion occurs as a result of partial or complete rotation of the

adnexal supporting structures, during which the ovary and fallopian

tube rotate around both the infundibulopelvic and utero-ovarian

ligaments, resulting in partial or complete obstruction of ovarian

blood flow [6,7,8]. The thin walls of the veins are more prone to

complete occlusion compared to the muscular walls of arterial

vessels. Continuous arterial inflow without venous outflow leads to

edema with visible ovarian enlargement. Further vascular compression

results in ovarian ischemia, leading to necrosis, local hemorrhage,

and loss of function [9]. Most often, both the ovary and the

fallopian tube undergo torsion simultaneously, although isolated

torsion of the ovary or tube may occur, referred to as partial

torsion. Torsion involving paraovarian or paratubal cysts has also

been described [6]. The right ovary is more frequently affected than

the left, possibly because the right utero-ovarian ligament is

longer, and the presence of the sigmoid colon prevents torsion on

the left side [8,10]. Bilateral asynchronous ovarian torsion is also

possible, though rare [11]. The severity of symptoms and

morphological ovarian changes depends on the type and degree of

vascular occlusion. Based on anatomical features and clinical

findings, we can define risk factors for adnexal torsion. Greater

ovarian mobility is associated with torsion in premenarchal girls,

who have elongated infundibulopelvic ligaments. In this population,

more than half of patients have morphologically normal ovaries.

After this premenarchal period, with puberty, the incidence of

ovarian torsion decreases due to shortening of the infundibulopelvic

ligaments. Risk factors in premenarchal girls may also include the

presence of functional cysts or benign tumors, most commonly

teratomas and cystadenomas [12,13,14].

Ovarian torsion has also been described in the fetal period

(ultrasound may monitor cyst growth and secondary changes such as

hemorrhage, calcifications, or resorption) and in neonates [15].

The highest percentage of ovarian torsions occurs in women of

reproductive age with adnexal changes such as functional ovarian

cysts and benign tumors [8,9,16]. Malignant tumors and endometriotic

cysts are rarely the cause of ovarian torsion. In case series, the

percentage of malignant ovarian tumors associated with torsion is

reported to be below 3%. This is because such lesions cause

peritoneal reactions and adhesions that fix the mass, thereby

limiting its mobility [17]. More than 80% of patients with ovarian

torsion have ovarian masses larger than 5 cm in diameter. The size

of the ovarian mass correlates with the risk of torsion. In a series

of 87 case studies, ovarian masses ranged widely from 3 to 30 cm,

with an average of about 9.5 cm [18]. About 10–22% of ovarian

torsions occur during pregnancy. The incidence is somewhat higher

between the 10th and 17th weeks of gestation in the presence of

ovarian masses larger than 4 cm. Ovulation, the corpus luteum, and

ovulation induction in infertility treatment may cause ovarian

hyperstimulation syndrome, with multiple large cystic ovarian

changes that are prone to torsion. Polycystic ovary syndrome is also

a risk factor [19]. On the other hand, in patients who have

undergone a surgical procedure, the incidence of ovarian torsion is

about 2–15%, typically due to strangulation of the ovarian pedicle

around an existing adhesion. Recurrent torsion has also been

described, and studies show that individuals who have experienced

ovarian torsion once are at increased risk of developing torsion

again—either of the same ovary (“salvage ovary”) or of the

contralateral ovary. [8].

Clinical presentation and clinical findings Ovarian torsion caused

by the presence of an adnexal mass results in a variety of symptoms,

clinical signs, and presentations. The most common symptom is acute,

sharp pain in the lower abdomen or pelvis, accompanied by nausea and

vomiting (70%) in women of reproductive age, in the presence of an

adnexal mass or enlarged ovaries in PCOS or ovarian hyperstimulation,

or in women with a history of prior ovarian torsion [17,18,20]. Some

patients experience only nausea without vomiting. Abdominal pain is

most often intermittent, colicky in nature, with gradual

intensification and relief, although it may also be continuous. The

pain arises secondarily due to occlusion of the vascular pedicle and

is refractory to analgesics. It may radiate to the inguinal region

or flank. Premenarchal patients may report diffuse abdominal pain,

as they often find it difficult to localize the discomfort. In this

group, vomiting is the most common symptom in the absence of adnexal

pathology—this represents a vagal reflex response due to peritoneal

irritation. In neonates, torsion may present with feeding

difficulties, abdominal distension, vomiting, and irritability.

Ovarian torsion without infectious pathology may also be accompanied

by low-grade fever. The low-grade fever is explained by necrotic

changes in the torted ovary and occurs in 2–20% of patients.

Physical examination may reveal low-grade fever, abdominal

tenderness, abdominal pain, and a pelvic adnexal mass. A further

diagnostic challenge is that 30% of patients—especially those in the

premenarchal period—may have neither abdominal pain nor abdominal

tenderness. [17,18,21-24].

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ovarian torsion most often requires a combination

of anamnestic data, clinical examination, and imaging methods. The

first approach to the patient is the physical examination and taking

the medical history. Anamnestic data may indicate a recent diagnosis

of an adnexal mass, recurrent abdominal pain, and low-grade fever.

In children aged 2–14 years, with high sensitivity and positive

predictive value, the Bolli score can be applied. The Bolli score

includes only the patient’s clinical data but not imaging methods

and identifies three useful clinical variables on the basis of which

the ovarian torsion score is established: the age of the child, the

duration of pain, and vomiting. –Number of points – number of years,

minus three points if vomiting is present, plus one point if the

duration of pain is longer than 12 hours. The cut-off value of the

Bolli score in girls is 11.5, a lower score indicating a higher

probability that ovarian torsion is present. [25,26].

LABORATORY TESTING should include hematocrit, leukocyte

count, human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), electrolytes, and

inflammation parameters—C-reactive protein (CRP) [2,22]. Laboratory

analyses may be completely normal, may indicate anemia in the case

of corpus luteum rupture, or leukocytosis and elevated CRP due to

tissue necrosis and consequent inflammation. The level of

interleukin 6 is also elevated and indicates increased oxidative

stress in torsion, but it is also a nonspecific sign of inflammation

and is not routinely performed in our clinical practice [27,28].

Determining tumor markers has not proven to be sufficiently

sensitive or specific, although the elevation of certain tumor

markers may indicate the nature of the torted adnexal mass. The

physical exam is focused on abdominal palpation in order to detect a

tumor mass and assess the presence of peritoneal irritation. Imaging

studies are the most important. Ultrasound is the first-line

diagnostic tool [29,30].

In the pediatric population, transabdominal ultrasound with a full

bladder is the initial imaging method for evaluating torsion. The

sensitivity of transabdominal ultrasound in the pediatric population

is 92–93%, with a specificity of 96–100%. In adult women,

transvaginal ultrasound shows excellent specificity but variable

sensitivity, ranging from 35–85% [31]. What is monitored on

ultrasound is ovarian volume, presence of edema, presence of an

adnexal mass, presence of free fluid, and color Doppler of ovarian

or tumor mass blood vessels. The presence of a difference in ovarian

volume with its displacement is a pathognomonic sign of ovarian

torsion. Another sign is the presence of edema of normal ovarian

tissue. In the literature, it is described as the presence of

peripheral follicles with hyperechogenic halos in the ovary without

cystic changes or tumors — strings of pearls. The presence of

ovarian edema should not be mistaken for the presence of a solid

ovarian tumor.

The torted ovary may be rounder and enlarged compared to the

contralateral one due to swelling of vascular and lymphatic vessels.

There may be normal, reduced, or completely absent blood flow

through the vessels of the torted ovary [31–34]. The whirlpool sign

is a highly sensitive and specific sign for the diagnosis of ovarian

torsion. The whirlpool sign indicates the twisted vascular pedicle,

and Doppler sonography reveals circular blood vessels within the

mass [32]. Finally, a small amount of free fluid may be present in

the pouch of Douglas [31]. The greatest diagnostic challenge is

torsion without twisting of the ipsilateral ovary. It has been shown

that 31% of all torsions are incomplete adnexal torsions. A useful

sign of torsion involving only the tube but not the ovary is the

presence of three or more cysts in one row [35]. The combination of

free fluid in the pelvis, an enlarged ovary, and vascular

abnormalities increases the sensitivity and specificity of

ultrasound findings. CT of the abdomen and pelvis shows high

sensitivity and specificity in the evaluation of suspected torsion

[36] and may show an enlarged ovary, its displacement and pulling of

the uterus to that side, thickening of the cystic mass, ascites,

thickened walls of the tube [36,37]. The definitive diagnosis is

made in the operating room by direct visualization of the specimen.

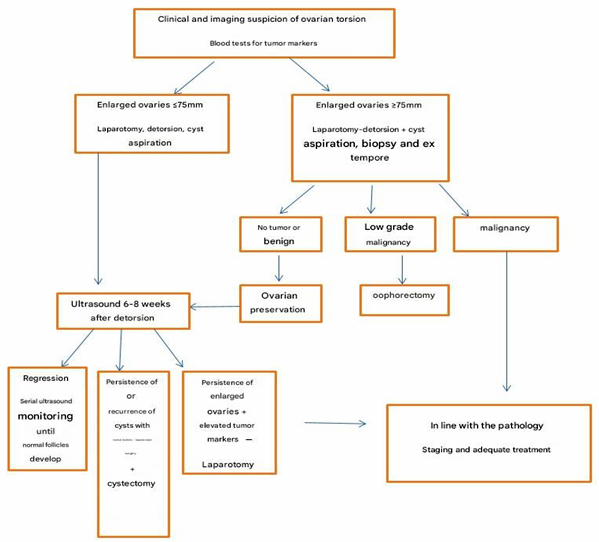

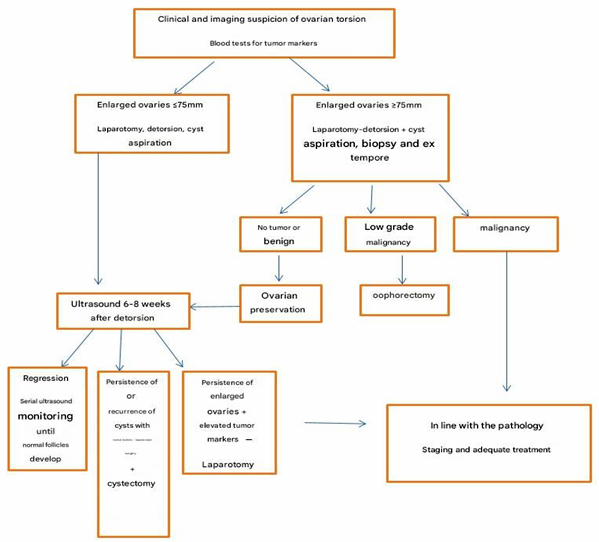

Algorithm 1. Algorithm for management in cases of

clinical and imaging suspicion of ovarian torsion.

Treatment and assessment of ovarian viability

Treatment involves surgical management and at the same time

confirmation of the diagnosis. Early diagnosis and surgical therapy

are necessary in order to protect ovarian and tubal function and to

prevent more serious morbidity. Minimizing the total time during

which the ovary is in ischemia is a key component of therapy, but

the time required for ovarian necrosis to occur is unclear. [37,38].

Picture 1. Surgery of a torted ovarian fibroma

(Dr. Janković, General Hospital Pirot)

As long as the venous and lymphatic vessels are occluded, the

patient may have symptoms for some time before the arterial vessels

become occluded [30,40,41]. In a retrospective study of the

pediatric population, the median time to save the ovary before

detorsion was 10.8 hours. If detorsion is performed within the first

8 hours, the ovary is preserved in 40% of cases, and within the

first 24 hours in 33% [42]. This finding is consistent with data

showing that in women, the percentage of preserved ovaries is 30% if

surgery is performed within the first 24 hours from the onset of

symptoms [43,44]. Different studies show varying times from symptom

onset to detorsion in order to preserve the ovary. Animal studies

have shown that necrosis can occur 36 hours or more after occlusion.

Pediatric and adult populations show good long-term outcomes after

detorsion of either hemorrhagic or ischemic ovaries, with normal

follicle production later in life in 90–94% of cases described

[45,46]. There are two surgical treatment methods — laparoscopy and

laparotomy. Laparoscopy represents a reasonable alternative. The

benefits of laparoscopy include reduced need for analgesics, early

mobilization, cosmetic advantage, and earlier discharge to home

care. An additional advantage is that laparoscopic ovarian

cystectomy is associated with a lower incidence of postoperative

adhesions compared to laparotomy [47]. Laparotomy is recommended

when a malignant process is suspected. What is essential is the

assessment of ovarian viability and preservation of its function.

The only way to assess the viability of the ovary is by gross visual

inspection. Conventionally, a dark and enlarged ovary may be only in

venous or lymphatic congestion and may appear nonviable, but there

is a substantial probability that it is a viable ovary that can

regain function after detorsion [46]. There are other methods to

assess ovarian viability, such as injecting fluorescein and

observing the flow under ultraviolet light [48]. Another method is

ovarian bivalving, i.e., laparoscopically making an incision in the

ovary with an electric hook (L-hook) after detorsion and observing

whether there is blood flow at the cut surface. This also serves a

therapeutic purpose by reducing pressure caused by venous and

lymphatic congestion [49]. There is no precisely determined time for

ovarian necrosis to occur. A definitive sign of ovarian necrosis is

a gelatinous formation that disintegrates upon manipulation. What is

expected from surgical treatment? Ideally, detorsion [50], detorsion

with oophoropexy, ovarian cystectomy (recommended for benign cysts

after detorsion), or salpingo-oophorectomy in cases of suspected

malignancy, necrotic ovaries, and postmenopausal women.

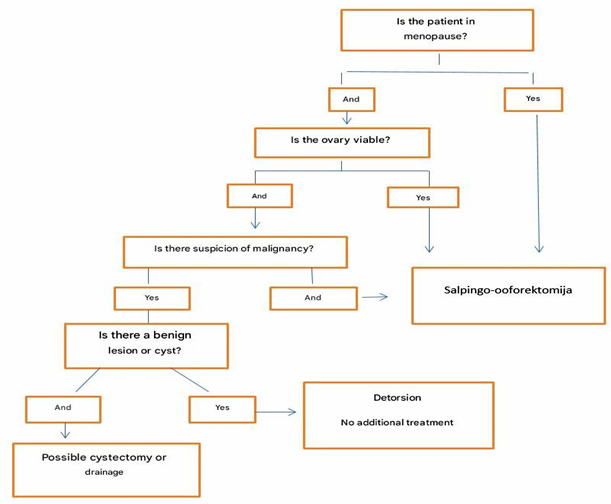

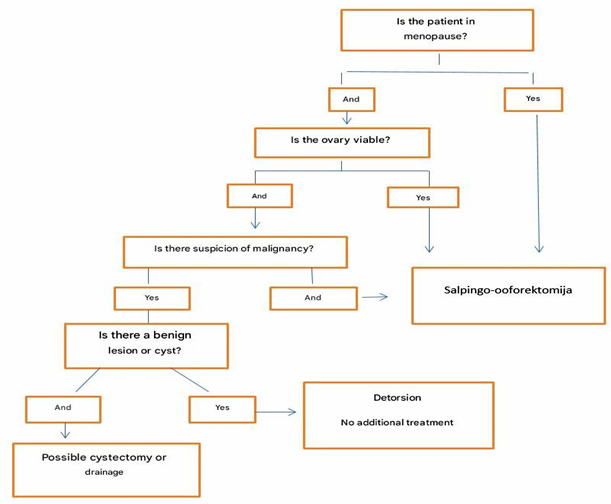

Algorithm 2. Procedure in menopausal women

CONCLUSIONS:

- Ovarian torsion mainly affects women of reproductive age,

but a significant percentage also occurs in the premenarcheal

period, in pregnant women, and in postmenopausal women.

- Ovarian torsion occurs due to complete or partial rotation

of the ovary and fallopian tube, leading to obstruction of

vascular flow.

- Crucial factors for ovarian torsion include the presence of

an ovarian mass in women of reproductive age.

- Almost 90% of women experience abdominal pain that begins

suddenly, is sharp, and intermittent in nature.

- Up to 70% experience nausea and vomiting.

- Nearly one-third of patients with torsion have no abdominal

or pelvic pain on examination.

- Although ultrasound is used as the primary diagnostic

modality in the evaluation of ovarian torsion with high

specificity, a normal ultrasound finding cannot effectively rule

out the diagnosis.

- CT of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast can be helpful

in diagnosis.

- In the evaluation, findings for reduced or absent ovarian

enlargement, peripheral displacement of follicles, enlarged

ovaries with follicular stroma, and thickened fallopian tube are

considered significant

REFERENCE:

- Franco PN, García-Baizán A, Aymerich M, Maino C,

Frade-Santos S, et al. Gynaecological Causes of Acute Pelvic

Pain: Common and Not-So-Common Imaging Findings. Life

(Basel).2025;13(10):2025.

- Hibbard LT.Adnexal torsion. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1985;152:456-61.

- Bouguizane S, Bibi H, Farhart Y, et al. Adnexal torsion: a

report of 135 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod.

2003;32(6):535–40.

- Gibson E, Mahdy H. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Ovary.

StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island 2019.

- Ying J, Feng J, Hu J, Wang S, Han P, Huang Y, et al. Can

ovaries be preserved after an ovarian arteriovenous

disconnection? One case report and a review of surgical

treatment using Da Vinci robots for aggressive ovarian

fibromatosis. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12(1):52.

- Huang C, Hong MK, Ding DC. A review of ovary torsion. Tzu

Chi Med J. 2017;29(3):143-7.

- Sanfilippo JS, Rock JA. Surgery for benign disease of the

ovary. In: TeLinde's Operative Gynecology, 11th ed., Jones HW,

Rock JA (Eds), Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

- Beaunoyer M, Chapdelaine J, Bouchard S, Ouimet A.

Asynchronous bilateral ovarian torsion. J Pediatr Surg 2004;

39:746-9.

- Takeda A, Hayashi S, Teranishi Y, et al. Chronic adnexal

torsion: An under-recognized disease entity. Eur J Obstet

Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017; 210:45.

- Huchon C, Fauconnier A. Adnexal torsion: a literature

review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010; 150:8-12.

- Raicevic M, Saxena AK. Asynchronus bilateral ovarian

torsions in girls-systematic review. World J Pediatr 2017;

13:416-20.

- Oltmann SC, Fischer A, Barber R, et al. Cannot exclude

torsion – a 15-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1212–6.

- Smorgick N, Melcer Y, Sarig-Meth T, et al. High risk of

recurrent torsion in premenarchal girls with torsion of the

normal adnexa. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:1561–5.

- Breech LL, Hillard PJ. Adnexal torsion in pediatric and

adolescent girls. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:483–9.

- Heling KS, Chaoui R, Kirchmair F, et al. Fetal ovarian

cysts: prenatal diagnosis, management and postnatal outcome.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002; 20:47-50.

- Ssi-Yan-Kai G, Rivain AL, Trichot C, et al. What every

radiologist should know about adnexal torsion. Emerg Radiol.

2018;25(1):51–9.

- Tsafrir Z, Hasson J, Levin I, et al. Adnexal torsion:

cystectomy and ovarian fixation are equally important in

preventing recurrence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012;

162:203-5.

- Houry D, Abbott JT. Ovarian torsion: a fifteen-year review.

Ann Emerg Med 2001; 38:156-9.

- White M, Stella J. Ovarian torsion: 10-year perspective.

Emerg Med Australas 2005;17:231-7.

- Sasso RA. Intermittent partial adnexal torsion after

electrosurgical tubal ligation. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc

1996; 3:427-30.

- Huchon C, Fauconnier A. Adnexal torsion: a literature

review. Eur J Obstet GynecolReprod Biol. 2010;150(1):8–12.

- White M, Stella J. Ovarian torsion: 10-year perspective.

Emerg Med Australas. 2005;17(3):231–7.

- Sasaki KJ, Miller CE. Adnexal torsion: review of the

literature. J Minim InvasiveGynecol. 2014;21(2):196–202.

- Gasser CRB, Gehri M, Joseph JM, Pauchard JY. Is it ovarian

torsion? A systematic lit-erature review and evaluation of

prediction signs. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32(4):256–61.

- P. Bolli, S. Schadelin, S. Holland-Cunz, P.

Zimmermann.Ovarian torsion in children:development of a

predictive score. Medicine 2017;96(43) :e8299.

- M. B. Pepys, G. M. Hirschfield. C-reactive protein: a

critical update. J ClinInvest 2003;111(12):1805-12.

- Cohen SB, Wattiez A, Stockheim D, et al. The accuracy of

serum interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor as markers for

ovarian torsion. Hum Reprod 2001; 16:2195-7.

- Daponte A, Pournaras S, Hadjichristodoulou C, et al. Novel

serum inflammatory markers in patients with adnexal mass who had

surgery for ovarian torsion. Fertil Steril 2006; 85:1469-72.

- Taufiq DM, Bharwani NM, Sudderuddin SA, Rockall AG, Stewart

VR. Adnexal torsion: review of radiologic appearances.

Radiographics. 2021;41(2): 609–24.

- Robertson JJ, Long B, Koyfman A. Myths in the evaluation and

Management of Ovarian Torsion. J Emerg Med. 2017;52(4):449–56.

- Bridwell RE, Koyfman A, Long B. High risk and low prevalence

diseases: Ovarian torsion. Am J Emerg Med. 2022 ;56:145-150.

- Moro F, Bolomini G, Sibal M, et al. Imaging in gynecological

disease (20): clinical and ultrasound characteristics of adnexal

torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2020; 56:934-43.

- Adnexal Torsion in Adolescents: ACOG Committee Opinion No,

783. Obstet Gynecol 2019; 134:e56. Reaffirmed 2021.

- Janković N, Janković M, Ristić Petrović A, Dimitrijević S. A

rare disease which lead to avoidable ovary loss. Ovarian

torsion-Case reports. Med. Pregl. 2025.(in press)

- Pignataro JN, Schindler L. Isolated Fallopian Tube Torsion:

Diagnosis and Management of a Gynecologic Emergency. Cureus.

2023;15(9):e46260.

- Dhanda S, Quek ST, Ting MY, et al. CT features in surgically

proven cases of ovarian torsion—a pictorial review. Br J Radiol.

2017; 90(1078):20170052

- Schlaff W, Lund K, McAleese K, Hurst B. Diagnosing ovarian

torsion with computed tomography. A case report. J Reprod Med.

1998;43(9):827–30.

- Spinelli C, Piscioneri J, Strambi S. Adnexal torsion in

adolescents: update and review of the literature. Curr Opin

Obstet Gynecol. 2015;27(5):320–5.

- Dasgupta R, Renaud E, Goldin AB, et al. Ovarian torsion in

pediatric and adolescent patients: A systematic review. J

Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(7):1387–91.

- Cass DL. Ovarian torsion. Semin Pediatr Surg.

2005;14(2):86–92.

- Cicchiello LA, Hamper UM, Scoutt LM. Ultrasound evaluation

of gynecologic causes of pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin North

Am. 2011;38(1):85–114.

- Anders JF, Powell EC. Urgency of evaluation and outcome of

acute ovarian torsion in pediatric patients. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med. 2005;159(6):532–5.

- Shalev J, Goldenberg M, Oelsner G, et al. Treatment of

twisted ischemic adnexa by simple detorsion. N Engl J Med.

1989;321(8):546.

- Oelsner G, Bider D, Goldenberg M, Admon D, Mashiach S.

Long-term follow-up of the twisted ischemic adnexa managed by

detorsion. Fertil Steril. 1993;60(6): 976–9.

- Cohen SB, Oelsner G, Seidman DS, Admon D, Mashiach S,

Goldenberg M. Laparoscopic detorsion allows sparing of the

twisted ischemic adnexa. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc.

1999;6(2):139–43.

- Pansky M, Abargil A, Dreazen E, Golan A, Bukovsky I, Herman

A. Conservative management of adnexal torsion in premenarchal

girls. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(1):121–4

- Lundorff P, Hahlin M, Kallfelt B, Thorburn J, Lindblom

B.Adhesionformation after laparoscopy surgery in tubal

pregnancy: a randomizedtrial versus laparotomy. Fertil Steril.

1991;55 (5):911-5.

- McHutchinson LL, Koonings PP, Ballard CA, d'Ablaing G 3rd.

Preservation of ovarian tissue in adnexal torsion with

fluorescein. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993; 168:1386-8.

- Styer AK, Laufer MR. Ovarian bivalving after detorsion.

Fertil Steril 2002; 77:1053-5.

- Wang JH, Wu DH, Jin H, Wu YZ. Predominant etiology of

adnexal torsion and ovarian outcome after detorsion in

premenarchal girls. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2010; 20:298-301.

|

|

|

|