|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [

Contents

] [ INDEX ]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

History of medicine TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH PERIODONTITIS (PERIODONTAL DISEASE) THROUGH HISTORY Miloš Silevski (1), Dragana Daković (2) (1) DENTAL OFFICE “DR VUCA”, BELGRADE, SERBIA; (2) MILITARY MEDICAL ACADEMY, CLINIC FOR DENTISTRY, BELGRADE, SERBIA |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Download in pdf format | Summary: Preserved

biological remains of teeth and jaws from prehistoric times, showing

signs of periodontal tissue diseases, indicate that these diseases

are as old as humanity itself. There are numerous evidence of human

interest in oral healthand it dates back centuries ago. The oldest

civilizations and their understanding of dental pain and therapeutic

procedures form the foundation of the science we learn and know

today. Starting from ancient Greece, Rome, and the Renaissance,

where the brightest minds tackled human issues, earning the

gratitude of generations that followed, to modern times where

maintaining oral health is considered one of the vital components of

a healthy human organism. This medical article aims to examine the

development of periodontology as a branch of dentistry, compare the

therapies and perceptions of those who studied it, and attempt to

summarize the achievements of dental science as we know it today. Keywords: History of periodontitis treatment, periodontal tissue, gingiva, the periodontal ligament, tooth cement, alveolar bone, alveolus |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

INTRODUCTION The, periodontal tissue (supporting structure

of the tooth) consists of the gingiva, alveolar bone, the

periodontal ligament, and root cementum. These tissues, despite

their histological differences, have a common function: to firmly

hold the connection of the tooth within the alveolar bone. Today,

material, written and biological remainsfrom earlier periods are

available, allowing us to create a clearer imageof how the science

evolved regarding the treatment of periodontal diseases, from

ancient times to the present.

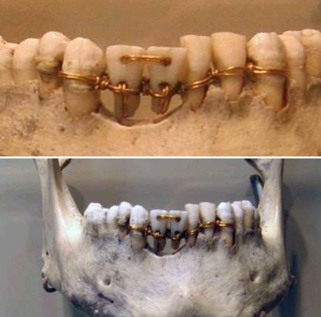

Figure 1. Golden wire ligature used as a

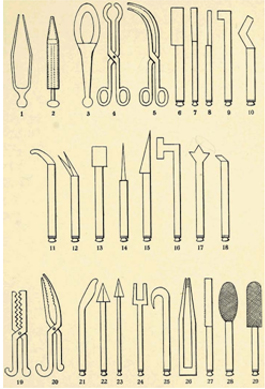

therapeutic procedure in the treatment of tooth loosening The most prominent figure in medicine in ancient Greece (750–320 BC) was Hippocrates (460–370 BC). He is still considered as the father of medicine, and his oath is taken in many countries after completing studies in medicine and relatedmedical fields. His contribution to modern medicine iswell known. Among other things, he recognized the importance of clinical observation and patient evaluation. He spoke aboutthe role of nature in the healing process and opposed therapeutic methods that could harm the patient. Hippocrates introduced the concept of disease prevention through a healthy diet and healthy environment. He described jaw dislocations and fractures as well as ulcers occurring in the mouth due to systemic diseases. One of the topics he dealt withwas the etiology of periodontal diseases, along with an explanation of tooth eruption. He attributed gum inflammation to the accumulation of hard deposits on teeth (i.e. tartar) and spleen diseases. In one patient with a spleen disease, he noted a swollen abdomen, acute pain and gums that separated from the teeth with an unpleasantsmell [18]. In addition to Hippocrates, Aristotle (384–322 BC) was a leading scientist, teacher and philosopher in ancient Greece. He researched the etiology and observed symptoms of oral diseases. Aristotle wrote about periodontal diseases and tooth decay, described the morphology of teeth and considered the importance of occlusion. He studied the harmful effects of sugar and sticky foods on teeth and periodontal tissues. As an example, he examined the impact of figs on periodontal health, pointing out their sweetness and sticky texture as causes of cavities and gum inflammation. Aristotle believed that deposits remained in periodontal tissues and between teeth, in areas where their removal was difficult [4]. In ancient Rome, physicians primarily focused on preventing periodontal diseases. During this period (10 BC–25 AD), oral hygiene was considered an important factor in public health. Many preserved documents mention the use of toothbrushes and their significance [11]. The first prominent physician was Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 BC–10 AD). In his books, which contained all existing knowledge of medicine at that time, he described various treatments for periodontal diseases alongside the significance of prevention and oral hygiene. In one of his works, he wrote that bleeding gums should be treated with apple juice and vinegar. He also described using cauterization to remove enlarged gums and advised applying honey and red wine to the area after the procedure [5]. The Islamic Golden Age, spanning from the 8th to 13th centuries AD, marked significant cultural, scientific, and technological advancements in the Islamic world. Among the notable figures of this era was Abulcasis, the most renowned physician of the western Caliphate. He described hemophilia, surgical removal of metastasized tumors and the use of cauterization to stop bleeding from damaged blood vessels. Abulcasisrealized that deposits and tartar on teeth were etiological factors in the development of periodontal diseases. He understood the importance of removing deposits from both the teeth and spaces beneath the gums, leading him to design and create a series of instruments for effectively removing these deposits. These instruments were the forerunners of modern dental scalers and curettes [15]. (Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Sketches of periodontal instruments

designed by Abulcasis The Renaissance brought new momentum to art, culture, medicine and dentistry. Books and writings emerged, describing human anatomy more thoroughly than before, thanks to advancements in dissection methods [6]. The invention of the printing press enabled the production of books in greater numbers and the translation of medical texts contributed to the spreadingof medical knowledge. The pursuit of science and research became more accessible and many took advantage of this opportunity.The first printed book in the field of dentistry was published in 1530 under the title "Little Medicinal Book for All Kinds of Diseases and Infirmities of the Teeth" by ArtzneyBuchlein. It included descriptions of previously known information, therapeutic methods and the experiences of physicians from ancient Greece and Rome, as well as observations and knowledge from Arab physicians during the Islamic Golden Age. Several chapters of this book discussed diseases of the gingiva andperiodontal tissue [7]. Bartolomeo Eustachio (1500–1574), an Italian scientist, made significant contributions to medical science, particularly in human anatomy. Alongside detailed descriptions of tooth structure and pulp, he described oral diseases and offered treatment methods. His approach to treating periodontitis and periodontal disease was considered modern for that era. He advised the removal of dental tartar and excision of pathologically altered tissue [9]. Surgical procedures on oral tissues were the subject of his further research.AmbroiseParé (1510–1590) was the first to describe oral surgical and other procedures, earning recognition as the greatest surgeon of the Renaissance. He refined numerous surgical instruments for oral procedures and understood the importance of tartar in the etiology of gingival and periodontal diseases, emphasizing the necessity of its removal [8]. In the 18th century, two names stand out as particularly significant for the further development of periodontology: Pierre Fauchard and John Hunter. Fauchard, a French navy warsurgeon, was particularly interested in oral diseases affecting sailors aboard ships. The condition that caused the most trouble among sailors was scurvy. His skills became widely known and he soon gained fame. He successfully was treatingdental cavities, tartar issues and the removal of benign tumors in the oral cavity. Fauchardis notable for performing the first gingivectomyprocedure in 1742, a method for removing excess gingival tissue. In his books, he detailed the anatomy of the gingiva, changes in its structure and morphology, and epulides [15]. John Hunter, a British physician and scientist, whoanalyzed in detail and studied human anatomy. During his lifetime, he collected over 13,000 anatomical specimens, which he studied and described in his publications. His manuscripts on head anatomy were supplemented with illustrations of jaw and facial bones, as well as primary and permanent teeth. Hunter also described the morphology of teeth with root canals and pulp tissue (Figure 3). As a surgeon, he believed that all diseases and changes in the bony and soft tissues of the oral cavity should be treated by surgeons. He tracked the progression of dental cavities, describing “white spot fields” on teeth that later advanced to brown areas representing decayed tooth tissue. Hunter also described "pockets" in the bone and their destructive effects, leading to tooth loosening [10].

Figure 3. The book by John Hunter from the year

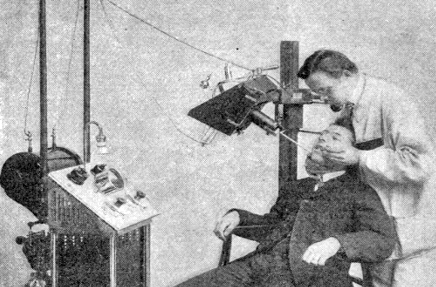

1771 The 19th century was a period of great medical discoveries and advancements. Research in pathology and microbiology, the discovery of anesthesia and X-rays revolutionized diagnostic concepts and improved the treatment of oral diseases. Germany and America took leading roles in clinical therapeutic procedures and research. John Riggs (1811–1855) was a prominent physician who focused on periodontal diseases and their treatment. His interest in gingiva and its diseases began early in his clinical career. Due to his success in diagnosis and treatment, as well as his decision to dedicate his clinical and scientific work entirelyto periodontal tissue diseases, Riggs is considered the first periodontistin history. His importance in understanding and treating periodontal diseases is highlighted by the fact that the disease now recognized as periodontitis was once called "Riggs' disease." [11]. Riggs opposed gingival surgical resection, a procedure widely used at the timeand insisted on removing pathological tissuein the subgingivalregion. He emphasized the importance of prevention and oral hygiene, particularly tooth brushing. Leonard Koecker (1785–1850), a dentist and researcher, also played a significant role in the development of periodontology in the 19th century. His observations and innovative ideas reshaped the understanding of periodontal diseases. By examining and following patients, he noticed that periodontal diseases begin with gingival inflammation, which he described as "slowly progressing." He identified hard deposits on teeth as a critical etiological factor in disease onset and emphasized the necessity of regular tooth brushing after meals. Koeckeralso addressed the concept of "focal infection," suggesting that teeth with poor prognosis and retaineddental roots should be extracted to prevent diseases in distant organs [21]. The 20th century saw continuous development in science and technology, partly influenced by the wars of this era. The pursuit of power and overcoming adversaries required the involvement of the brightest minds across all fields. The discovery of antibiotics led to successful treatments for numerous infectious diseases. The use of X-rays and magnetic resonance improved diagnostic accuracy and opened doors to innovative therapeutic procedures, such as organ transplants. Dentistry followed medical advancements, integrating technological and scientific achievements. Following military medicine, dentistry adopted X-rays as a diagnostic tool [12] (Figure 4). Machine-powered dental instruments began replacing manual ones, and dental chairs with reflectors were designed. Local anesthesia started being used during interventions. The discovery of fluoride's preventive role in cavity formation improved oral health and prevented dental and periodontal diseases. New periodontal instruments were created to aid in diagnosing and treating periodontal diseases. The first periodontal probe, then called a "periodontometer", was designed, allowing better diagnosis of periodontal pockets and measurement of their depth. Measurements recorded during follow-ups enabled dentists to monitor treatment outcomes [13]. Both causal, non-surgical therapy and surgical procedures of the periodontal tissueunderwent itsrenaissance. Robert Newman and Leonard Widmanwere pivotal figures in the development of periodontal surgery during this period. Widman's flap procedure from 1918 marked a breakthrough in periodontal surgical advancements. This innovative method featured a trapezoidal flap shape with two vertical relaxation incisions, providing greater mobility and better access to pathological tissue [19]. A decade later, in 1931, Kirkland introduced a new approach called "subgingival open-field curettage." This procedure aimed to preserve healthy periodontal tissue and suppressinflammation, by removinginflamed and pathologically altered tissue [20]. Post-World War II, a new generation of scientists and clinicians took over the role from their predecessors. A world recovering from significant losses began focusing on innovative solutions and rebuilding society. Caring for people's needs became a societal norm. In the U.S., oral health improved continuously thanks to preventive measures introduced. Surgical procedures for the periodontal tissuebecame increasingly widespread, with investments made in new materials and instruments. A notable development in treating periodontal diseases was the local use of penicillin. Administered in lozenge form, its slow breakdown ensured prolonged concentration in the oral cavity. Indications included acute ulcerative gingivostomatitisand acute streptococcal tonsillitis. Penicillin was also used preventively before certain oral surgical interventions and in patients with systemic diseases. Later, penicillin became the drug of choice for intramuscular administration in patients with acute and necrotizing gingival changes [14].

Figure 4. The first commercial dental X-ray

machine (1905) This period also marks the birth of a new dental discipline –

implantology. The idea of replacing an extracted tooth with another

tooth or material dates back to the earliest human civilizations

(Figure 5). However, it was not until the 20th century that

implantologybegan to develop as a science. A major breakthrough in

implantologytherapy was the discovery by Swedish orthopedic surgeon

Brånemark. During one surgical procedure, he used biocompatible

titanium intraosseousimplants and later described the term "osseointegration,"

which became the foundation of modern implantology [22].

Figure 5. Mandible from the Mayan period , with

three implanted pieces of shell in a toothless space CONCLUSION Modern periodontology has little in common with the treatment methods practiced in past centuries. One of the few similarities is that periodontal diseases continue to be a challenge for humanity. Bleeding gums, pain, and tooth loosening are just some of the symptoms that drove earlier civilizations to search for solutions to this problem. For this reason, historical data is of great importance in understanding the development of periodontology. Today, periodontology has advanced significantly and encompasses a wide range of areas, starting from diagnosis and non-surgical therapy to occlusaltherapy, resectiveprocedures and the regeneration of hard and soft tissues of the tooth-supporting structures. LITERATURE:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [

Contents

] [ INDEX ]

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||