| |

|

|

Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Diseases

Cardiovascular diseases present the number one cause of death

worldwide. WHO estimates that 17.3 million people die from CVDs and

predicted mortality rate by 2030 is more than 23 million people. It

is estimated that 30% of all deaths are due to CVDs. Despite the

trend of lower mortality rate due to CVDs last years, they are still

the main cause of mortality. Burden of CVDs is even more pronounced

in low- and middle-income countries, which account for 80% of all

CVD caused deaths world-wide [1].

Every other person in Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia die from CVDs;

countries are in the group of countries having high risk of CVD

mortality [2, 3, 5]. In Croatia, 48.7% of deaths were due to CVDs in

2011 [2], in Montenegro 56.8% of deaths were due to CVDs in 2006

[3], while in the Republic of Serbia 56.0% of deaths were due to

CVDs in 2007 [4].

National health survey conducted in Mon-tenegro in 2008 showed that

42.8% of adults were diagnosed with chronic disease and the leading

diagnoses were the following: hypertension, hyperlipidemias, and

chronic heart disease [3]. Data from Serbian 2006 study titled

„Health of population in Serbia” shows improvement compared to 2000;

however, RFs for CVDs are still highly abundant. Those data shows

that 33.6% of adults smoke, 46.5% of adults has hypertension, 18.3%

of adults are obese, and 74.3% of the population is physical

inactive [4].

Cardiovascular Diseases Risk Factors

Individual and complex approach to each patient with CVD is

necessary due to the multiple risk factors (RFs) behind CVDs.

Frequently mentioned CVD RFs are listed in the Table 1. RFs like

gender, age, physical build or race cannot be changed. However, the

list of those that can be modified is longer, and through their

modification a direct impact can be made on the development and,

more importantly, prevention of CVDs.

CVD risk assessment is simplified with a wide range of different

risk calculators shown graphically in form of charts that have been

developed to ease up the use by healthcare professionals and

individuals [6, 8]. One of the most known and frequently used is the

chart developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the

International Society for Hypertension (ISH) [6]. This tool signals

10 year risk for fatal or non-fatal outcome by including the

following RFs: gender, age, smoking, and cholesterol. In addition,

this prediction is specially adapted for patients with type 2

diabetes; one of the most important systemic disorders linked to

CVDs [9]. On the other hand, some of the newly accepted RFs like

endothelial inflammation, blood clothing, change in lipid profile

after meal, oxidative stress or endothelial function are still not

included in these CVD risk assessment tools.

Table 1. CVDs Risk Factors [6, 7]

| RISK FACTORS THAT CANNOT BE MODIFIED |

Gender

Age

Genetic predisposition

Physical build

Race |

| RISK FACTORS THAT CAN BE MODIFIED |

Smoking (passive smoking)

Low physical activity

Alcohol consumption

Diet

Obesity

Hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia

Stress |

It is believed that physical inactivity contributes to CVD

etiology with 37%. Regular physical activity reduces heart and

coronary disease risk, lowers blood pressure, contributes to body

mass maintenance, has beneficial effect on the psychological and

physical condition of a patient and helps to overcome stress [6, 7,

10]. Thus, importance of physical activity is multifold and in many

ways helps cardiovascular system, for example, increased oxygen

transport to heart muscle increases functionality and electrical

stability of the heart. In addition, physical activity has positive

effect on lipid metabolism, increases HDL cholesterol and decreases

LDL cholesterol, lowers blood pressure, reduces the occurrence of

type 2diabetes, increases insulin sensitivity and reduces

thrombocyte aggregation [10, 11]. Studies have shown that minimum an

hour of jogging per week can reduce the risk of heart disease by

42%, while 30 minutes of brisk walking a day can reduce the risk of

heart disease by about 18% and the risk of stroke by about 11% [12].

Furthermore, 30 minute walking per day is enlisted in the official

preventive guidelines for CVDs [6, 7].

Increased body mass is linked to increased blood lipids,

susceptibility to diabetes and increased blood pressure. Increased

body mass is frequently linked with low physical activity [10]. It

is believed that obesity contributes to CVD etiology with 6%. In

addition, waste circumference over 88 cm for fe-males or over 102 cm

for males is an additional CVD RF [6, 7].

Hypertension (blood pressure >140/90 mmHg) contributes to the

development of CVD by 13%. Currently, 15-37% of the adult population

worldwide has high blood pressure, while at 60 years of age this

prevalence increases to 50% of population. WHO estimates show that

45% of CVD caused deaths are associated with hypertension [13].

Moreover, WHO estimates demonstrate that 6 million people annually

die from the effects of smoking. From that number 600,000 deaths are

due to the effects of passive smoking [14]. The contribution of

smoking is 19%.

In addition, chronic emotional conditions such as stress, anxiety,

hostility, insecurity and depression are taking an increasing toll

on human health. It is believed that the risk from psychological and

social factors for developing CVD is as high as the risk from common

CVD RFs like obesity, smoking and high blood pressure [6, 10].

Studies have shown that men have a higher risk of developing CVD

than women during their childbearing age. This effect is attributed

to protecting effect of hormones. After menopause, the incidence of

coronary heart disease in men and women gradually equalizes. After

60 years of age, this ratio is 1:1. According to statistics, women

have fever CVDs diagnosed, but if they are diagnosed with any of

CVDs they die more often [6, 7, 15]. This trend was confirmed for

Croatia [2]. However, it is important to stress that both men and

premenopausal women respond positively in lipid profile and blood

pressure after introduction of the diet for people with

cardiovascular risk [16].

Furthermore, with aging human body gets more exposed to the

environment, which results in more frequent complications; heart and

blood vessels are no exception. Risk for coronary heart disease is

higher in men over age 40 and for women over age 50, especially if

they are exposed to two or more RFs [7, 10].

Some studies indicate that the tendency towards CVDs is inherited.

It is not a classical hereditary transmission of the disease; it is

more a clear correlation between the disease in parents and

manifestation in children [10].

Nutritional Treatment of Patients Diagnosed with Cardiovascular

Disease

or Risk Factors

Treating a patient with cardiovascular dis-ease (CVD) diagnosis

is very complex and it has to be individualized, and treatment

always includes change of their diet [17, 18]. Frequently, these

patients are prescribed a hypocaloric diet. If the first stage did

not result in significant change of blood parameters (usually total

cholesterol and LDL cholesterol), statins are introduced. Statins

have proven their beneficial effect in lowering LDL cholesterol and

consequently reducing cardiovascular events incidence [19].

Dietary Guidelines

It should be pointed out that the need for change in diet in

terms of preventing chronic noncommunicable diseases was acknowledge

and listed as one of the ten main goals of the Croatian nutritional

policy in 1999 [22]. Montenegro’s Ministry of Health in 2009

published „Action plan for nutrition and food safety in Montenegro

2010 – 2014“ [19], and the Republic of Serbia in 2010 published

National program for prevention [4]. As noted by Gurinović et al.

development of the national program in Serbia was necessary because

several studies on quality of nutrition in Serbia together with the

statistical data on mortality and morbidity rates due to CVDs showed

the need for more intensive preventive action [23].

WHO defined dietary goals for the prevention of CVDs that should be

met by all countries. European Heart Network [20] published

nutritional guidelines for the prevention of CVDs on the European

level. Dietary guidelines include regular physical activity (60 to

80 minutes of moderate or 30 minutes of intensive physical activity

per day), decrease in body mass index (BMI) (goal is BMI of 23

kg/m2), while mainly focusing on intake of fat, fresh fruits and

vegetables, dietary fibers and salt [21].

While planning a diet for a patient with CVD or a person at high

risk of CVDs the highest importance has fat intake, and more

importantly sources of that fat [21]. Plant based fats (oils) should

be a main fat source while planning their diet because animal fats

present significant source of saturated fatty acids (FA) [18, 24].

Earlier guidelines were focused on lower intake of cholesterol, but

today the shift has been made towards saturated FA intake [25].

Intake of saturated FA should be restricted to less than 10% of the

total energy derived from fats (overall intake of fats should be

less than 30% of the total energy intake) [21]. Also, intake of

trans-FA should be less than 2% of the total energy intake from fats

[21]. Substitution of saturated FA from animal sources with mono and

polyunsaturated FA from plant sources should lead to reduction of

blood cholesterol level [18, 26]. Official reports show that the

intake of trans-FA is far beyond the recommended with the United

Kingdom and the United States of America having the highest intakes

[6]. Another important aspect is marketing and television

advertising of sweets and fast food, which are the two food groups

that represent the main source of trans FA in daily diet.

Advertising of these products is considered a direct predictor of

trans FA intake [27].

The INTERSALT study correlates the surplus intake of salt to the

higher arterial blood pressure and increased risk of CVDs [28].

Moreover, large number of studies has shown that even slight

decrease in dietary intake of salt leads to decreased arterial blood

pressure [29]. A prospective study conducted in Finland on 2436 men

and women aged 25-64 years showed clear correlation between

increased intake of salt and increased risk of CVDs. This study

shows that salt intake over 6g/day shows 56% increased risk of

coronary disease, 36% increased risk of CVD death, and 22% increased

risk of all cause mortality [30]. Therefore, accomplishing intake of

up to 6g/day of salt is considered as an effective preventive

measure from CVDs [18, 31]. This goal for salt intake is the main

objective of the Croatian initiative CRASH [25, 32], and the

Strategic plan for prevention and control of noncommunicable

diseases in the Republic of Serbia [33]. Despite large number of

national programs targeting lower intake of salt, salt intake

remains elevated around the world. The highest intake of salt was

found in Hungary of 17 g/day/person, with excessive 12 g [6].

Alcohol consumption in high amounts is correlated to increased death

rate, especially due to CVDs [6]. Still, results are inconsistent.

Large number of studies showed relatively small risk of CVDs for

moderate alcohol consumption [18, 34-36]. However, alcohol also

shows some positive effects like increases level of HDL cholesterol

and lowers thrombocyte activity [34, 35], which directly reduces the

risk of thrombosis that lies behind the etiology of CVDs.

Developing a diet plan for a patient with CVD usually includes

consideration of one of the two approaches. The first one is the

Dietary Ap-proaches to Stop Hypertension, or so called the DASH diet

[37]. This approach is based on a low intake of saturated fats and

sodium with increased intake of fruits and vegetables combined with

low fat dairy products [37]. The other approach is the Mediterranean

diet, which was confirmed by the Lyon Diet Heart Study and the

PREDIMED study to have direct correlation to lower mortality rate,

especially due to CVDs [18, 38, 39].

Mediterranean Diet – The Definition

Keys presented the first Mediterranean diet (MD) definition. He

proved, for the first time, health benefits of the MD in a research

encompassing more than 12 700 people from seven Mediterranean

countries [40]. In Croatia, several studies dealing with the dietary

habits of inhabitants on isolated island have been conducted [41].

All showed that even though the diet of islanders is (eg. Vis, Mljet)

fundamentally Mediterranean, there is a shift that can be noticed.

This shift is seen in increased consumption of industrial products,

sugar and read meat, which coincides with lower consumption of fish,

fruits and vegetables

[41]. Although in their diets there is some traditional MD present

many islanders show unfavourable shift in their dietary patterns

[42]. These findings are in accordance with the increased problems

related to CVDs among researched islanders [41].

Even though there is no such thing as one MD, some characteristics

are shared. These are: a) high intake of fats (more than 40% of

total energy intake), mostly from olive oil; b) high intake of

wholegrain, fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts; c) moderate to

high consumption of fish; d) moderate to low consumption of white

meat (poultry or rabbit meat) and dairy products, mostly yoghurt or

fresh cheese; e) low consumption of red meat and meat products; f)

moderate consumption of red wine with meal [43, 44]. The last MD

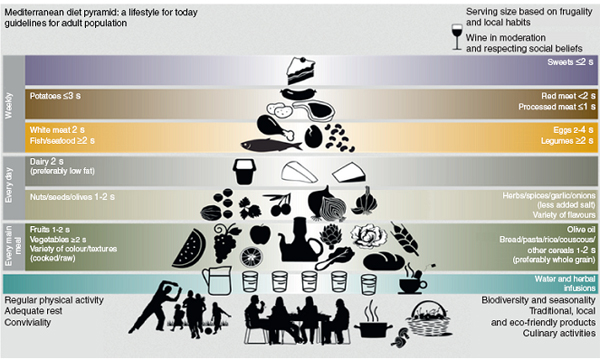

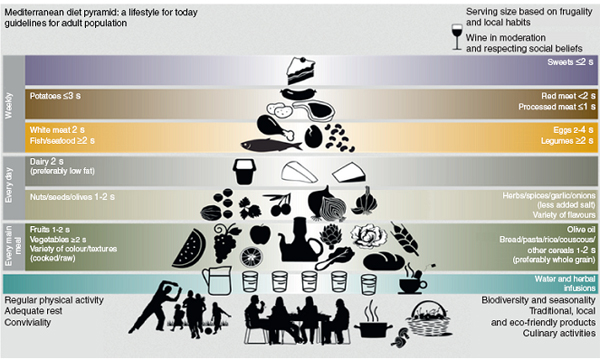

pyramid (Picture 2) includes two main changes related to consumption

of cereals and dairy products. By and large, these relate to intake

of wholegrain and low fat dairy products. In addition, physical

activity, socialization and psychosocial aspects related to dining

with friends and family have been added to the pyramid [43].

Picture 2 The Mediterranean diet pyramid [43]

Mediterranean Diet’s Characteristics

Discussions on the MD usually imply that the MD is a diet rich in

fats. However, there are different types of the MD. Some are high in

fats (Greece) and other are quite low in fats (South Italy, South

France) [40, 45]. For example, the Lyon study researched a low fat

content [10, 40] with the main fat source being canola oil margarine

not olive oil [45].

Beneficial effect on cardiovascular health olive oil owns to its FA

profile. Mono and polyunsaturated FA reduce blood cholesterol level

and risk of heart diseases when they substitute one portion of

saturated FA in the diet. The most common FA from the family of

monounsaturated FA is oleic acid, the main FA of olive oil [47]. Due

to its high content in olive oil and other antioxidants, consumption

of olive oil reduces LDL cholesterol simultaneously affecting HDL

cholesterol. Additionally, this composition of olive oil prevents

oxidation of LDL cholesterol [47, 48]. Also, olive oil contains

other components out of which plant sterols, and beta-sitosterols

are the most important in reduction of cholesterol levels [25, 47].

Therefore, olive oil has several protective mechanisms on

atherosclerosis.

Fish is a food group with almost ideal nutritional profile. They are

rich in essential FA, ome-ga-3 FA and proteins [24, 43]. Two main

omega-3 FA in fish are eicosapentaenic (EPA) and docohex-aenoic

acids (DHA). It has been proved that supplementation of 2 to 4 g of

omega-3 FA/day in patients with increased triglycerides will reduce

their triglycerides by 25 to 30%. Additionally, 1 g/day of omega-3

FA given to patients after recovered myocardial infarction

significantly reduces overall mortality and risk of sudden death due

to arrhythmia [46].

Studies have shown that the MD long-term leads to weight loss,

change in BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting blood

glucose level, total cholesterol and endothelial inflammation

indicator and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) [45, 49].

The largest hospital in Croatia, University Hospital Centre Zagreb

provides its patients with hypolipemic MD since 2011 [50].

One of the main additional characteristics of the MD is moderate

consumption of red wine [43]. Phenols from red wine, especially

resveratrol (also present in red grapes), decrease oxidation of LDL

cholesterol, causatively affecting atherogenicity, act as an

anti-aggregation, and antiinflammatory agents, and diminish

thrombocyte aggregation, contributing to possible anti

atherosclerotic effects. Significant part of wine’s protective

effects can be attributed to HDL cholesterol increase [25, 35, 51].

Mediterranean Diet and Health Benefits

After publication of the results of the Lyon Diet Heart Study

(Lyon) [40], number of studies reported on various health benefits

of the MD. In 2003 Trichopoulou et al. published the first modern

epidemiological study that examined impact of the MD on different

health aspect [52]. This prospective follow-up study encompassed 22

043 adult Greeks, and was observing their diet with so called

Mediterranean score. Study found that the higher the score was, the

lower mortality rate from CVDs was. Final data showed that mortality

rate from CVDs and cancers was inversely correlated to higher MD

compliance [52], and the study confirmed earlier findings from the

Lyon study [10, 40]. Higher compliance to the MD correlates to the

lower prevalence of obesity [53], which was also confirmed by

Croatian studies [41, 42]. Meta-analysis published in 2010 summed-up

the whole inverse relation between the MD, CVDs and overall

mortality [39]. Additionally, meta-analysis pub-lished in 2011

showed that the MD has higher protective effect on health than a low

fat diet [49].

The last large prospective study conducted in Spain, the PREDIMED

study, have shown that adoption of the MD leads to 30% reduction in

complications due to hearth diseases, and 40% lower risk of heart

attack, which was based on a 5 year follow-up [54]. In addition,

this study confirmed earlier findings; the importance in primary

prevention from the Lyon study [10, 40], epidemiologic significance

from the aspects of morbidity and mortality [39, 52] from CVDs, as

well as from cancers, dementia, and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease

[55-57]. Furthermore, Skarupski et al. [58] showed that dietary

pattern that is more in accordance to the MD (based on MedDietScore

principle) shows potential in reducing depression among people of 65

years and older.

Recently, more emphasis is put on possibilities to modify the MD for

non-Mediterranean populations, seeing it as a possible solution for

noncommunicable diseases [59]. This is due to a large number of

prospective studies performed in the non-Mediterranean countries

that, besides already determined effect of the MD, show MD’s

potential to protect from premature death [60-64], and

cerebrovascular diseases [65].

CONCLUSION

For years, Mediterranean diet is on the top of scientific

interest. The reason lies in proven correlation with CVDs

prevention, and causatively lower mortality and morbidity due to

CVDs. Moreover, this effect was found for other noncommunicable

chronic diseases, from cancers to dementia. The Mediterranean diet

is not just a specific dietary regime; it represents a way of life.

Characteristic combinations of foods, with some specifics between

Mediterranean countries make it plain and complicated at the same

time. Undoubtedly, the Mediterranean diet will keep on positioning

itself as one of the possible solutions to global issues related to

CVDs.

LITERATURE

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases, Fact

sheet No 317. World Health Organization, 2013. Available from:

http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en

- Hrvatski zavod za javno zdravstvo. Umrle osobe u Hrvatskoj u

2011. godini. Hrvatski zavod za javno zdravstvo, Služba za javno

zdravstvo, Zagreb, 2012.

- Ministarstvo zdravlaj Crne Gore. Akcioni plan za ishranu i

bezbjednost hrane Crne Gore 2010-2014. Ministarstvo zdravlja

Crne Gore, Podgorica, 2009.

- Službeni glasnik Republike Srbije. Uredba o nacionalnom

programu prevencije, lečenja i kontrole kardiovaskularnih

bolesti do 2020. godine. Službeni glasnik Republike Srbije br.

11/2010, Beograd, 2010.

- Institut za javno zdravlje Srbije „Dr. Milan Jovanović

Batut“. Zdravlje stanovnika Srbije – analitička studija 1997-

2007. Institut za javno zdravlje Srbije, Beograd, 2008.

- World Health Organization. Global Atlas on cardiovascular

disease prevention and control. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 2011.

- American Heart Association (AHA). Understand your risk of

heart attack. 2012. Available from:

www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartAttack/

UnderstandYourRiskofHeartAttack/Understand-Your-Risk-of-Heart-Attack_UCM_002040_Article.jsp

- Singh M, Lennon RJ, Holmes DR Jr, Bell MR, Rihal CS.

Correlates of procedural complications and a simple integer risk

score for percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol

2002; 40(3): 387-93.

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 6th

edition. IDF; 2013.

- De Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, Delaye

J, Mamelle N. Mediterrranean Diet, Traditional Risk Factors, and

the Rate of Cardiovascular Complications After Myocardial

Infarction: Final Report of the Lyon Diet Study. Circulation

1999; 99(6): 779-85.

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM,

Strath SJ et al. Compendium of physical activities: An update of

activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;

32(9 suppl): S498-504.

- Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of

physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ 2006; 174(6): 801-9.

- World Health Organization. A global brief on hypertension.

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- World Health Organization. WHO Update on smoking. Fact sheet

No 339. World Health Organization, 2013. Available from:

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/

- Demarin V, Lisak M, Morović S. Mediterranean Diet in Healthy

Lifestyle and Prevention of Stroke. Acta Clin Croat 2011; 50(1):

67-77.

- Bédard A, Riverin M, Dodin S, Corneau L, Lemieux S. Sex

differences in the impact of the Mediterranean diet on

cardiovascular risk profile. Brit J Nutr 2012; 108: 1428-34.

- Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL,

Jameson JL et al. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine,

17th edition. New York: Mc-Graw Hill Medical; 2008.

- Verschuren WMM. Diet and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr

Cardiol Rep 2012; 14: 701-8.

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' Collaborators. Efficacy and

safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective

meta-analysis of data from 90 056 participants in 14 randomised

trials of statins. Lancet 2005; 366: 1267-78.

- Haveman-Nies A, de Groot LP, Burema J, Cruz JA, Osler M, van

Staveren WA. Dietary quality and lifestyle factors in relation

to 10-year mortality in older Europeans: the SENECA study. Am J

Epidemiol 2002; 156: 962-8.

- Bhupathiraju SN, Tucker KL. Coronary heart disease

prevention: Nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns. Clinica

Chimica Acta 2011; 412(17-18): 1493-514.

- Ministarstvo zdravstva i Hrvatski zavod za javno

zdravstvo.Hrvatska prehrambena politika. Hrvatski zavod za javno

zdravstvo, Zagreb, 1999.

- Gurinović M, Ristić-Medić D, Vučić V, Milešević J,

Konić-Ristić A, Glibetić M. Ishrana i kardiovaskularne bolesti.

Acta Clinica 2013;13(1):156-68.

- Vrca Botica M, Pavlić Renar I i sur. Šećerna bolest u

odraslih. Zagreb: Školska knjiga; 2012.

- Reiner Ž. Uloga prehrane u prevenciji i terapiji

kardiovaskularnih bolesnika. Medicus 2008; 17: 93-103.

- Vaccarino V. The Mediterranean Diet in Cardiovascular

Disease. U Trovato GM urednik. The Mediterranean Diet: A

resources for Medicine, An opportunity for Italy. Italija:

Dietamed, 2010.

- Raine KD, Lobstein T, Landon J, Potvin Kent M, Pellerin S,

Caulfield T et al. Restricting marketing to children: Consensus

on policy interventions to address obesity. Journal of Public

Health Policy 2013; 34(2): 239-53.

- Stamler J. The INTERSALT study: background, methods,

findings, and implications. Am J Clin Nutr 1997; 65(suppl):

626S-42S.

- Dumler F. Dietary sodium intake and arterial blood pressure.

J Ren Nutr 2009;19:57-60.

- Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P, Rastenyte D, Moltchanov V,

Tanskanen A, Pietinen P et al. Urinary sodium excretion and

cardiovascular mortality in Finland: a prospective study. Lancet

2001; 357: 848-51.

- Asaria P, Chisholm D, Ezzati M, Beaglehole R. Chronic

disease prevention:Health effects and financial costs of

strategies to reduct salt intake and control tobacco use. Lancet

2007; 370: 2044-53.

- Jelaković B, Kaić-Rak A, Miličić D, Premužić V, Skupnjak B,

Reiner Ž. Manje soli – više zdravlja. Hrvatska inicijativa za

smanjenje prekomjernog unosa kuhinjske soli (CRASH). Liječnički

vijesnik 2009; 131: 87-92.

- Ministarstvo zdravlja Republike Srbije. Strategija za

prevenciju i kontrolu hroničnih nezaraznih bolesti Republike

Srbije. Awailable from:

http://www.minzdravlja.info/downloads/Zakoni/Strategije/Strategi-ja

Za Prevenciju I Kontrolu Hronicnih Nezaraznih Bolesti.pdf

- Costanzo S, Di Castelnuovo A, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de

Gaetano G. Alcohol Consumption and Mortality in Patients With

Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis. J AM College Cardiol

2010; 55(13): 1339-47.

- Klatsky AL. Alcohol and cardiovascular health. Physiology &

Behavior 2010; 100(1): 76-81.

- Beulens JWJA, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Visseren FLJ, Grobbee DE,

van der Graaf Y. Alcohol consumption and risk of recurrent

cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with clinically

manifest vascular disease and diabetes mellitus: The Second

Manifestations of ARTerial (SMART) disease study.

Atherosclerosis 2010; 12(1): 281-6.

- Appel LJ, Thomas MPH, Moore J, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM,

Svetkey LP et al. A clinical trial of the effect of dietary

patterns and blood pressure management. N Eng J Med 1997; 336:

1117-24.

- Tracy SW. Something new under the sun? The Mediterranean

diet and cardiovascular health. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(14):

1274-6.

- Sofi F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Accruing evidence on

benefits of adherence to theMediterranean diet on health: an

updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr

2010; 92(5): 1189-96.

- De Lorgeril M. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular

Disease: Historical Perspective and Latest Evidence. Curr

Atheroscler Rep 2013; 15: 370.

- Missoni S. Nutritional Habits of Croatian Island Populations

– Recent Insights. Coll. Antropol 2012; 36(4): 1139-1142.

- Sahay RD, Couch SC, Missoni S, Sujoldžić A, Novokmet N,

Duraković Z et al. Dietary Patterns in Adults from an Adriatic

Island of Croatia and Their Associations with Metabolic Syndrome

and Its Components. Coll Antropol 2013; 37(2): 335-42.

- Aros F, Estruch R. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular

Prevention. Rev Esp Cardiol 2013;66(10):771-4.

- Schroder H. Protective mechanism of the Mediterranean diet

in obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Nutr Biochem 2007; 18(3):

149-60.

- Di Daniele N, Petramala L, Di Renzo L, Sarlo F, Della Rocca

DG, Rizzo M et al. Body composition changes and cardiometabolic

benefits of a balanced Italian Mediterranean Diet in obese

patients with metabolic syndrome. Acta Diabetol 2013; 50:

409-16.

- Delgado-Lista J, Perez-Caballero AI, Perez-Martinez P,

Garcia-Rios A, Lopez-Miranda J, Perez-Jimenez F. Mediterranean

Diet and Cardiovascular Risk. U: Gasparyan AY urednik.

Cardiovascular Risk Factors. InTech, 2012.

- Farràs M, Valls RM, Fernández-Castillejo S, Giralt M, Solà

R, Subirana I et al. Olive oil polyphenols enhance the

expression of cholesterol efflux related genes in vivo in

humans. A randomized controlled trial. J Nutr Biochem 2013;

24(7): 1334-9.

- Widmer RJ, Freund MA, Flammer AJ, Sexton J, Lennon R, Romani

A et al. Beneficial effects of polyphenolrich olive oil in

patients with early atherosclerosis. Eur J Nutr 2013; 52:

1223-31.

- Nordmann AJ, Suter-Zimmermann K, Bucher HC, Shai I, Tuttle

KR, Estruch R et al. Meta-Analysis Comparing Mediterranean to

Low-Fat Diets for Modification of Cardiovascular Risk Factors.

Am J Med 2011; 124: 841-51.

- Krznarić ž, Vranešić Bender D, Pavić E. Prehrana bolesnika s

metaboličkim sindromom. MEDIX 2011; 17(97): 156-9.

- Quiñones M, Miguel M, Aleixandre A. Beneficial effects of

polyphenols on cardiovascular disease. Pharmacological Research

2013; 68(1): 125-31.

- Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D.

Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Survival in a Greek

population. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2599-608.

- Bonaccio M, Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, De Lucia F,

Olivieri M, Donati MB et al. Nutrition knowledge is associated

with higher adherence to Mediterranean diet and lower prevalence

of obesity. Results from the Moli-sani study. Appetite 2013; 68:

139-46.

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, Covas M-I, Corella D,

Arós F et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with

a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(14): 1279-1190.

- Shah, R. The role of nutrition and diet in Alzheimer

disease: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013; 14(6):

398-402.

- Lourida I, Soni M, Thompson-Coon J, Purandare N, Lang IA,

Ukoumunne OC et al. Mediterranean diet, cognitive function, and

dementia: a systematic review. Epidemiology 2013; 24(4): 479-89.

- Sofi F, Macchi C, Casini A. Mediterranean Diet and

Minimizing Neurodegeneration. Curr Nutr Rep 2013;2:75-80.

- Skarupski KA, Tangley CC, Li H, Evans DA, Morris MC.

Mediterranean diet and depressive symptoms among older adults

over time. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 2013; 17(5):

441-5.

- Hoffman R, Gerber M. Evaluating and adapting the

Mediterranean diet for non-Mediterranean populations: A critical

appraisal. Nutr Rev 2013; 71(9): 573-84.

- Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Nooyens AC, Kromhout D, Spijkerman AM,

Beulens JW, van der Schouw et al. Mediterranean style diet and

12-year incidence of cardiovascular diseases: the EPICNL cohort

study. PLoS One 2012; 7(9): e45458.

- Martínez-González MA, Guillén-Grima F, De Irala J,

Ruíz-Canela M, Bes-Rastrollo M, Beunza JJ et al. The

Mediterranean diet is associated with a reduction in premature

mortality among middle-aged adults. J Nutr 2012; 142(9) :1672-8.

- Gardener H, Wright CB, Gu Y, Demmer RT, Boden-Albala B,

Elkind MS et al. Mediterranean-style diet and risk of ischemic

stroke, myocardial infarction, and vascular death: the Northern

Manhattan Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 94(6): 1458-64.

- Tognon G, Lissner L, Sæbye D, Walker KZ, Heitmann BL. The

Mediterranean diet in relation to mortality and CVD: a Danish

cohort study. Br J Nutr 2013; 3: 1-9.

- Hodge AM, English DR, Itsiopoulos C, O'Dea K, Giles GG. Does

a Mediterranean diet reduce the mortality risk associated with

diabetes: evidence from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort

Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011; 21(9): 733-9.

- Misirli G, Benetou V, Lagiou P, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D,

Trichopoulou A. Relation of the traditional Mediterranean diet

to cerebrovascular disease in a Mediterranean population. Am J

Epidemiol 2012; 176(12): 1185-92.

|

|

|

|