| |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

Acute bacterial meningitis (ABM) is an infectious disease with

significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. Mortality in

untreated patients is up to 50%, in treated 8-15%. Having gone

through the disease, 10-20% of patients remain with permanent

neurological and mental disorders. [1]. Etiological agents depend on

age and geographical area. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria

meningitidis are the most common causes of ABM in adults [2].

Hemophilus influenzae is the cause of ABM at all ages, more common

in the population of children up to 5 years of age before the

mandatory vaccine [3]. The etiological diagnosis requries isolation

of the causative agent from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), but

meningism is possible with the presence of bacteria in the blood

[4]. Predisposing factors for the development of ABM include head

trauma, sinusitis, otitis, pharyngitis, pneumonia, but also other

immunodeficient conditions such as alcoholism, splenectomy,

neurological and hematological diseases.

THE AIM of this study was to analyze the epidemiological

characteristics, etiology, risk factors, clinical course and

prognosis of acute bacterial meningitis in the adult population in

the Zlatibor district.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The research included patients treated at the Department of

Infectious Diseases and the Intensive Care Unit of the General

Hospital Uzice, in the period from 1st. January 2009 to 31st

December 2019. Demographic data, risk factors, hematological and

biochemical data from blood and CSF, cytological findings of CSF

were collected retrospectively. The clinical course and outcome of

the disease were analyzed, too.

Hematological and biochemical analyses from blood and CSF were

performed by standard methods used in the Republic of Serbia. The

etiological diagnosis was made by identifying the causative agent

from CSF culture or blood, when CSF culture was negative or

unavailable. Samples of CSF were cultured on blood agar plates

containing 5% sheep blood and on chocolate agar, incubated in carbon

dioxide for 24 - 48 h at 37° C. Isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae

and Neisseriae meningitidis were preliminarily identified based on

typical colonial prospects, Gram staining and optochin test for

Streptococcus pneumoniae. The Vitek system (bioMérieux, Marcy

l'Etoile, France) was used for the final identification and testing

of antibiotic susceptibility. The minimum inhibitory concentration

test was performed by the E test, according to CLSI guidelines [5].

All patients underwent ophthalmic examination of the fundus and/or

computed tomography (CT) scan of the endocranium.

Patients with tuberculous meningitis were excluded from the study.

The outcome of the disease was assessed on the basis of the Glasgow

Coma Scale with the following values:

score 1 - death; score 2 - inability of patients to interact with

the environment; score 3 - inability of the patient to live

independently, but there is an interaction with the environment;

score 4 - ability to live independently with incapacity for work;

score 5 - working ability. The favorable outcome of the disease was

defined by a score of 5, while scores 1 to 4 were marked as an

unfavorable outcome [6].

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences SPSS (version 16.0) was

used for statistical analysis. A significant difference was

represented by P <0.05.

RESULTS

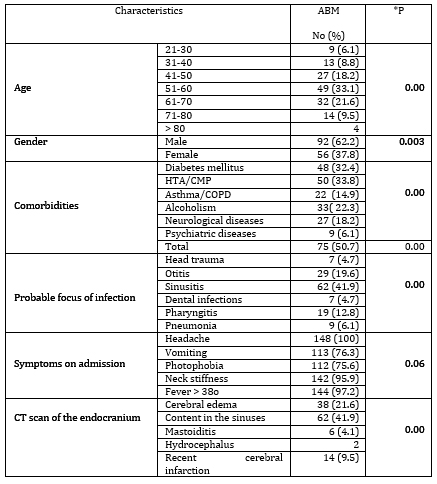

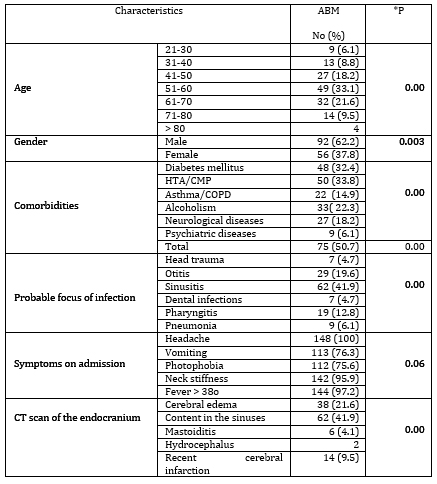

A total of 148 patients with ABM was examined, 92 men and 56

women, aged 22 to 84 years of age, averaged 55.8 +/- 13.1.

A significant number of patients had comorbidities. A third of

patients had diabetes and heart disease, 22.3% consumed alcohol

excessively. The origin of the infection could be assumed in 88.5%

of the patients. Sinusitis was significantly the most common at

41.9%. In 19.6% of patients, ABM was preceded by ear inflammation,

in 12.8% by pharyngitis. All patients experienced headache on

admission, 97.2% had fever, and 95.9% had neck stiffness during head

anteflexion. Vomiting and photophobia were present in 76.3% and

75.6%, respectively. There was no statistically significant

difference between the presence of these symptoms.

All patients underwent ophthalmologic examination of the fundus. CT

scan of the endocranium was performed in 82.4%. Pathological finding

in the sinus cavities was significantly the most common in 41.9%.

Epidemiological characteristics, comorbidities, possible focus of

infection, symptoms and findings of CT scan of the endocranium are

shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Epidemiological parameters, comorbidities,

focus of infection, symptoms and CT scan finding in patients with

ABM

*P - statistical significance for samples ≥ 5

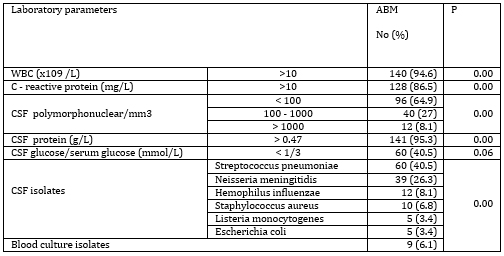

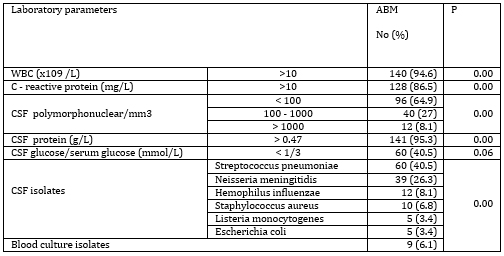

All patients underwent lumbar puncture. The number of

polymorphonuclear leukocytes was significantly up to 100/mm3. In a

significant majority of patients (95.3%), CSF proteins were

elevated, while CSF/blood glucose index was reduced in 40.5% of

subjects. The value of protein in the CSF was from 0.22 - 6.1 g / L,

on average 2.8 +/- 2.2 g / L.

The most common causes of ABM were Streptococcus pneumoniae and

Neisseria meningitidis, in 40.5% and 26.3%, respectively. Other

pathogens were significantly rarer.

Serum biochemical parameters of bacterial infection, leukocytosis

and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level, were observed in a

significant number of patients, 94.6% and 86.5%, respectively. The

leukocyte count ranged from 5.6 to 16.2x109 / L, averaging

12.4x109/L. The CRP value range was 3.4 - 122 mg/L, averaging 34.1

+/- 45.2 mg / L.

Biochemical findings from blood and cerebrospinal fluid, cytological

findings of cerebrospinal fluid and etiological causes of acute

bacterial meningitis are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Biochemical findings of blood and CSF,

cytological findings of CSF and etiological agents of ABM

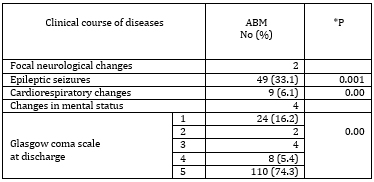

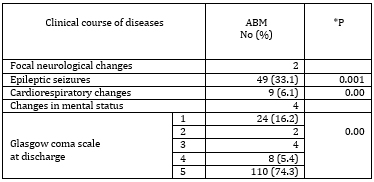

The clinical course was favorable in a significant

majority (74.3%) of the patients. One third of patients had

epileptic seizures. In 24 (16.2%) patients the disease ended

lethally (Table 3).

Table 3. Clinical course and outcome of patients

with ABM

*P - statistical significance for samples ≥ 5

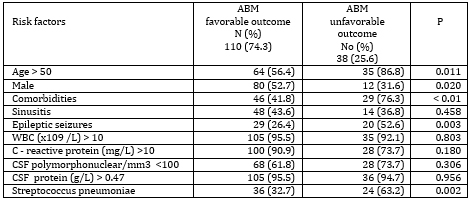

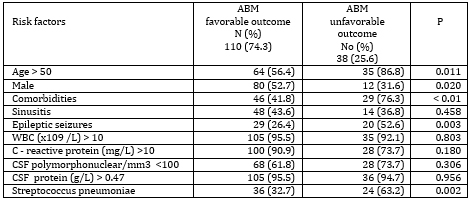

Risk factors for unfavorable disease outcome were further

examined (Table 4)

Table 4. Risk factors for unfavorable outcome of

ABM

Significant factors for the unfavorable outcome of acute

bacterial meningitis were the presence of comorbidities,

Streptococcus pneumoniae as the cause of the disease, the occurrence

of epileptic seizures, age over 50 and male gender.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of the causes of ABM has indicated differences depending

on a wide range of examined age groups in recent years [7].The most

common causes are Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitis

in adult population, while in children the most common are

Streptococcus agalactiae, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes

[8]. Our study included adult population and the frequency of

individual pathogens corresponds to the above conclusion of other

researchers. Haemophilus influenzae is a childhood pathogen,

significantly rarer after the vaccine became mandatory [8]. In our

study, it was present in 8.1%, which is expected given that it is

the most common colonizer of the respiratory tract mucosa, and

especially common in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease [9].

Demographic data showed that men got sick more often, which

corresponds to the finding of Diaz and colleagues who proved that

men with ABM have more frequent head trauma and excessive alcohol

consumption as risk factors [10]. The main risk factor of our

patients was hypertension/cardiomyopathy. This can be explained by

older age of the patients. Diabetes mellitus was the second most

important risk factor. Diabetes leads to changes in body's immune

defenses. The function of polymorphonuclear leukocytes is reduced,

especially when acidosis is also present. Leukocyte adhesion,

chemotaxis, and phagocytosis were also altered and antioxidant

bactericidal systems were weakened [11].

Inflammation of the sinuses and ear are more common possible sources

of infection in our patients, unlike other studies [12]. This result

can be explained by the proven high percentage of bacterial

sinusitis in the adult population [13, 14]. This finding is

supported by the finding of CT scan, which most often indicated a

pathological process in the sinuses. In addition to headache, neck

stiffness and fever with a change in mental status were the most

common symptoms of both our study and others. [12]. The clinical

course of our patients was accompanied by the occurrence of

epileptic seizures in one third of patients. CNS infections as a

cause of epilepsy are present in a quarter of patients with ABM

[15]. Epileptic seizures have been shown to correlate with lower

sugar values and higher protein values in CSF [16]. Risk factors for

subsequent unprovoked seizures include focal discharge, sharp

electroencephalographic waves, and initial CSF glucose <20 mg / dl

[17]. The cytological finding of CSF with pleocytosis with the

dominance of polynuclear neutrophils is a standard finding in ABM,

which corresponds to our results. Elevated protein values present in

a significant majority of our patients are expected findings for

bacterial meningitis, although there are data in literature that

1-10% of patients with ABM do not have elevated CSF protein [18].

The value of glucose in CSF was reduced in 40% of our patients. This

is consistent with other data describing less than 50% of patients

with similar findings. The results indicate the unreliability of

this parameter in the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis [19].

The serum parameter of inflammation, C - reactive protein, was

elevated in a large percentage of our patients. Browver and

coauthors pointed out the unreliability of CRP values in the

diagnosis of ABM [20].

The unfavorable clinical course in our patients is smaller than

described [12]. The most common cause of death is Streptococcus

pneumoniae. The most significant risk factors are advanced age and

the presence of comorbidities, which corresponds to the findings of

other authors [12]. Our finding is partly consistent with the

findings of other authors who mention the most common age over 65

years [12]. Respondents from Nis authors were mostly of the same age

group as ours, with researchers noting that older people often have

more sparse symptoms at the beginning of the disease [21]. The

authors explain the small percentage of bacterial isolates from CSTs

by using antibiotic therapy before taking CSTs. This can delay the

diagnosis and adversely affect the further clinical course and

outcome of the disease. Interesting are the conclusions of the

authors who examined the influence of climatic factors on the

occurrence of bacterial meningitis and obtained a positive

correlation with the occurrence of wind and fog, and a negative

correlation with insolation [22]. It can be assumed that it would be

useful to analyze climate data in our patients as well.

CONCLUSION

The expected causative agent of a disease in a patient population

is of great importance for each geographical area. The most common

cause of acute bacterial meningitis in the adult population of

Zlatibor district is Streptococcus pneumoniae, in 40.5% of patients,

which is also the most common cause of adverse disease outcomes. The

second most common is Neisseria meningitidis (26.3%). ABM is most

common in men in their sixth decade of life who have comorbidities.

The occurrence of epileptic seizures during ABM is also a risk

factor of unfavorable outcomes of disease. The sourse of ABM is most

often in the sinuses or ear, so timely treatment of these infections

is an important preventive measure. Since there is a vaccine

prophylaxis for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis,

it is necessary to recommend this preventive measure to the elderly,

especially those who have comorbidities.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization (WHO). Meningococcal meningitis:

Fact sheet 2017 [updated December 2017; cited 2017 November 9].

Dostupno na:

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs141/en/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Bacterial

Meningitis 2017 [updated January 25, 2017]. Dostupno na:

https://www.cdc.gov/meningitis/bacterial.html

- World Health Organization (WHO). Haemophilus influenzae type

b (Hib) Vaccination Position Paper July 2013. Releve

epidemiologique hebdomadaire. 2013; 88 (Suppl 39): 413-26.

- McGill F, Heyderman RS, Michael BD, et al. The UK joint

specialist societies guideline on the diagnosis and management

of acute meningitis and meningococcal sepsis in immunocompetent

adults. J Infect. 2016; 72: 405–38.

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing,

Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters,

2011 EUCAST Version 1.3. Available from:

http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/

- Jennett B, Teasdale G. Management of head injuries. 2nd ed.

Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 1981.

- Oordt-Speets AM, Bolijn R, van Hoorn RC, Bhavsar A, Kyaw MH.

Global etiology of bacterial meningitis: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018;13(6):e0198772. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198772

- Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR, van de Beek D. Epidemiology,

diagnosis, and antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial

meningitis. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2010; 23 (Suppl 3):

467-92.

- Murphy TF, Brauer AL, Sethi S, Kilian M, Cai X, Lesse AJ.

Haemophilus haemolyticus: a human respiratory tract commensal to

be distinguished from Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis.

2007; 195 (Suppl 1): 81-9.

- Yerramilli A, Mangapati P, Prabhakar S, Sirimulla H,

Shravani Vanam S, Voora Y. A study on the clinical outcomes and

management of meningitis at a tertiary care centre. Neurol

India. 2017; 65 (Suppl 5):1006-12.

- Joshi N, Gregory M. Caputo, Michael R. Weitekamp, A.W.

Karchmer. Infections in patients with diabetes mellitus.N Eng J

Med. 1999; 341: 1906-12.

- Beek D, Gans J, Spanjaard L, Weisfelt M, Reitsma JB,

Vermeulen M. Clinical Features and Prognostic Factors in Adults

with Bacterial Meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2004; 351: 1849-59.

- Sami AS, Scadding GK, Howarth P. A UK Community-Based Survey

on the Prevalence of Rhinosinusitis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018;43 (Suppl

1): 76-89.

- Bhattacharyya N, Gilani S. Prevalence of Potential Adult

Chronic Rhinosinusitis Symptoms in the United States.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.2018; 159 (Suppl 3): 522-5.

- Preux PM, Druet-Cabanac M. Epidemiology and etiology of

epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Neurol 2005; 4: 21-31.

- Chang CJ, Chang HW, Chang WN, Huang LT, Huang SC, Chang YC,

Hung PL, Chang CS, Chuang YC, Huang CR, Tsai NW, Tsui HW, Wang

KW, Lu CH. Seizures complicating infantile and child-hood

bacterial meningitis. Pediatr Neurol 2004; 31: 165-71.

- Pomeroy SL, Holmes SJ, Dodge PR, Feigin RD. Seizures and

other neurologic sequelae of bacterial meningitis in children.

NEngJ Med. 1990; 323: 1651-7.

- Viallon A, Botelho-Nevers E, Zeni F. Clinical decision rules

for acute bacterial meningitis: current insights. Open Access

Emergency Medicine 2016; 8: 7-16.

- Durand ML, Calderwood SB, Weber DJ, et al. Acute bacterial

menin¬gitis in adults. A review of 493 episodes. N Engl J Med.

1993; 328 (Suppl 1): 21-8.

- Brouwer MC, Thwaites GE, Tunkel AR, Van De Beek D. Dilemmas

in the diagnosis of acute community-acquired bacterial

meningitis. Lancet. 2012; 380 (9854): 1684-92.

- Ranković A, Vrbić M, Jovanović M, Popović-Dragonjić L,

Đorđević-Spasić M. Meningeal syndrome in the practice of

Infectious diseases. Acta Medica Medianae 2017; 56(2): 32-7.

- Janković Lj, Pantović V, Damjanov V. Korelacija između klime

i bakterijskog meningitisa. Medicus 2006;7 (1):29-31.

|

|

|

|