| |

|

|

Introduction According to experiences from previous

epidemics and pandemics of infectious diseases around the world,

restrictive epidemiological measures in the form of restriction of

movement, social isolation and distancing and prevention of physical

contact, although effective in reducing transmission and infection

rates, cause a state of increased collective psychological tension,

fear (1-3). The most stressful aspects of such public health crises

are their unpredictability, as well as uncertainty regarding disease

control and assessment of the degree and severity of health risks.

Uncertainty, constant challenges and stress in crisis situations

such as epidemics and pandemics of infectious diseases can

negatively affect mental disorders by inducing them and complicating

their course and outcome (4).

The SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic itself as well as all epidemiological

measures introduced to curb it pose a psychological burden on the

population, disrupting the personal, family and social functioning

of the individual, especially in vulnerable social groups such as

psychiatric patients, margins of society (5).

The negative consequences of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic on the

mental health of the population around the world are already

visible. According to expert estimates, they will reach their peak

in the coming period and will very likely survive the current

pandemic for a long time (6). Research by Brooks et al points out

that periods of self-isolation, restrictions on social contacts and

quarantine, even shorter than 10 days, can have long-term

consequences with the presence of mental disorders up to 3 years

later (7).

Studies have appeared primarily by Chinese authors that note the

negative impact of the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic on mental health,

and especially on the growing anxiety and depression among Chinese

health workers, in the general population, but also in the group of

psychiatric patients.

Therefore, this study aims to compare the mental health effects of

the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic on patients with psychiatric illness

compared to previously mentally healthy individuals, and thus to

contribute to the general knowledge of the overall consequences of

SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic.

Material and methods

The study is designed as a cross-sectional study. It was

conducted during May and June 2020 at the end and immediately after

the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic in Serbia.

Participants were divided into two groups - a clinical group of

patients with mental disorders and a control group composed of the

general population who had no previous mental disorders.

Participants for the clinical group were recruited within the

outpatient-specialist psychiatric service, and for the control

group, students filled out the same questionnaire in online form.

The basic criterion for inclusion of subjects in the clinical group

was the presence of a mental disorder from before, while the control

group was composed of selected subjects without pre-existing mental

disorder. Data were collected through a specially designed

questionnaire for self-assessment of the existence and intensity of

mental symptoms in respondents. The questionnaire first contained a

set of general questions about sociodemographic characteristics and

the previous existence of a psychiatric disorder. Then, questions

were created about the existence of fear, mental tension,

irritability, anxiety, the appearance of panic attacks, and the

overall level of anxiety and feelings of uncertainty. Then there

follows a series of questions that aim to record the symptoms from

the depressive spectrum, especially with reference to anhedonia,

loss of emotions, pleasure, the appearance of feelings of sadness

and depression. Then there is the question of sleep and sleep

problems as the symptom that is most indicative of the appearance of

a certain psychological distress. There are also direct questions

about suicidal thoughts and intentions. The main reason for the

generalized feeling of fear and uncertainty are questions about the

fear of losing a job, poverty and misery, and a possible decline in

the quality of life due to material difficulties that arose during

the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic. Also, the unavailability of adequate

health care due to the state of emergency and restrictive measures

was stated as a contributing factor of uncertainty and concern. As a

form of self-help and human defense mechanisms against the current

stressful situation, the need for the use / increased use / abuse of

psychopharmaceuticals is assumed, and on the other hand, man's

attempt to improve his lifestyle and overcome the crisis by his own

efforts and struggles. The SPSS for Windows 20 program, which runs

under the Microsoft Windows environment, was used for data

processing. The results are shown tabularly.

In order to compare the group of respondents with mental disorders

and those without a diagnosis in terms of sociodemographic

characteristics and questions from the questionnaire on mental

disorders, the χ² test was applied.In addition to the statistical

significance, the differences in the prevalence of individual

psychological symptoms among the examined groups in this study were

compared semiquantitatively according to the following scale:

frequency up to 10% was considered insignificant, 11% to 20% was

considered moderate, and 21% to 40% % of frequency of psychological

symptoms was considered high, while frequency of over 41% was

determined to be extremely high.

Results

A total of 200 subjects participated in the study, half of whom

had a mental disorder, while the other half of the subjects had no

mental disorders.

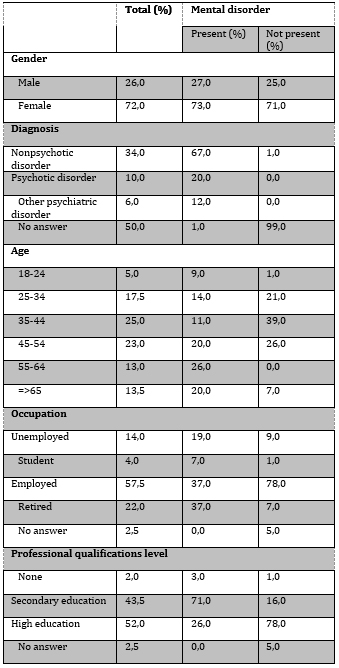

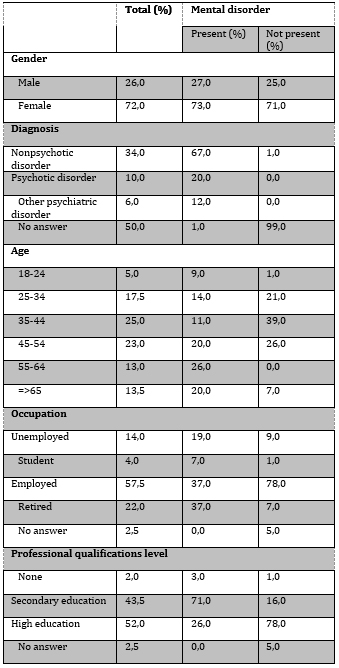

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics on the

whole sample (N = 200) and according to the presence of a mental

disorder

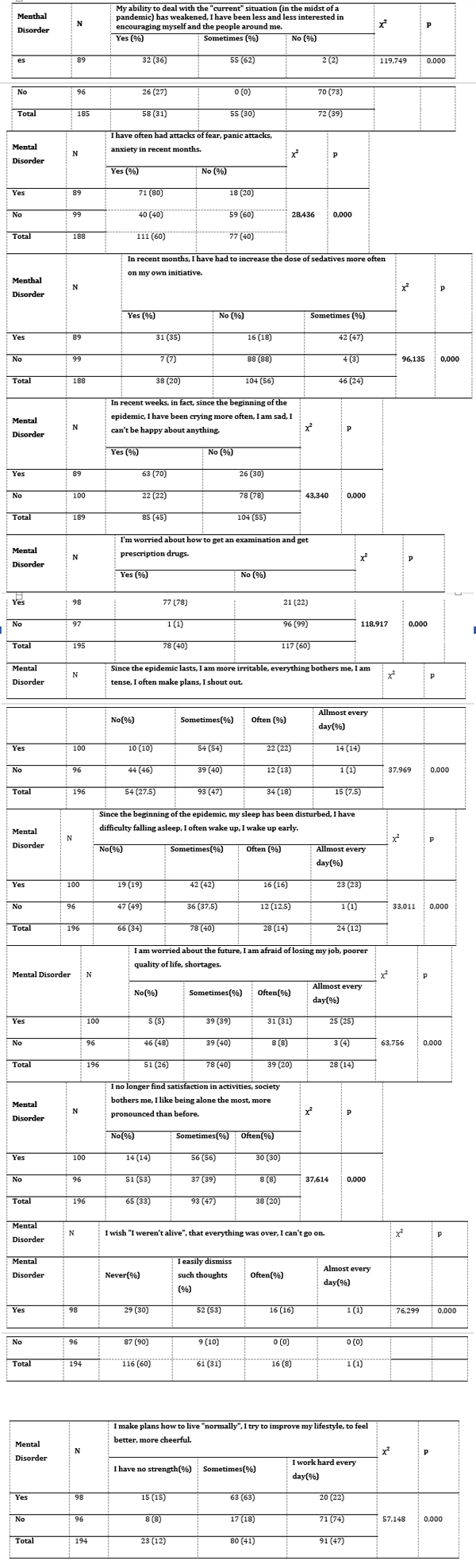

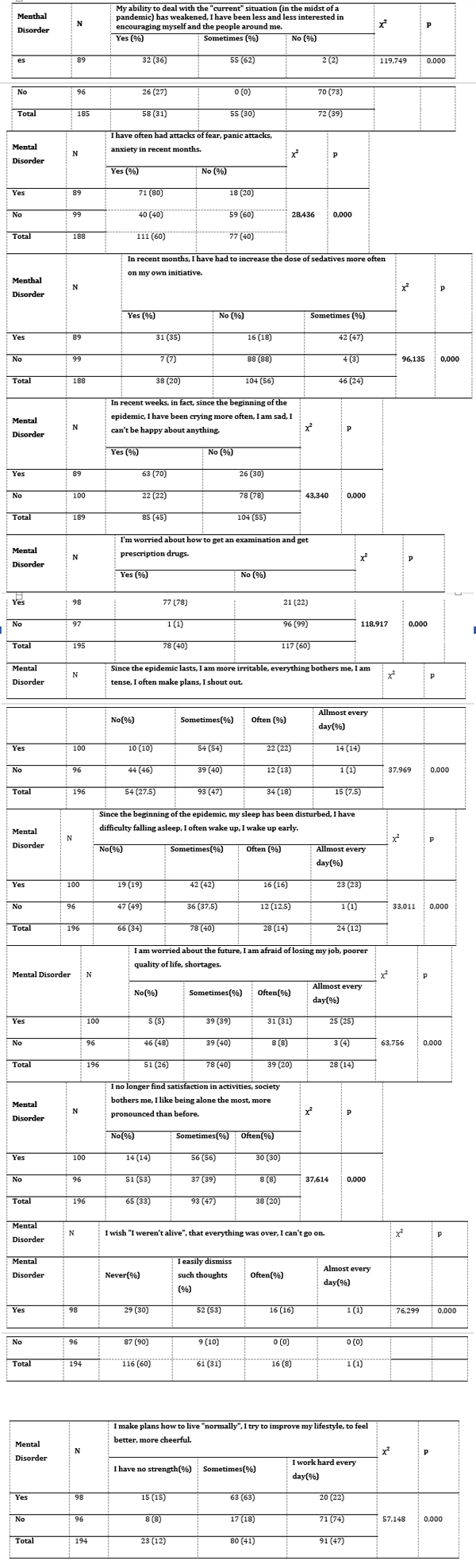

Table 2. Comparison of two groups of respondents

(with and without mental disorders) regarding the questions from the

questionnaire on mental state

Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare the state of mental health

in psychiatric patients with previously mentally healthy people

during and after the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic in

Serbia. The results of this study suggest that all the observed

symptoms are far more frequent and more pronounced in the population

of patients previously suffering from psychiatric diseases compared

to healthy subjects. Anxiety-depressive symptoms dominate in the

form of more frequent panic attacks, feelings of inability to cope

with the current crisis situation, irritability, tension and

constant worries about the future regarding their own health and

uncertain financial situation and future quality of life, and

feelings of loss of satisfaction and depressed mood. Then there is

the concern about the lack of adequate health care during curfews

and lockdowns, and self-initiated use / abuse of

psychopharmaceuticals. Also, problems with sleep and sleep in the

form of insomnia, difficulty falling asleep, intermittent and easy

sleep are much more common in the group of mentally ill people.

Also, the presence of suicidal thoughts is also more common in

subjects with mental disorders. Among the respondents from general

population without pre-existing mental disorder, ie. among the

respondents from the control group there was a statistically

significantly lower presence of symptoms and signs related to mental

problems, although in this group the percentage of symptoms of

mental disorders is not negligible (anxiety, fear, panic attacks

(40%), depressive symptoms. However, this group of respondents (92%)

is of the opinion that it is necessary to fight to overcome the

current crisis, to do their best to “live normally, feel happier and

better. Despite all the hardships and troubles, these results show a

significantly higher incidence of anxiety and depressive symptoms

among the general population in Serbia compared to most similar

studies around the world related to the first outbreak of the

SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic Namely, the percentage of anxiety and

depression among general population during the first attack of the

SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic is 26% and 17% in China, 21% and 18% in

Italy, 22% and 19% in Spain, and Saudi Arabia and 24% and 29%

(8-11). This discrepancy in the results between our and world

studies is a consequence of cultural differences, but also of the

efficiency of the public health authorities of our country in

suppressing the first wave of the epidemic, but also in the

strictest measures to suppress the epidemic, such as state of

emergency and total social restriction.

In the initial wave of the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic in Serbia,

there were no more than 400 infected per day and the mortality rate

was up to 1%. With timely public health intervention, the epidemic

was effectively and relatively quickly contained (12).However, the

strictest epidemiological measures, such as the absolute ban on

movement during the state of emergency in our country, have left a

significant mark on the mental health of the general population,

which is reflected in significantly higher rates of tension, anxiety

and fear among our general population which are almost twice as high

than in European countries such as Italy and Spain, and the

countries of the Middle and Far East such as Saudi Arabia and China.

The rate of depression among the general population is within the

world average.

On the other hand, paradoxically, all these factors have contributed

to the majority of the healthy population mobilizing their defense

mechanisms, to awaken empathy, care for the general safety and

health of vulnerable groups of people. Morality and fighting spirit

were at the highest level, and therefore the psychopathological

phenomena examined were not significantly examined, but the values

obtained are by no means negligible, especially in terms of the

frequency of anxiety.Most people have found additional sources of

psychic energy and strength to cope with a stressful situation and

not succumb to psychopathological manifestations in the first place

(13). Taking the above into account, it can be expected that the

most pronounced effects of a pandemic on mental health in the

general population will be visible only after the situation has

calmed down, when the overstretched healthy defense mechanisms in

humans subside, for which high prevalence of fear, anxiety and

tension among the general population are a sure pre-sign. Patients

with mental illness certainly represent a vulnerable social group

that is particularly sensitive to each new crisis and stressful

situation, which further worsens their already fragile mental

health.This was once again confirmed by the results of our study.

Certainly, the capacities for healthy overcoming of crisis

situations due to mental illness in patients with psychiatric

disorders have been reduced. The results of our study support such

attitudes. For psychiatric patients, social interactions of crucial

importance for their rehabilitation are of particular importance.

And as quarantine and physical distancing measures are in place in a

pandemic, psychiatric patients are prevented from continuing with

daily group rehabilitation treatments and therapeutic group

activities. Such circumstances often leave psychiatric patients

alone with enough time to ruminate their psychopathological

contents, which inevitably manifests itself through anxiety and

tension, and a depressed mood with all its other correlates (14). In

addition to the general feeling of fear and uncertainty, among

psychiatric patients, there is a particular concern about the

availability of medical care in terms of prescribing drugs that

patients use regularly. Namely, over three quarters of the

participants in the study with a mental disorder stated that they

were concerned about the availability of doctors and medical care,

especially in terms of prescribing prescriptions for

psychopharmaceuticals. In our study, respondents (statistically

significantly increased number of former psychiatric patients)

stated that due to growing anxiety and worry, they need to increase

the dose of tranquilizers on their own initiative. From these facts,

a clear conclusion follows that most psychopharmaceuticals were

procured illegally, without a doctor's prescription, which is still

possible in our country. Although it is also clear that the word is

primarily about benzodiazepines, as the most common sedatives and

sleeping pills. A study by Chinese authors, on the other hand, notes

that a significant number of psychiatric patients stopped using

psychopharmaceuticals during the epidemic, because it was not

possible to obtain them through a doctor's prescription (15). As

around the world, there are several reasons in Serbia for mental

health care to be relegated to the background. In the first place,

of course, is the care for the physical health due to the SARS-CoV-2

viral pandemic and the protection of the population from infectious

diseases. Also, health systems have largely reoriented themselves to

providing assistance to patients with Covid 19. All other patients,

including psychiatric ones, have been advised not to see the doctor

unnecessarily, in order to reduce the pressure on the health system.

On the other hand, the patients themselves avoided visiting the

doctor for fear of becoming infected (16). Emergency psychiatric

care was also provided to a much lesser extent both in Serbia and

around the world, as evidenced by the results of a study by Italian

authors (17). Regarding suicide in the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2

viral pandemic , according to the results of our study in the total

sample, about a third of the respondents had suicidal thoughts.

There is a statistically significant difference in the two examined

groups in relation to the occurrence of sicidal thoughts. Far more

respondents of psychiatric patients (approximately 66%) in the

conditions of the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic, stated that on a number

of occasions they thought of taking their own lives. For the sake of

comparison, in the control group of mentally healthy people, the

rate of suicidal thoughts is about 9%. Certainly, the frequency of

suicidal ideation correlates positively with the increase in the

intensity of mental symptoms in the group of psychiatric patients

compared to mentally healthy controls. There is little data on

suicide rates at the time of the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic . The

data available to us are from a study by authors from Bangladesh

where it is stated that the incidence rate of suicidal thoughts and

thinking in the general population is about 6% at the beginning of

the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic (18). In this study, as well in as

several others, loneliness, social isolation, depressed mood, and

fear are highlighted as leading risk factors for suicidal ideation

and attempts. The most susceptible to such phenomena are medical

workers who participate in the treatment of infected patients, but

also the infected patients themselves (19,20). In European

countries, there has been a significant decline in the number of

suicides during the first "lockdown" period, according to prominent

news agencies, although these data still need to be scientifically

substantiated (20).There are no clear data in the world regarding

the occurrence of suicide in psychiatric patients at the time of the

SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic. Most authors who touch on this topic only

state that the presence of a mental disorder and the SARS-CoV-2

viral pandemic represent "double-susceptibility" to suicide (21).

Suicide rates are expected to decrease during the stressful

situation of a large number of people as they focus on maintaining

both their own health and the health of others (22). Only after the

action of the stress factor, after the defense mechanisms have

subsided, does a person turn to thinking about himself and his own

re-examination, which is a suitable ground for the appearance of

suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

Conclusion. We found that the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic after its

first outbreak in Serbia left double consequences on the mental

health of the healthy population and those previously suffering from

psychiatric illnesses. Namely, psychiatric patients responded to the

first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic and all the restrictive

measures that followed it with a significant worsening of

psychopathological symptoms. Anxiety and depressive symptoms, as

well as sleep disorders, but also the presence of suicidal thoughts

and thoughts are mostly recorded. While, on the other hand, mentally

healthy participants in the control group had a statistically

significantly lower presence of symptoms and signs associated with

mental problems, although in this group the percentage of symptoms

of mental disorders is not negligible, which supports the thesis

that mental retardation The CoV-2 virus brought with it, especially

in the long run, leads to serious mental disorders, which is

predicted by world experts in the field of mental health (7).These

results clearly show once again that psychiatric patients represent

a vulnerable social group, whose mental health should not be

neglected under any circumstances, and especially in stressful

situations such as the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic . Our findings can

be used to plan public health interventions in the field of mental

health targeting both general and vulnerable populations combined

with efforts to respond to certain future pandemics in their early

stages, with the aim of to obtain a comprehensive response in which

even mental health will not be neglected. Limitations of the study

This study may be limited by its design (cross-sectional study), as

well as the method of data collection (independent and online

completion of self-assessment questionnaires), also by the fact that

standardized psychiatric-psychological questionnaires were not used

to assess mental health. It is possible to assess the intensity of

psychopathological symptoms. These limitations may methodologically

weaken the study. However, despite the possible limitations of the

study, it provides new and interesting data on different

psychological responses to the SARS-CoV-2 viral pandemic in two

groups of people who are different by the presence/absence of a

mental disorder, and is therefore unique in the area, wherethere is

a lack of information on global level.

LITERATURE:

- Maunder R, Hunter J, Vicent L, Bennett J, Peladeau N, Leszcz

M, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of

the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ

2003;168:1245–51.

- Mak IWC, Chu CM, Pan PC, Yiu MGC, Chan VL. Long-term

psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. Gen. Hosp.

Psychiatry. 2009;31, 318–26.

- Van der Weerd W, Timmermans DR, Beaujean DJ, Oudhoff J, van

Steenbergen

JE. Monitoring the level of government trust, risk perception

and intention of the

general public to adopt protective measures during the influenza

A (H1N1) pandemic

in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:575. doi:

10.1186/1471-2458-11-575.

- Dar KA, Iqbal N, Mushtaq A. Intolerance of uncertainty,

depression, and anxiety: examining the indirect and moderating

effects of worry. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2017;29, 129–33.

- Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L, et al.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general

population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord.

2020;1(277):55-64.

- Pietrabissa G, Simpson SG. Psychological Consequences of

Social Isolation During COVID-19 Outbreak. Front. Psychol. 2020;

11:2201.

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S,

Greenberg N. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to

reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet Psychiatry.

2020; 395(10227): 912–20.

- González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Ángel Castellanos M, Saiz J,

López-Gómez A, et al. "Mental health consequences during the

initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in

Spain." Brain Behavior and Immunity 2020;87:172-176. doi:

10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040.

- Zhou J, Liu L, Xue P, Yang X, Tang T. "Mental health

response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China." Am J Psychiatry.

2020; 177(7): 574-575. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304.

- Alkhamees AA, Alrashed SA, Alzunaydi AA, Almohimeed AS,

Aljohani MS. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on

the general population of Saudi Arabia. Comprehensive

Psychiatry. 2020;102:152192.

- Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, Mensi S, Niolu C. et al.

COVID-19 Pandemic and Lockdown Measures Impact on Mental Health

Among the General Population in Italy. Frontiers in Psychiatry,

2020;11:790. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790.

- Objave centra za javno zdravlje – COVID-19. Available from:

https://covid19.rs/objave-centra-za-javno-zdravlje/ [cited 2

December 2020].

- Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic | NEJM [Internet].

New England Journal of Medicine. Available from:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [cited 2

December 2020].

- Neelam K, Duddu V, Anyim N, Neelam J, Lewis S. Pandemics and

pre-existing mental illness: A systematic review and

meta-analysis Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666354620301423

[cited 2020 Dec10].

- Zhou J, Liu L, Xue P, Yang X, Tang X. Mental health response

to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Psychiatry

2020;177(7):574-575. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304.

- Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, Zhang L, Zhao X. et al. Do

psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during

COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with

service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain

behavior and immunity. 2020;87:100-106. doi:

10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069.

- Capuzzi E, Di Brita C, Caldiroli A, et al. Psychiatric

emergency care during Coronavirus 2019 (COVID 19) pandemic

lockdown: results from a Department of Mental Health and

Addiction of northern Italy. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113463.

- Mamun MA, Akter T, Zohra F, Sakib N, Bhuiyan AKMI, Banik PC,

et al. Prevalence and risk factors of COVID-19 suicidal behavior

in Bangladeshi population: are healthcare professionals at

greater risk? 2020;6(10):e05259. Available from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844020321022

[cited 2020Dec10].

- Reger M.A., Stanley I.H., Joiner T.E. Suicide mortality and

coronavirus disease 2019—a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry. 2020.

- Banerjee D., Vaishnav M., Rao T.S., Raju M.S.V.K., Dalal

P.K., Javed A., Saha G., Mishra K.K., Kumar V., Jagiwala M.P.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychosocial health and

well-being in South-Asian (World Psychiatric Association zone

16) countries: A systematic and advocacy review from the Indian

Psychiatric Society. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2020;62(9):343.

- Banerjee D, Kosagisharaf JR, Sathyanarayana Rao TS. 'The

dual pandemic' of suicide and COVID-19: A biopsychosocial

narrative of risks and prevention. Psychiatry Res.

2021;295:113577. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113577.

- Yao H., Chen J.H., Xu Y.F. Patients with mental health

disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry.

2020;7(4):e21.

|

|

|

|