| |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol consumption is increasingly a socially acceptable

activity, favored to the level of a mandatory ritual in many social

situations [1]. Globally, approximately 90% of people consume

alcohol at some point in their lives, while 3-5% is women and 10%

are addicted to alcohol[1]. Alcohol is a risk factor for 60

different medical conditions, and more than 4% of diseases are

directly related to alcohol consumption [2]. The economic burden of

alcohol consumption is estimated at more than 1% of the gross

national product in middle-developed and highly developed countries

[3]. Tolerance of the environment to alcohol consumption is high, so

from the intake of small doses of alcohol to clinical and physical

signs of intoxication, a lot of valuable time passes[4]. Society

enters the scene too late, usually with its system of condemnation

and isolation4. As a result, alcohol abuse causes approximately 3

million deaths each year (5.3% of deaths) [3].

Spirituality encompasses the existential need of each individual to

find answers and discover the purpose of life as well as the need to

believe in something greater than ourselves that connects all people

with each other [5,6]. Existential well-being implies a sense of the

meaning and purpose of existence, competence and the ability to

accept limitations [7]. Low levels of perceived meaning of one's own

life predispose to excessive alcohol consumption [8]. The content

and clarity of religious norms on alcohol use and the religiosity of

the individual determine the influence of religion on alcohol

consumption [9]. Christianity has prescribed norms on the use of

wine (not alcohol) in worship, but does not restrict moderate

consumption of alcohol (strong drinks), for refreshment or health

reasons [10]. The religiosity of the individual is a significant

modifier of the structure of values, as well as an important

predictor of a wide range of attitudes and behaviors, including

alcohol consumption4.

The aim of the research was to determine the frequency of alcohol

consumption and to assess the connection between the determined

consumption and the religiosity and existential well-being of the

adult population of the Orthodox religion in Krupa na Uni.

METHODS

The test as a cross-sectional study was conducted in a period of

three months, from 01.08.2021. to 11.01.2021. The respondents were

registered in the family medicine team of the Primary Health care

Center of the Krupa Health Center in Uni. During the regular work in

the family medicine Center, 103 adults aged 20 to 65 were selected

by random sampling. The study did not include people diagnosed with

alcoholism spectrum disorder or syndrome involved in treatment,

rehabilitation and resocialization, people with mental illness or

disorder, malignant and advanced chronic diseases. Data were

collected on the basis of anamnesis, available medical documentation

and filling out specific questionnaires.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was developed

and recommended by the World Health Organization for the early

identification of risky and harmful drinking as well as alcohol

dependence [11,12]. It consists of three questions in the field of

risky alcohol use (frequency of drinking, typical amount, frequency

of heavy drinking), four questions in the field of harmful alcohol

use (guilt after drinking, amnesia, injuries due to alcohol

consumption, environmental concerns) and three questions (decreased

control over drinking, increased desire to drink, morning drinking)

which are scored 0-4 [11,12]. The measuring range ranges from 0 (not

drinking) to 40 (alcohol abuse). A total score of 0 indicates

non-consumption of alcohol, 1-7 on low-risk drinking, 8-15 on risky

drinking and 20-40 on alcohol abuse [11,12]. The questionnaire has

acceptable internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha coefficient 0.86)

[13].

The Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) assesses two dimensions of

spiritual well-being, religiosity and existential well-being

[14,15]. The Religious Well-Being subscale (RWB) evaluates the

relationship with God, while the Existential Welfare subscale (EWB)

analyses the sense of meaning and purpose of existence, competence

and ability to accept limitations [14,15. The subscales contain ten

questions with answers on the Likert scale of 6 points ranging from

"strongly agree" (1) to "strongly disagree" (6) [14,15]. Eight

questions were written in the reverse direction and the reverse was

scored [14,15]. The measuring range of the questionnaire ranges from

20 to 120, the measuring range of the subscale from 10 to 60

[14,15]. The overall questionnaire score of 20 to 40 indicates low,

41 to 99 moderate, and 100 to 120 high spiritual well-being [14,15].

The total result of the subscale from 10 to 20 is interpreted as

low, from 21 to 49 as moderate and from 50 to 60 as high religiosity

or existential well-being [14,15]. The subscales have acceptable

internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients 0.91 and 0.84)

[14,15]. For specific purposes, e.g. focusing only on religiosity

and / or only on existential well-being, the authors allow

individual use of subscales [14].

Contingency tables based on the nonparametric Chi square test were

used to determine statistical significance. The significance level

is set to 95% confidence interval. The results are presented

textually and tabular, the complete work is processed in the text of

the Microsoft Word processor for Windows. P values that could not be

expressed to a maximum of three decimal places are shown as p <0.001

[16].

RESULTS

The study included 103 adults aged 20 to 65 years. Among them were

57 (55.3%) men and 46 (44.7%) women. The mean age of the examined

population was 44.7 ± 10.45 years.

Alcohol was not consumed by 21 (20.4%) participants in the study,

while 82 (79.6%) consumed it with different frequency (low-risk

drinking 53.4%, risky drinking 16.5%, harmful drinking 2.9% and

alcohol abuse 6.8%).

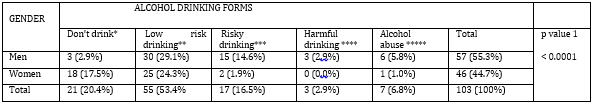

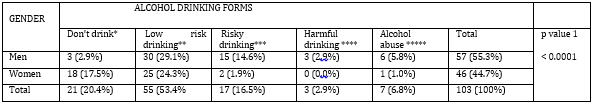

Risky drinking was found in 15 (14.6%) men, harmful drinking in 3

(2.9%) and alcohol abuse in 6 of them (5.8%). Harmful drinking was

not found in women, 2 (1.9%) women drank at risk and 1 (1%) abused

alcohol. Males were significantly more likely to consume alcohol (p

<0.0001). Table 1.

Table 1: . Interrelations between a participants' gender and alcohol

drinking forms according to the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification

Test score

*AUDIT score 0; **AUDIT score 1-7; ***AUDIT score 8-15; ****

AUDIT score 16-19; ***** AUDIT score 20-40; 1p according to Chi

Quadrat Test.

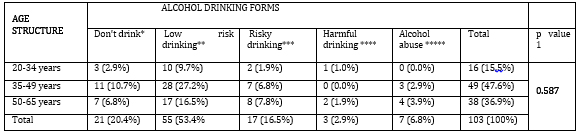

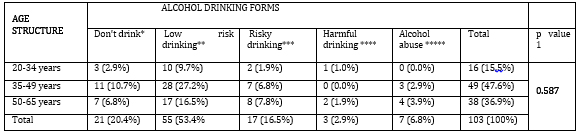

Out of a total of 16 (15.5%) respondents aged 20 to 34, none abused

alcohol, while only 1 (1%) consumed alcohol within the limits of

harmful drinking. Out of a total of 49 (47.6%) respondents aged 35

to 49, none consumed alcohol within the limits of harmful drinking,

while 3 (2.9%) abused alcohol. Of the remaining 38 (36.9%)

respondents aged 50 to 65, 2 (1.9%) consumed alcohol within the

limits of harmful drinking, while 4 (3.9%) abused alcohol. Age did

not have a significant effect on alcohol consumption (p = 0.587).

Table 2.

Table 2. Interrelations between a participants' age structure and

alcohol drinking forms according to the Alcohol Use Disorders

Identification Test score

*AUDIT score 0; **AUDIT score 1-7; ***AUDIT score 8-15; ****

AUDIT score 16-19; ***** AUDIT score 20-40; 1p according to Chi

Quadrat Test.

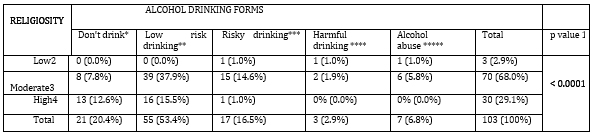

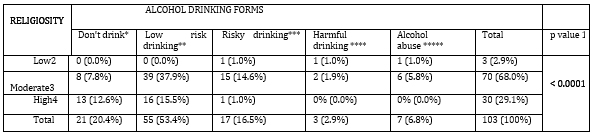

Low religiosity was found in 3 (2.9%) respondents, moderate in 70

(68.0%), while 30 (29.1%) were highly religious. The average value

of the subscale of religiosity of the respondents was 41.75

(moderate religiosity) with an average deviation of 10.23. In the

group of low-religious respondents, there were no respondents who do

not drink and consume alcohol within the limits of low-risk

drinking. On the other hand, in the group of highly religious

respondents, there were no respondents who drink or abuse alcohol. A

significant correlation/influence of religiosity on alcohol

consumption was found among the respondents (p <0.0001). Table 3.

Table 3: Interrelations between a participants' religiosity

according to po Religious Well-Being score and alcohol drinking

forms according to the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

score

*AUDIT score 0; **AUDIT score 1-7; ***AUDIT score 8-15; **** AUDIT

score 16-19; ***** AUDIT score 20-40; 1p according to Chi Quadrat

Test. ; RBW score 10-20; 3RBW score 21-49; 4RBW score 50-60.

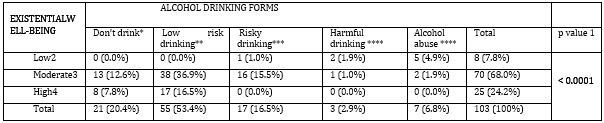

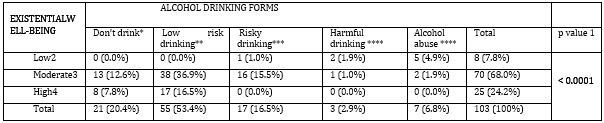

Low existential well-being was found in 8 (7.8%) respondents,

moderate in 70 (68.0%) and high existential well-being in 25

(24.2%). The average value of the subscale of existential well-being

of the respondents was 40.36 (moderate existential well-being) with

an average deviation of 10.93. In the group of respondents with low

existential well-being, the largest number of respondents abuse

alcohol, 5 (4.9%). There were no respondents who do not drink and

consume alcohol within the limits of low-risk drinking. On the other

hand, in the groups with high existential well-being, there were no

respondents who consume alcohol within the limits of risky drinking,

drink harmful or abuse alcohol. A significant correlation/impact of

existential well-being on alcohol consumption was found in the

subjects (p <0.0001). Table 4.

Table 4: Interrelations between a participants' existential

well-being according to po Existential Well- Being score and alcohol

drinking forms according to the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification

Test score

*AUDIT score 0; **AUDIT score 1-7; ***AUDIT score 8-15; ****

AUDIT score 16-19; ***** AUDIT score 20-40; 1p according to Chi

Quadrat Test. ; EBW score 10-20; 3EBW score 21-49; 4EBW score 50-60.

DISCUSSION

Excessive alcohol consumption impairs the physical and mental health

of the consumer and adversely affects the health and well-being of

persons in his environment17. Worldwide, 32.5% of people consume

alcohol (25% of women and 39% of men) [17]. The average amount of

alcohol consumed is 0.73 standard drinks per day for women and 1.7

standard drinks per day for men17. A small but significant part

(3.5% in developed countries) of the adult population has developed

alcohol dependence, while risky and harmful drinking has been

identified in a significantly higher percentage (15-40%) [18].

The average daily intake of pure alcohol in Bosnia and Herzegovina

is 29 g (13.4 l of pure alcohol, of which 75.8% beer, 8.6% wine,

12.4% spirits and 3.2% other alcoholic beverages) [19]. Alcohol

intoxications were recorded in 22.7% of the population (36.4% of men

and 8.6% of women) [19]. Harmful drinking was found in 2.5% of the

population, alcohol dependence at 3.4%. Approximately 19.6.0% of the

population has health problems due to alcohol use [19]. Alcohol use

is the cause of death in 4.6% of the population of Bosnia and

Herzegovina (7.7% of men and 1.5% of women) [19].

In our study, 79.6% of respondents consumed alcohol (53.4% low-risk

drinking, 16.5% risky drinking, 2.9% harmful drinking and 6.8%

alcohol abuse). Males were more likely to consume alcohol. The age

of the respondents did not have a significant impact on alcohol

consumption.

Religiosity encompasses five fundamental dimensions inherent in all

religions: ideological (expectation that a religious person will

accept certain beliefs), experiential (expectation that a religious

person will experience religious feelings), ritual (encompasses

specific religious practices required of a religious person),

intellectual (expectation that the religious person will be

acquainted with the basic principles of his faith), consequential

(includes the secular effects of religious belief, practice and

experience on the religious person) [4,20].

Religiosity is a significant modifier of the structure of values, as

well as an important predictor of a wide range of behaviors and

attitudes [21,22]. It allows moral values to receive a supernatural

sanction that empowers them in their obligation and coercion

[21,22]. It contributes to the respect of authority and institutions

in general, because God, especially monotheistic, is a symbol of

social authority [21,22]. It has a positive effect on self-control

and resistance to negative influences [21,22]. It can answer the

question of the meaning and value of life which can consequently

reduce the attractiveness of alcohol consumption [21,22].

The protective influence of religiosity on alcohol consumption is

also determined by the specificity of religion [10]. It is assumed

that members of religious groups that are characterized by strict

and clear prohibitions on alcohol consumption will resort to it to a

lesser extent [10].

Islam completely forbids the production, sale, donation and keeping

of alcohol in the homes of believers [10]. On the other hand,

Christianity does not have completely clear guidelines or

restrictions regarding the quantity or purpose of the use of alcohol

outside religious ceremonies (consumption of alcohol for refreshment

or health reasons is allowed) [11].

All participants in the research were of the Orthodox faith.

Moderate religiosity was found in 68% of respondents, high in 29%

and low in 3%. The religiosity of the respondents had a significant

impact on alcohol consumption (p <0.001).

A 38-year prospective cohort study involving 1,795 children of

Hindu, Islamic and Christian faiths from the island of Mauritius

found that religious affiliation reduces the likelihood of drinking

by adults who believe their religion promotes abstinence [10]. A

survey of 526 third- and fourth-year students at eight faculties of

the University of Tuzla found a strong association between all 5

domains of religious status and patterns of alcohol consumption4. A

survey of 495 adults (Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, and

nonreligious adults) in the United States found that nonreligious

adults and Buddhists had significant positive attitudes toward

alcohol use toward Christians and Muslims [23]. A study in Scotland

involving 4,066 students found that non-religious students consumed

significantly more alcohol (women more than 14 standard drinks per

week, men more than 21 standard drinks per week) [24]. A study in

Yemen among 146 adults in two centers for the treatment of alcohol

and other psychoactive substance addiction found that religiosity

plays an important role in the process of recovery and prevention of

re-abuse [25]. A survey in Brazil among 3,007 adults in 143 cities

identified a strong association between religiosity and negative

attitudes toward alcohol, including limited sales time, reduced

store availability, ban on advertising, tax increases, and minimum

legal benefits for alcohol consumption [26].

Existential well-being is determined by the essential issues of

human existence and the ability to engage in the process of creating

meaning [27]. Meaning does not come from human existence itself, it

is something that an adult faces and discovers[28]. Taking

existential responsibility for one's life (accepting or rejecting

the offered meaning) each individual comes to the consciousness of

the same self [28].

The absence of meaningfulness (existential vacuum) reduces the

perception of the meaning of one's own life and predisposes to

potentially risky behaviors29. In addition, it causes apathy,

emptiness, low self-esteem and frustration [28,29].

By consuming alcohol, an existentially frustrated adult creates the

illusion of meaning, belonging and self-esteem [27].

68% of respondents had moderate existential well-being, 24.2% high

and 7.8% low. The existential well-being of the respondents had a

strong influence on alcohol consumption (p <0.001)

A study of 151 students aged 18 to 25 in the United States

identified an inverse association of existential well-being with

patterns of alcohol consumption and the likelihood of attending a

social event that included alcohol [30]. In addition, existential

well-being is an important predictor of alcohol prevention [30]. A

study of 176 adults aged 18 to 30 in Australia found significantly

higher alcohol consumption in the presence of an existential vacuum

[29]. A study in Canada, which included 131 adults hospitalized in a

psychiatric clinic, found that an addiction treatment program

contributes to the growth of meaningful life [31].

CONCLUSION

Almost 80% of the participants in the research consumed alcohol, of

which two-thirds were part of low-risk drinking. Males were

significantly more likely to consume alcohol. The age of the

respondents did not have a significant impact on alcohol

consumption.

All respondents are of the Orthodox faith. Most are moderately

religious. There is a significant correlation/influence of

religiosity in alcohol consumption among respondents.

Most study participants have a moderate degree of existential

well-being. Participants with a high degree of existential

well-being consume significantly less alcohol, compared to

respondents who have moderate or low existential well-being.

LITERATURE:

- Sher L. Depression and alcoholism. QJM: An International

Journal of Medicine. 2004; 97(4):237–240. Available from:

https://academic.oup.com/qjmed/article/97/4/237/1525431

- Žuškin E, Jukić V , Lipozenčić J, Matošić A, Mustajbegović

J, Turčić N et al. Alcohol and workplace. Arh Hig Rada Toksikol.

2006;57:413-426. Available from:

https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/9214.

- Glantz MD, Bharat C, Degenhardt L, Sampson NA, Scott KM, Lim

CCW et al. WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators. The

epidemiology of alcohol use disorders cross-nationally: Findings

from the World Mental Health Surveys. Addict Behav.

2020;102:106128. Available from:

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2020-24294-001

- Jašić O, Hodžić Dž, Selmanović S. Utjecaj religijskog

statusa i kvalitete života na konzumaciju alkohola među

studentskom populacijom Sveučilišta u Tuzli. JAHR. 2012;3(5).

Available from: https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/130059.

- Leutar Z, Leutar I. Religioznost i Duhovnost u socijalnom

radu. Crkva u svijetu. 2010;45(1):78-103. Available from:

https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/76620

- Dučkić A, Blažeka Kokorić S. Duhovnost – resurs za

prevladavanje kriznih životnih situacija kod pripadnika

karizmatskih zajednica. Ljetopis socijalnog rada.

2014;21(3).425-452. Available from:

https://www.academia.edu/49511095/Duhovnost_Resurs_Za_Prevladavanje_Kriznih_%C5%BDivotnih_Situacija_Kod_Pripadnika_Karizmatskih_Zajednica

- Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets AJJM. Existential

Well-Being Spirituality or Well-Being? The Journal of Nervous

and Mental Disease. 2017;205(3),234-241. Available from:

https://journals.lww.com/jonmd/Abstract/2017/03000/Existential_Well_Being_

Spirituality_or.13.aspx

- Vondras DD, Schmitt RR, Marx. Associations between aspects

of spiritual well-being, alcohol use, and related

social-cognitions in female college students. Journal of

Religion and Health. 2007;46(4):500-515- Available from:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/27513039

- Luczak SE, Prescott CA, Dalais C, Raine A, Venables PH,

Mednick SA. Religious factors associated with alcohol

involvement: results from the Mauritian Joint Child Health

Project. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;135:37-44. Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259317859_Religious_Factors_Associated_

with_Alcohol_Involvement_Results_from_the_Mauritian_Joint_Child_Health_Project

- Golik-Gruber V. Alkohol u očima vjerskih zajednica. U:

Zbornik stručnih radova Alkohološkog glasnika. Zagreb

2003;74-76. Available from:

http://www.moravek.org/kla/61-003.html.

- Toković S, Bivolarević S, Đurišić Lj, Arsić A, Čeković J,

Srećkov M et al. Alkoholizam i psihijatrijski komorbiditet u

primarnoj zdravstvenoj zaštiti. Sanamed. 2010;5:35-38. Available

from:

http://www.sanamed.rs/sanamed_pdf/sanamed_5/Snjezana_Tokovic.pdf

- Skandul D, Ožvačić Adžić Z, Hanževački M, Šimić D. Procjena

poremećaja uzrokovanih alkoholom u radu obiteljskog liječnika-pilot

istraživanje. Procjena poremećaja uzrokovanih alkoholom u radu

obiteljskog liječnika – pilot istraživanje Med Fam Croat.

2017;25(1-2):17-16. Available from:

https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/277174

- Rubio Valladolid G, Bermejo Vicedo J, Caballero Sánchez-Serrano

MC, Santo-Domingo Carrasco J. Validación de la prueba para la

identificación de trastornos por uso de alcohol (AUDIT) en

Atención Primaria [Validation of the Alcohol Use Disorders

Identification Test (AUDIT) in primary care]. Rev Clin Esp.

1998;198(1):11-4. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7676097

- Malinakova K, Kopcakova J, Kolarcik P, Geckova AM, Solcova

IP, Husek V et al. The Spiritual Well-Being Scale: Psychometric

Evaluation of the Shortened Version in Czech Adolescents. J

Relig Health. 2017;56(2):697-705. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5320003/

- Nakane S. The Influence of Faith and Religiosity in Coping

with Breast Cancer. ARC Journal of Psychiatry. 2017; 2(4): 1-8.

Available from:

https://www.arcjournals.org/journal-of-psychiatry/volume-2-issue-4/1.

- Petrovečki M. Statistički temelji znanstvenoistraživačkog

rada, u: Matko Marušić (ur.), Uvod u znanstveni rad u medicini.

Medicinska Naklada. Zagreb. 2000.

- Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C, Arian N, Zimsen SRM,

Tymeson HD et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and

territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global

Burden of Disease Study. 2016. Lancet 2018; 392:1015–35.

Available from:

https://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140-6736(18)31310-2/fulltext

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC. Brief Intervention For

Hazardous and Harmful Drinking. A Manual for Use in Primary

Care. 2001. Available from:

https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/14105/1/WHO_Brief_intervention.pdf.

- Geneva: World Healh Organization. Global status report on

alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization.

2018. Available from:

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639.

- Jusić M. Psihološka dimenzija religije i religijske

motivacije. Novi muallim. 2006;25(29):60-65. Available from:

https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=568406.

- Flere S. Religioznost i delikventnost: istraživačke

rezultati na populaciji mariborskih studenata. Druš. Istraž.

Zagreb 2005;3(77):531-544. Available from:

https://hrcak.srce.hr/17856.

- Rohrbaugh J, Jessor R. Religiosity in youth: A personal

control against deviant behavior. Journal of personality. 1975;

43(1):136-155. Available from:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1975.tb00577.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed

- Najjar LZ, Leasure L, Henderson CE, Young CM, Neighbors C.

Religious perceptions of alcohol consumption and drinking

behaviours among religious and non-religious individuals. Mental

Health Religion & Culture. 2017;19(9):1-14. Available from:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13674676.2017.1312321?journalCode=cmhr20

- Engs RC, Mullen K. The Effect of Religion and Religiosity on

Drug Use Among a Selected Sample of Post-Secondary Students in

Scotland. Addiction Research. 1999;7(2):149-170. Available from:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/16066359909004380

- Al-Omari H, Hamed R, Abu Tariah H. The Role of Religion in

the Recovery from Alcohol and Substance Abuse Among Jordanian

Adults. J Relig Health. 2015;54(4):1268-77. Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262024828_The_Role_of_Religion_in_the_Recovery_

from_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_Among_Jordanian_Adults

- Lucchetti G, Koenig HG, Pinsky I, Laranjeira R, Vallada H.

Religious beliefs and alcohol control policies: a Brazilian

nationwide study. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2014;36(1). Available

from:

https://www.scielo.br/j/rbp/a/qQvmCC4HpwhQFvGpKLZvPjR/?lang=en

- Sung L. An Exploration of Existential Group Art Therapy for

Substance Abuse Clients with a History of Trauma. LMU/ LLS

Theses and Dissertations. 2016. Available from:

https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1285&context=etd

- Radinov T. Smisao života i patnje promatran kroz katoličko–teološku

i psihološko–logoterapijsku perspektivu. Obnov život.

2017;72(4):517–529. Available from: https://hrcak.srce.hr/193039

- Csabonyi M, Phillips LJ. Meaning in Life and Substance Use.

Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2020;60(1):3-19. Available

from:

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0022167816687674

- Wood RJ, Hebert EP. The relationship between spiritual

meaning and purpose and drug and alcohol use among college

students. American Journal of Health Studies.

2005;20(1/2):72-79. Available from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235349772_The_relationship_between_

spiritual_meaning_and_purpose_and_drug_and_alcohol_use_among_college_students

- Waisberg JL, Porter JE. Purpose in life and outcome of

treatment for alcohol dependence. Br J Clin Psychol.

1994;33(1):49-63. Available from: https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1994.tb01093.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed

|

|

|

|