| |

|

|

1. Introduction

INTRODUCTION

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) in its 2017

classification includes Self-Limited Epilepsy with Centrotemporal

Spikes among pediatric focal epilepsies [1].

The clinical manifestation typical of Self-limited epilepsy with

centrotemporal spikes (SeLECTS) according to van Hufflen was first

described by Martinus Rulandus in the 17th century (639/1989) [2].

In mid-20th century the first descriptions of epilepsy specific to

children emerged, characterized by certain types of seizures and

identifiable findings in EEG [3]. This type of epilepsy has proven

to have an excellent prognosis, adding a third key characteristic to

the clinical and neurophysiological findings: a benign course.

In attempts to make the name as precise as possible, authors

included three or four terms in the name, each individually

describing the key characteristics of this entity.

In early works addressing this issue, the emphasis was placed on

distinguishing this from other types of epilepsies. This approach

led to the formation of a unique entity that clearly stands apart

from other epilepsies [3].

With the increasing adoption of knowledge, this epilepsy became more

recognizable in clinical practice and better described. Initially,

authors gave various names to this type of epilepsy, namely there

was not a single term used by all authors.

Problems with determining the name of the syndrome

Different names have been used for this type of childhood focal

epilepsy. One group of authors used the eponym "Rolandic," while

others employed a descriptive term, aiming to encapsulate the main

characteristics of this entity and provide a more precise definition

of this type of epilepsy. In their attempts to be more precise,

authors included three or four terms in the name, individually

describing the key features of this entity:

1) The most important characteristic is a benign prognosis, so the

term "Benign" is usually placed first in the name.

2) The determining point related to the time of onset of this

syndrome is child's age. In the names, "children’s or "childhood" is

used.

3) In the third position is the determining point related to focal

occurrence (focal, partial). Some authors omit this determining

point, assuming it is implied when specifying the location of

interictal epileptiform graphoelements in EEG.

4) The next determining point is the location of interictal specific

graphoelements (spike, EEG focus). The location is determined in two

ways: by neurophysiological criteria (centrotemporal, based on

electrodes placed according to the international 10-20 system in

EEG) or by an anatomical model, i.e., the part of the brain where

epileptic discharge is presumed to occur – the Rolandic region,

around the Rolandic fissure. American authors used the term

"mid-temporal" to describe these discharges [4,5], while French

authors preferred "Rolandic spikes" [6,7,8,9].

It has been observed that an identical EEG finding characteristic of

this type of childhood epilepsy also occurs in children without

seizures. In such cases, terms like BFEDCs (Benign Focal

Epileptiform Discharges of Childhood) [10,11,12], or BEDs (Benign

Epileptiform Discharges) [13] are commonly used.

Childhood benign focal epilepsies form a group of epilepsies or

epileptic syndromes sharing common features. According to the ILAE

recommendation [14], these epilepsies are collectively termed

Self-limited focal epilepsies of childhood (SeLFE), previously known

as BCFE - Benign Childhood Focal Epilepsy [12] or Idiopathic focal

epileptic syndromes (IFE) [15].

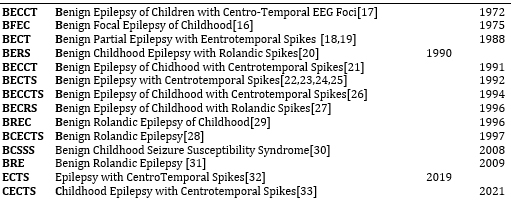

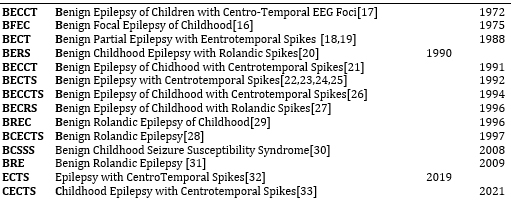

Self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (SeLECTS) is the

most common syndrome in this group, and this term was recommended by

the ILAE in its new nomenclature in 2017 (275-2022). Throughout

history, this type of epilepsy has had various names and

abbreviations. The used names, abbreviations, authors, and

publication years are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. The used names, abbreviations and

publication years for Childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes

The three main characteristics that constitute this entity (SeLECTS)

are: Clinical manifestation, specific EEG findings, and a favorable

prognosis, i.e., a benign course.

Clinical manifestation

The cardinal feature of Rolandic epilepsy is focal epileptic

seizures, which can manifest in various ways typically categorized

into symptom groups [34]:

(1) Unilateral facial sensory-motor symptoms (30% of patients),

(2) Oro-pharyngeal-laryngeal symptoms (53% of patients),

(3) Speech impairment (40%),

(4) Hypersalivation (30%) [30].

In addition to focal seizures, generalized tonic-clonic seizures

also occur, commonly considered secondary generalized.

Beyond the seizure semiology and classification in this syndrome,

anamnesis can provide other relevant data. There is a clear

influence of sleep, drowsiness, and sleep deprivation on the

frequency of seizures. Three-quarters of seizures occur during

non-REM sleep, mainly at the onset of sleep or just before waking up

[30].

Febrile seizures are often encountered in personal history (5-15%)

[1,35].

A positive family history is also frequently found in children with

BECT, indicating a genetic etiology [36].

Specific EEG findings

High-voltage spike-wave complexes activated during drowsiness and

sleep constitute a distinctive finding in this entity (essential for

diagnosis) [1].

The initial part of the graphoelement is commonly described as a

spike, although precise measurements often reveal a sharp wave.

The location is typically specific, and most of the earlier names of

this syndrome were related to this location.

Furthermore, the frequency of spike-wave complexes has been shown to

depend on the wakefulness state, occurring more frequently during

sleep [34].

In repeated EEG recordings, the location of occurrence can change,

so the epileptic focus often appeared in a different place compared

to previous registrations ("spike migration") [37]. This included a

change in the hemisphere, a strong indication that it wasn't a

structural lesion, providing indirect evidence of this entity. The

frequency of spikes in the EEG was not related to the frequency of

seizures, which was a perplexing factor for clinicians. On the other

hand, it was observed that some children with such EEG findings

during nocturnal sleep exhibited almost continuous discharges. This

led to the formation of a new entity (Epilepsy with continuous

spike-and-waves during slow-wave sleep), separating this type of

epilepsy from BECT (216/2001).

Regarding the location, most spikes are found in centro-temporal

regions, but spikes in BECT can also be found outside these regions.

Even though, in some cases, spikes in this entity may appear in

other regions, it is not sufficient reason to exclude it from this

syndrome ([38].

Many researchers have attempted to demonstrate different subtypes of

this syndrome, but over time, this has been established only for

spikes located in the occipital region. Only in correlation with the

clinical description of seizures, two new types of epilepsy with

clear clinical-neurophysiological distinctions were recognized:

Gastaut's type and Panayiotopoulos' type of childhood occipital

epilepsy. According to the ILAE definition from 2022 [39],

Panayiotopoulos syndrome is called Self-limited epilepsy with

autonomic seizures, and Gastaut's type of occipital epilepsy is

called Childhood occipital visual epilepsy (COVE).

Panayiotopoulos then introduced the concept of the susceptibility

syndrome [35], a continuum of childhood benign focal epilepsies. The

concept consists of a unique nosological entity with phenotypic

variations. According to this concept, the central and largest part

is BECT, while at the milder end is Panayiotopoulos syndrome, and at

the other end is epilepsy with continuous discharges during sleep.

When it comes to the EEG findings, it has been observed that

identical spike-wave complexes seen in BECT also appear in children

without seizures. Genetic studies have shown that this trait is

inherited, but the type of inheritance and the responsible gene (or

genes) remain unknown. Many genes have been associated with this

trait [40], but there is no consensus on the inheritance pattern.

Inheritance has been found not to be gender-related since such

discharges in healthy children (children without seizures) occur

equally in boys and girls, unlike in BECT where there is a clear

male predisposition. It can be concluded that BECT discharges are a

necessary but not sufficient condition for the development of BECT.

Only the second one (gender-related inherited condition) allows

seizures to occur in children with predisposition (i.e. spike-wave

complexes in EEG).

The nature of the spike in EEG remains unknown. Despite advances in

medicine and science in general, it is still unclear which

neurophysiological processes in the brain lead to the appearance of

spikes in EEG.

Benign course

The third key characteristic of this syndrome is a favorable

prognosis, i.e., the resolution of seizures during development [16].

While crucial for the entity, from a clinician's perspective, this

characteristic lacks significant diagnostic value. It requires a

sufficiently long period to confirm the benign nature of the

epilepsy. Consequently, a definitive diagnosis can only be made

retrospectively, once the child outgrows the age when this epilepsy

occurs, and since this period is defined differently in the

literature, the final diagnosis can only be established after a

prolonged, vaguely defined period.

On the other hand, the favorable prognosis holds significant

prognostic value, for it reassures parents that their child's

epilepsy will likely resolve over time, making it crucial for

clinicians to have the first two elements present (clinical and EEG

findings) to determine the third (favorable course), similar to how,

in mathematics, two angles in a triangle can determine the third

one.

However, the concept of benignity has been reevaluated and has been

completely removed from the name following the ILAE recommendation

[39]. This action is based on numerous studies indicating various

changes in these children, mainly on a cognitive, behavioral, and

psychological level. These changes were detected through carefully

designed and precisely conducted studies, reaching statistical

significance. Since the term benignity could imply "insignificance"

across all aspects of this entity due to its broadness, it has been

replaced with the term "self-limited," indicating a time-limited

occurrence of seizures. In other words, by removing the term

"benign" from the name, the favorable course of epilepsy remains

acknowledged.

The term "benign" is eliminated from the title while retaining the

concept of a favorable course.

Classification

International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) provided a

classification of epileptic seizures in 1981 [41], and in 1989, they

published a classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes

[42]. Both classifications proved to be highly valuable for both

practitioners and researchers, operating at both clinical and

scientific levels.

The 1989 classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes [42]

lists two entities among idiopathic focal epilepsies of childhood:

Benign childhood epilepsy with centro-temporal spike

Childhood epilepsy with occipital paroxysms

In the report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and

Terminology in 2001 [38], presented by Engel, five axes were

proposed for diagnosing patients with epilepsy.

1. The first axis involves the description of seizures (ictal

semiology).

2. The second axis involves the type of epileptic seizure. The ILAE

Commission provided a list of accepted seizure types, categorized

into self-limited seizures, continuous seizures, further divided

into generalized and focal seizures.

3. The third axis is the syndromic diagnosis, including a list of

accepted epileptic syndromes.

4. The fourth axis consists of specific etiology when known.

5. The fifth axis is optional and relates to the degree of

impairment resulting from epilepsy.

Idiopathic childhood epilepsies (Axis 3), besides Benign Childhood

Epilepsy with Centrotemporal Spikes, recognize two additional

syndromes: Benign Childhood Occipital Epilepsy with Early Onset

(Panayiotopoulos type) and Childhood Occipital Epilepsy with Late

Onset (Gastaut type). It's notable that the term "benign" remains in

the name of two syndromes in this group of epilepsies.

In 2010, ILAE issued a revision of terminology and the concept of

organizing seizures and epilepsies [43]. The concept of

electroclinical syndrome was introduced, referring to complex

clinical data, signs, and symptoms that together define a distinct

and recognizable clinical disorder. There are specific disorders

identified by features such as the age of onset, specific EEG

findings, types of seizures, and other characteristics that, when

considered together, allow a specific diagnosis. A syndromic

diagnosis, in turn, impacts the treatment, management, and prognosis

of epilepsy.

The recommendation related to Rolandic epilepsy in this revision

pertains to the use of the term "Benign Epilepsy." The

recommendation is not to use the term "benign." The reasons are

manifold. Firstly, it has been shown that childhood focal benign

epilepsies are not as "benign" as initially thought. Increased

knowledge indicates a connection between epilepsy and a broad

spectrum of brain disorders such as cognitive, behavioral, and

psychiatric disorders. The term "benign" may mislead both

professionals and patients and their families to underestimate and

neglect these associated conditions. On the other hand, the term

"benign" has not been completely eliminated from the names of these

epileptic syndromes, so in the category of childhood electroclinical

syndromes, the following names have remained:

Panayiotopoulos syndromeBenign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS)

Late onset childhood occipital epilepsy (Gastaut type)

Epileptic encephalopathy with continuous spike-and-wave during sleep

(CSWS)

Landau-Kleffner syndrome (LKS)

In 2017, the ILAE introduced a new classification of epileptic

seizures [44] with an attempt to facilitate its use in clinical

practice [45]. This classification is operational (practical) and is

based on the 1981 classification and its expansion in 2010.

Significant progress in understanding epilepsy and its mechanisms

was summarized in a noteworthy classification, the first after the

one in 1989. This classification provides diagnostic guidelines for

clinicians divided into three steps: First, the diagnosis of the

type of epileptic seizure. The second step is determining the type

of epilepsy, including focal epilepsies, generalized epilepsies,

combined generalized and focal epilepsies, and the unknown epilepsy

group. The third step is determining the epileptic syndrome, where a

syndromic diagnosis can be established. Regarding the cause, instead

of the terms idiopathic, cryptogenic, and symptomatic, the etiology

of epilepsy can be (1) genetic, (2) structural, (3) metabolic, (4)

immunological, (5) infectious, and (6) unknown.

The term "benign" has been replaced with "self-limited" or "pharmacoresponsive."

This recommendation also extends to the name of the electroclinical

syndrome, so "Benign epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes" is now

called "self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes."

The change in the name of the most common childhood epilepsy after

decades of using the word "benign" as a key element in the name

stems from the imprecision of the term "benign." With the increased

knowledge about benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes

(BECT), it has been widely accepted that there are small but

statistically significant abnormalities in the cognitive, behavioral,

and emotional areas in children with this type of epilepsy.

Consequently, BECT is no longer entirely "benign," leading to the

replacement of the term "benign" with "self-limited." This new term

is more precise and clearly indicates one of the main

characteristics of this electroclinical syndrome, namely the

mandatory cessation of seizures upon entering adolescence (i.e.,

with the completion of nervous system maturation).

However, while gaining precision, there is a loss on the other side.

The name of this syndrome was already awkward and often replaced

with abbreviations, which, on the other hand, were not always

standardized. The term "self-limited" is not commonly used in

everyday language, requiring additional mental effort to understand

its meaning. Instead of one widely accepted word ("benign"), a

compound term ("self-limited") is introduced, usually requiring

further explanation. In the end, instead of a name consisting of

five words, we now have a name with six words. In the professional

community, confusion may arise, leading to the perception of a new

entity when encountering this term. The key word in the old name

("benign") is now missing and replaced by a new compound term

("self-limited").

Attempts to precisely define an entity in its name inevitably lead

to a name that can be awkward and unwieldy can create difficulties

in its acceptance in clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

The concept of epileptic syndromes and the dynamics of renaming

certain diseases depend on the rapid progress of scientific

knowledge in medicine. Recommendations from ILAE contribute to

terminology standardization and a better understanding of the

essence of epilepsy. Given the dynamic nature of this field, ILAE

will continue to monitor new achievements in epileptology and update

classifications to reflect the latest knowledge. Clinicians are

urged to not only formally but also substantively follow

developments in their medical field to provide the best and most

contemporary assistance to their patients.

LITERATURE:

- Specchio N, Wirrell EC, Scheffer IE, Nabbout R, Riney K,

Samia P et al. International League Against Epilepsy

classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset

in childhood: Position paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology

and Definitions. Epilepsia. 2022;63(6):1398-1442.

- van Huffelen AC. A Tribute to Martinus Rulandus: A

16th-Century Description of Benign Focal Epilepsy of Childhood.

Arch Neurol. 1989;46(4):445–447

- Beaussart. Benign epilepsy of children with Rolandic

(Centro-temporal) paroxysmal foci. Epilepsia. 1972; 13:795-811.

- Gibbs E, Gibbs F. Good Prognosis of Mid-Temporal Epilepsy.

Epilepsia.1959;1: 448-453.

- Lombroso C; Sylvian Seizures and Midtemporal Spike Foci in

Children. Arch Neurol, 1967, 17: 52-59.

- Beaussart M. Benign epilepsy of children with Rolandic (centro-temporal)

paroxysmal foci. A clinical entity. Study of 221 cases.

Epilepsia. 1972;13(6):795-811.

- Beaumanoir A, Ballis T, Varfis G, Ansari K. Benign epilepsy

of childhood with Rolandic spikes. A clinical,

electroencephalographic, and telencephalographic study.

Epilepsia. 1974; 15(3):301-15.

- Ambrosetto G, Gobbi G. Benign epilepsy of childhood with

Rolandic spikes, or a lesion? EEG during a seizure. Epilepsia.

1975;16(5):793-6.

- Beaussart M, Faou R. Evolution of epilepsy with rolandic

paroxysmal foci: a study of 324 cases. Epilepsia.

1978;19(4):337-42.

- Pan A, Gupta A, Wyllie E, Lüders H, Bingaman W. Benign focal

epileptiform discharges of childhood and hippocampal sclerosis.

Epilepsia. 2004;45(3):284-8.

- Altenmüller DM, Schulze-Bonhage A. Differentiating between

benign and less benign: epilepsy surgery in symptomatic frontal

lobe epilepsy associated with benign focal epileptiform

discharges of childhood. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(4):456-61.

- Wang F, Zheng H, Zhang X, Li Y, Gao Z, Wang Y, Liu X, Yao Y.

Successful surgery in lesional epilepsy secondary to posterior

quandrant ulegyria coexisting with benign childhood focal

epilepsy: A case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;149:94-7.

- RamachandranNair R, Ochi A, Benifla M, Rutka JT, Snead OC

3rd, Otsubo H. Benign epileptiform discharges in Rolandic region

with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: MEG, scalp and intracranial

EEG features. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116(1):59-64.

- Specchio N, Wirrell EC, Scheffer IE, Nabbout R, Riney K,

Samia P, et al. International League Against Epilepsy

classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset

in childhood: Position paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology

and Definitions. Epilepsia. 2022;63(6):1398-1442.

- Massa R, de Saint-Martin A, Carcangiu R, Rudolf G,

Seegmuller C, Kleitz C et al. EEG criteria predictive of

complicated evolution in idiopathic rolandic epilepsy.

Neurology. 2001;57(6):1071-9.

- Lerman P, Kivity S. Benign focal epilepsy of childhood. A

follow-up study of 100 recovered patients. Arch Neurol.

1975;32(4):261-4.

- Blom S, Heijbel J, Bergfors PG. Benign epilepsy of children

with centro-temporal EEG foci. Prevalence and follow-up study of

40 patients. Epilepsia. 1972;13(5):609-19.

- Loiseau P, Duché B, Cordova S, Dartigues JF, Cohadon S.

Prognosis of benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal

spikes: a follow-up study of 168 patients. Epilepsia.

1988;29(3):229-35.

- Santanelli P, Bureau M, Magaudda A, Gobbi G, Roger J. Benign

partial epilepsy with centrotemporal (or rolandic) spikes and

brain lesion. Epilepsia. 1989;30(2):182-8.

- Ambrosetto G, Tassinari CA. Antiepileptic drug treatment of

benign childhood epilepsy with rolandic spikes: is it necessary?

Epilepsia. 1990;31(6):802-5.

- Drury I, Beydoun A. Benign partial epilepsy of childhood

with monomorphic sharp waves in centrotemporal and other

locations. Epilepsia. 1991;32(5):662-7.

- Ambrosetto G. Unilateral opercular macrogyria and benign

childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal (rolandic) spikes: report

of a case. Epilepsia. 1992;33(3):499-503.

- Gelisse P, Genton P, Raybaud C, Thiry A, Pincemaille O.

Benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes and

hippocampal atrophy. Epilepsia. 1999;40(9):1312-5.

- Kelemen A. Benign epilepsy of childhood with malformations

of cortical development. Epilepsia. 2003;44(9):1259-60;

- Polychronopoulos P, Argyriou AA, Papapetropoulos S, Gourzis

P, Rigas G, Chroni E. Wilson's disease and benign epilepsy of

childhood with centrotemporal (rolandic) spikes. Epilepsy Behav.

2006;8(2):438-41.

- Iannetti P, Raucci U, Basile LA, Spalice A, Parisi P,

Fariello G, Imperato C. Benign epilepsy of childhood with

centrotemporal spikes and unilateral developmental opercular

dysplasia. Childs Nerv Syst. 1994;10(4):264-9.

- Shevell MI, Rosenblatt B, Watters GV, O'Gorman AM, Montes

JL. "Pseudo-BECRS": intracranial focal lesions suggestive of a

primary partial epilepsy syndrome. Pediatr Neurol.

1996;14(1):31-5.

- Sheth RD, Gutierrez AR, Riggs JE. Rolandic epilepsy and

cortical dysplasia: MRI correlation of epileptiform discharges.

Pediatr Neurol. 1997;17(2):177-9.

- Baumgartner C, Graf M, Doppelbauer A, Serles W, Lindinger G,

Olbrich A, et al. The functional organization of the interictal

spike complex in benign rolandic epilepsy. Epilepsia.

1996;37(12):1164-74.

- Panayiotopoulos CP, Michael M, Sanders S, Valeta T,

Koutroumanidis M. Benign childhood focal epilepsies: assessment

of established and newly recognized syndromes. Brain.

2008;131(Pt 9):2264-86.

- Fejerman N. Atypical rolandic epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50

Suppl 7:9-12.

- Bourel-Ponchel E, Mahmoudzadeh M, Adebimpe A, Wallois F.

Functional and Structural Network Disorganizations in Typical

Epilepsy With Centro-Temporal Spikes and Impact on Cognitive

Neurodevelopment. Front Neurol. 2019;10:809.

- An O, Nagae LM, Winesett SP. A Self-Limited Childhood

Epilepsy as Co-Incidental in Cerebral Palsy. Int Med Case Rep J.

2021;14:509-517.

- Panayiotopoulos CP.Panayiotopoulos Syndrome: A common and

benign childhood epileptic syndrome. London: John Libbey. 2002.

- Panayiotopoulos CP. Benign childhood partial epilepsies:

benign childhood seizure susceptibility syndromes. J Neurol

Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56(1):2-5.

- Bali B, Kull LL, Strug LJ, Clarke T, Murphy PL, Akman CI, et

al. Autosomal dominant inheritance of centrotemporal sharp waves

in rolandic epilepsy families. Epilepsia. 2007;48(12):2266-72.

- Gibbs EL, Gillen HW, Gibbs FA. Disappearance and migration

of epileptic foci in childhood. AMA Am J Dis Child.

1954;88(5):596-603

- Engel J Jr; International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE). A

proposed diagnostic scheme for people with epileptic seizures

and with epilepsy: report of the ILAE Task Force on

Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2001;42(6):796-803.

- Specchio N, Wirrell EC, Scheffer IE, Nabbout R, Riney K,

Samia P et al. International League Against Epilepsy

classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset

in childhood: Position paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology

and Definitions. Epilepsia. 2022;63(6):1398-1442.

- Xiong W, Zhou D. Progress in unraveling the genetic etiology

of rolandic epilepsy. Seizure. 2017;47:99-104.

- Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic

classification of epileptic seizures. From the Commission on

Classification and Terminology of the International League

Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1981;22(4):489-501.

- Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and

epileptic syndromes. Commission on Classification and

Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy.

Epilepsia. 1989;30(4):389-99.

- Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, Buchhalter J, Cross JH, van

Emde Boas W, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for

organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE

Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005-2009.

Epilepsia. 2010;51(4):676-85.

- Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, Connolly MB, French J,

Guilhoto L, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies:

Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and

Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):512-521.

- Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, Higurashi N, Hirsch E,

Jansen FE, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by

the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the

ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia.

2017;58(4):522-530.

|

|

|

|