| |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

The term "melanonychia" derives from the Greek words "Melas,"

meaning black or brown color, and "Onyx," meaning nail. It is

characterized by black-brown discoloration of the nail plate and

nail matrix epithelium caused by the accumulation of melanin. It can

affect one or more nail plates, both on the hands and feet. It

predominantly presents as a longitudinal black-brown streak starting

from the matrix and extending to the free edge of the nail plate.

Less commonly, the discoloration affects the entire nail plate or

manifests as a transverse band.

The black-brown discoloration is caused by the accumulation of

melanin produced by melanocytes in the nail matrix. Differentiation

includes simple melanocyte activation, benign, and malignant

melanocyte proliferation. Melanocyte activation can be induced by

iatrogenic agents, pathogenic microorganisms, nutritional deficits,

and trauma. Additionally, it can be present in certain physiological

conditions, abnormalities of the nail plate or periungual tissue,

dermatological conditions, tumors, systemic disorders, and

syndromes. Melanocyte proliferation includes lentigo, nail matrix

nevus, and subungual melanoma.

Melanonychia in childhood is rare. In adults, its prevalence varies

(from 0.8% to 23%). Diagnosis is based on history, physical

examination, onychoscopic examination, and biopsy with histological

examination. Treatment depends on the etiology and nature of

melanonychia.

CASE REPORT

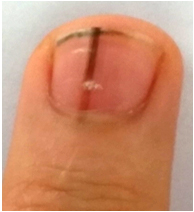

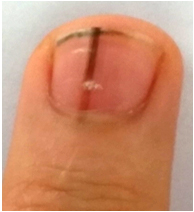

During a systematic examination of a 13-year-old boy, a single

black-brown, linear discoloration was observed on the index finger

of his left, non-dominant hand (See Figure 1). There was no nail

plate dystrophy, periungual pigmentation, or bleeding. The onset

time of the change could not be determined. The boy was healthy, and

his medical and family history were unremarkable. On onychoscopic

examination, brown-black, parallel, longitudinal lines were observed

on a brown background. The hyperpigmentation of the nail bed was

visible through a thin cuticle and the distal part of the proximal

nail fold. A diagnosis of nail matrix nevus was made, and regular

follow-up by a dermatologist was advised.

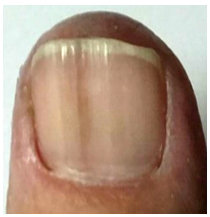

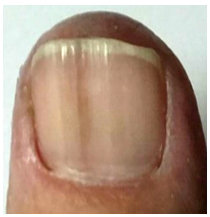

During a follow-up examination of a 59-year-old female patient, a

single melanonychia of the nail plate of the thumb of her right,

dominant hand was observed. It was a brown, linear, uniformly

pigmented, clearly demarcated discoloration with discreetly

irregular edges from the proximal nail fold to the free edge of the

nail plate. There were no signs of trauma, nail plate dystrophy, or

bleeding. The change had been present for several months without

altering in size or pigment intensity. The patient, a homemaker and

non-smoker, had cardiomyopathy, irregular heart rhythm, high blood

pressure, type 2 diabetes, and high cholesterol levels. She was on

continuous therapy with 200mg of amiodarone, 4mg of acenocoumarol,

20mg of enalapril, 1000mg of metformin, and 10mg of rosuvastatin. On

onychoscopic examination, brown-black longitudinal lines of varying

width were visible through the cuticle and proximal nail fold on a

brown background. A longitudinal excision biopsy was indicated,

revealing an increased number of heavily pigmented melanocytes

without signs of atypia in the basal epidermis. Thus, a diagnosis of

nail plate lentigo was made, and the patient was advised regular

dermatologist check-ups.

| Figure 1. Nail matrix nevus |

Figure 2. Lentigo of the nail

matrix |

|

|

DISCUSSION

Melanonychia implies nail pigmentation caused by simple

activation of nail matrix melanocytes, either benign (lentigo or

nail matrix nevus) or malignant (subungual melanoma) proliferation

of the same [1].

Simple melanocyte activation (melanocyte stimulation, functional

melanonychia) involves increased melanin production in secondarily

activated melanocytes without an increase in the number of

melanocytes [4].

Melanocytes are physiologically activated in ethnic melanonychia and

pregnancy [7]. Ethnic melanonychia is predominantly present in

individuals with darker pigmented skin types IV, V, and VI [1,7].

Its prevalence varies from 1% in Caucasians, 10%-20% in Asians, to

77–100% in African Americans [7]. It is most commonly found on the

thumb and index finger of the hand and the big toe [1,7]. It often

affects multiple nail plates, and its width increases with age

[1,7]. Melanocyte activation during pregnancy involves several nails

on the hands and/or feet [1]. It may disappear or persist after

childbirth [1].

Melanocyte activation caused by drugs is often accompanied by skin

and/or mucous membrane pigmentation [1]. Its form is variable

(transverse or longitudinal stripes, solitary or associated) [1].

The majority of transverse melanonychias are caused by drugs [1].

Often, the changes involve several nails and fade partially or

completely upon discontinuation of the drug [1,3]. Melanonychia can

be caused by antiretroviral drugs (lamivudine, zidovudine),

antimalarial drugs (mepacrine, amodiaquine, chloroquine, quinacrine),

anticancer drugs (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, hydroxyurea,

busulfan, taxanes, capecitabine, cisplatin, bleomycin, daunorubicin,

dacarbazine, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate) as well as simultaneous

use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs [1,2,3].

Melanocyte activation can also be induced by metals (arsenic,

thallium, mercury), biological agents (clofazimine, infliximab,

psoralen, phenytoin, fluconazole, cyclines, ketoconazole,

phenothiazines), ultraviolet therapy, electron beam therapy, and

conventional radiographic therapy (used in the 1950s and 1960s)

[1,3]. The same effect is produced by henna, tobacco, potassium

permanganate, tar, and silver nitrate [1].

Fungal melanocyte activation occurs as a result of onychomycosis,

fungal infection of the nail plate [9]. So far, at least 21

different species of fungi that can cause fungal melanonychia have

been described [9]. Its form is variable [1]. Dermatophytes (Scytalidium

dimidiatum) form longitudinal stripes, yeasts (Candida albicans,

Candida humicola, Candida parapsilosis) and molds (Trichophyton

rubrum, Alternaria, Exophiala) form diffuse discoloration [9,10].

With eradication of the causative agent, the appearance of the nail

plate usually normalizes [10,11]. The recurrence rate ranges from

10% to 50% [11].

Melanonychia can also be caused by gram-negative bacteria, including

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis

[1,12,13]. Immunocompromised states and working in a moist

environment are risk factors [1]. Longitudinal stripes with a wider

proximal edge or diffuse discolorations starting from the junction

of the proximal and lateral nail folds and spreading irregularly

along the medial edge are present on the nail plates [1].

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) predisposes to melanonychia

(diffuse discoloration, multiple longitudinal or transverse stripes

on multiple nail plates) accompanied by hyperpigmentation of the

mucous membranes, palms, and soles [14].

Dark brown discoloration of the nail plate is observed in

malnutrition (predominantly protein deficiency and vitamin D

deficiency) [1,15]. It is also present in the absence of vitamin B12

(often found in vegetarians) due to decreased glutathione

concentration and subsequent inhibition of tyrosinase, the main

enzyme of melanogenesis [16].

Repeated local trauma caused by uncomfortable footwear, occupational

trauma, onychophagia, onychotillomania, or carpal tunnel syndrome

can activate nail matrix melanocytes [1,13]. Traumatic melanonychia

is often accompanied by periungual signs of trauma [1]. Nail matrix

melanocytes are often activated in a variety of inflammatory

conditions and skin tumors, including Lichen planus, chronic

paronychia, psoriasis, amyloidosis, chronic radiation dermatitis,

Hallopeau acrodermatitis, myxoid pseudocyst, localized scleroderma,

onychomatrix, subungual linear keratosis, Verruca vulgaris,

subungual fibrous histiocytoma, Bowen's disease, basal cell

carcinoma, subungual fibrous histiocytoma [1,13,14].

Multiple dark brown stripes or diffuse discoloration on multiple

nail plates on the hands and feet are observed in Addison's disease,

Cushing's syndrome, hyperthyroidism, acromegaly, alkaptonuria,

hemosiderosis, hyperbilirubinemia, and porphyria [1]. Melanocyte

activation is also present in the host reaction against

transplantation (Graft versus host disease, GVHD) [1].

Laugier-Hunziker, Peutz-Jeghers, and Touraine syndromes are

characterized by multiple dark brown stripes on the nail plates

accompanied by pigmented mucous membrane macules on the lips and

oral cavity [1,3]. Laugier-Hunziker syndrome occurs sporadically in

white adults aged 20 to 40 years [1,3,18]. It does not have systemic

manifestations or malignant potential [1,3,18]. Peutz-Jeghers and

Touraine syndromes are predominantly present in children and are

inherited in an autosomal dominant manner [1,3,18]. They are

associated with intestinal polyps and an increased risk of

gastrointestinal and pancreatic malignancies [1,3,18].

Melanocytic hyperplasia involves an increase in the number of

melanocytes within the nail matrix [19,20]. We distinguish lentigo,

nail matrix nevus, and subungual melanoma [19,20].

Lentigo and nail matrix nevus are benign changes [20]. Lentigo is

melanocytic hyperplasia in the absence of melanocytic nests, usually

present in adults (9% of longitudinal melanonychias in adults)

[1,20]. Nail matrix nevus contains at least one melanocytic nest

[19,20]. It accounts for 12% of longitudinal melanonychias in adults

and 48% of longitudinal melanonychias in children [1]. We

distinguish congenital and acquired nevus [20]. In children,

especially under the age of 3, it is difficult to determine whether

the nevus is congenital or acquired, considering that nail matrix

nevus in the early stage can present as a colorless stripe [20].

In situ and invasive subungual melanoma belong to malignant

melanocytic hyperplasias [3]. Subungual melanoma is a rare form of

melanoma (1-3% of melanomas) [1]. The incidence varies among

different races (from 10% to 25%), with higher incidences observed

in Asian countries including Japan, China, and Korea [1]. There is

no significant difference in incidence by gender [20]. The peak

incidence is between the ages of 50 and 70 years [20]. Subungual

melanoma is usually localized on the thumb, big toe, and middle toe

[20]. In 38%-76% of cases, longitudinal melanonychia represents the

first manifestation of the disease [20].

The medical history includes gender, age, occupation, hobbies,

previous trauma, medical history, family medical history, continuous

therapy, time of onset of melanonychia, location of melanonychia,

color and width of the pigment strip, nail pain and/or bleeding, and

nail deformity/brittleness [20]. In pregnant women, it includes a

history of pregnancy and the relationship between pregnancy and the

onset or progression of melanonychia [20].

The physical examination requires careful assessment of all twenty

nails, skin, and mucous membranes [3]. During this examination, it

is necessary to determine the following:

- Is one or more nails involved?

- Does one nail differ from the others (if multiple nails are

involved)?

- Is the discoloration present on the surface, within, or beneath

the nail plate?

- Is the discoloration linearly oriented?

- Is the discoloration wider or darker proximally?

- Is the discoloration associated with nail plate dystrophy

(abrasion, splitting, cracking), periungual pigmentation, and

bleeding?

- Is the discoloration accompanied by changes in the skin and mucous

membranes? [1,3]

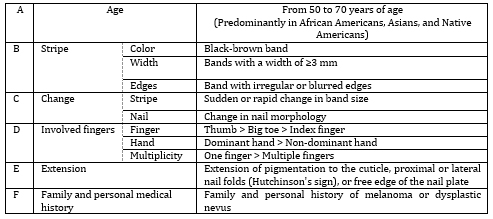

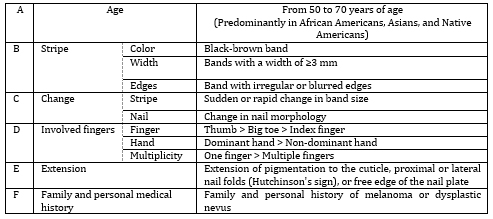

In the identification of subungual melanoma, the "ABCDE" (from

English: Age, Nail band, Change, Digit involved, Extension, Family)

rule established in 2000 by Levi and colleagues is applied (Table

1.) [20].

Table 1. ABCDEF rule of identification of

subungual melanoma

Nail plate onychoscopy (with handheld dermoscope and digital

videodermoscope) enables differentiation between melanin and

non-melanin pigmentation (subungual hematoma, pigmentation caused by

exogenous substances) [1,20]. Subungual hematoma is characterized by

beads of varying sizes and colors (ranging from bright red to brown

or black) depending on the depth and duration of bleeding [1]. It is

important to note that subungual bleeding does not exclude the

presence of subungual melanoma [1]. Additionally, Hutchinson's sign

(extension of pigmentation into the cuticle, proximal, or lateral

nail folds) of subungual melanoma and pseudo-Hutchinson's sign (hyperpigmentation

of the nail bed visible through the thin cuticle and distal part of

the proximal nail fold) should be distinguished [20,21].

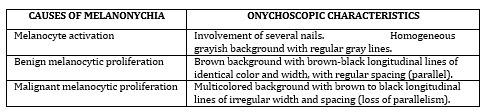

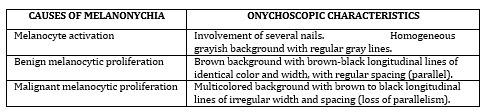

Onychoscopic patterns of melanocyte activation, benign, and

malignant proliferation have been convincingly confirmed in

scientific research (Table 2) [1,20,22].

Table 2. Onychoscopic characteristics in relation

to the cause of melanonychia 1

Intraoperative onychoscopy of the nail bed and matrix allows

direct visualization of the changes in the nail bed and matrix [1].

Additionally, it facilitates determining margins and complete

excision of the lesion [22].

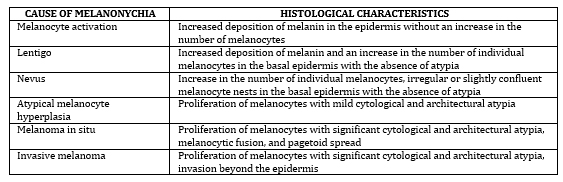

Biopsy represents the gold standard in the diagnosis of subungual

melanoma [6]. The type and location of the biopsy are determined by

the morphological characteristics of melanonychia [1].

Histologically, subungual melanoma is characterized by asymmetry,

infiltrative edges, significantly increased number of melanocytes in

the basal layer (up to 39-136/mm), tendency to form compact

aggregates in the suprabasal layers, presence of cytological atypia,

and inflammatory processes [13]. Malignant melanocytes are

multi-nucleated with large, atypical nuclei, exhibiting increased

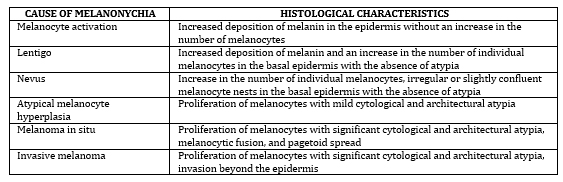

mitotic activity (Table 3).

Table 3. Histological characteristics in relation

to the cause of melanonychia

CONCLUSION

Melanonychia represents a complex clinical entity whose etiology

is often not easily determined. Simple activation of the nail matrix

melanocytes, lentigo, nevus, and subungual melanoma have similar

clinical characteristics, but their prognoses vary significantly.

Careful medical history, physical examination, onychoscopic

examination, and ultimately biopsy with histological examination

allow for early diagnosis of subungual melanoma as a fundamental

goal and precondition for successful treatment of the disease.

LITERATURE:

- Singal A, Bisherwal K. Melanonychia: Etiology, Diagnosis,

and Treatment. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020;11(1):1-11.

Dostupno

na:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7001389/

- Tosti A. Diseases of Hair and Nails. 450-Diseases of Hair

and Nails. Editors: Lee Goldman L, Schafer AI. Goldman's Cecil

Medicine (Twenty Fourth Edition). Saunders WB.2012:2551-2556.

Dostupno na:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/melanonychia

- Jefferson J, Rich P. Melanonychia. Dermatology Research and

Practice. 2012;952186. Dostupno na:

https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/952186

- Güneş P, Göktay F. Melanocytic Lesions of the Nail Unit.

Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5(3):98-107. Dostupno na:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6120410/

- Putri HA.A Case of Longitudinal Melanonychia in A Child:

Benign or Malignant? J Gen Proced Dermatol Venereol Indones.

2022:6(2);51-56. Dostupno na:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=/context/jdvi/article/1008/&path_info=9._CR_A_Case_of_Longitudinal_Melanonycia_

on_child__Benign_or_Malign_FINAL.pdf

- Quiroz Alfaro AJ, Greiffenstein J, Herrera Ortiz AF, Dussan

Tovar CA, Saldarriaga Santamaría S, Cifuentes Burbanoet J et al.

Incipient Melanonychia: Benign Finding or Occult Malignancy? A

Case Report of Subungual Melanoma. Cureus. 2023; 15(1):e34292.

Dostupno na:

https://www.cureus.com/articles/134276-incipient-melanonychia-benign-finding-or-occult-malignancy-a-case-report-of-subungual-melanoma#!/

- Lee DK, Lipner SE. Optimal diagnosis and management of

common nail disorders. Annals of Medicine.2022;54(1):694-712.

Dostupno na:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07853890.2022.2044511

- Cristián Fischer L, Matías Sanhueza M. Hiperpigmentación

cutánea y melanoniquia provocada por hidroxicloroquina: primer

caso reportado en Chile. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020. Dostupno

na: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2019.02.027

- Elmas ÖF, Metin MS. Dermoscopic findings of fungal

melanonychia. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020;37(2):180-183.

Dostupno na:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7262796/

- Cohen PR, Shurman J. Fungal Melanonychia as a Solitary Black

Linear Vertical Nail Plate Streak: Case Report and Literature

Review of Candida-Associated Longitudinal Melanonychia Striata.

Cureus. 2021;13(4):e14248. Dostupno na:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8093122/

- Westerberg DP, Voyack MJ. Onychomycosis: Current trends in

diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(11):762-70.

Dostupno na:

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2013/1201/p762.html

- Wu KY, Suh GA, Shi AY. Chronic Polymicrobial Infectious

Melanonychia Striata. JBJS case connector.2013;13(2). Dostupno

na:

https://mayoclinic.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/chronic-polymicrobial-infectious-melanonychia-striata

- Gradinaru TC, Mihai M, Beiu C, Tebeica T, Giurcaneanu C.

Melanonychia - Clues for a Correct Diagnosis. Cureus.

2020;12(1):e6621. Dostupno na:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7008765/

- Visuvanathan VV, Koh KC. Dark fingernails. Malays Fam

Physician. 2015;10(3):40-2. Dostupno na:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4992355/

- Seshadri D, De D. Nails in nutritional deficiencies. Indian

J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:237-241. Dostupno na:

https://ijdvl.com/nails-in-nutritional-deficiencies/

- Afra TP, Razmi TM, Narang T. Reversible Melanonychia

Revealing Nutritional Vitamin-B12 Deficiency. Indian Dermatol

Online J. 2020;11(5):847-848. Dostupno na:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7678521/

- Lalitha C, Shwetha S, Asha G S.Assessment of clinical and

etiological factors in nail dyschromias.Indian Journal of

Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 2021;7(4):324–330.

Dostupno na: https://www.ijced.org/html-article/15411

- Wang WM, Wang X, Duan N, Jiang HL, Huang XF.

Laugier–Hunziker syndrome: a report of three cases and

literature review. Int J Oral Sci.2012;4:226–230. Dostupno na:

https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2012.60

- Aseri J, Kumawat K, Tamta A, Bhargava P, Meena RS. Basic

approach to melanonychia: a review.Int J Res Dermatol.

2022;8(4):426-432. Dostupno na:

https://www.ijord.com/index.php/ijord/article/view/1566

- Cao Y, Han D.Longitudinal Melanonychia: How to Distinguish a

Malignant Condition from a Benign One. CJPRS. 2021;3(1):56-62.

Dostupno na:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2096691121000807

- Zhu M, Wang S, Wang P. Melanonychia with pseudo-Hutchinson

sign may assist in diagnosis of Addison's disease. Skin Res

Technol. 2023;29(8):e13441.Dostupno na:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10427615/

- Di Chiacchio N, Hirata SH, Enokihara MY, Michalany NS,

Fabbrocini G, Tosti A. Dermatologists' Accuracy in Early

Diagnosis of Melanoma of the Nail Matrix. Arch Dermatol.

2010;146(4):382–387. Dostupno na:

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/421241

- Anindya PH, Ennesta A, Qaira A. A Case of Longitudinal

Melanonychia in A Child: Benign or Malignant? Journal of

General-Procedural Dermatology & Venereology Indonesia.

2022;6(2):51-56. Dostupno na:

https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/jdvi/vol6/iss2/9?utm_source=scholarhub.ui.ac.id%2Fjdvi%2Fvol6%2Fiss2%2F9&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages

|

|

|

|