| |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

The primary characteristic of meteorism is the accumulation of

gases in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which causes a feeling of

bloating and abdominal distension. Meteorism and abdominal

distension are among the most common digestive issues that patients

experience at both primary and secondary care levels. Meteorism is a

very common symptom occurring in people of all ages, equally

prevalent in all races, and can be present in both babies and older

individuals. Approximately 15-23% of Asians and 15-30% of Americans

suffer from bloating [1,2]. In Slovenia, about 10-30% of the general

population have bloating problems [3].

This issue was highlighted in the past by the Persian physician

Avicenna in his Canon of Medicine. Avicenna used keywords such as

bloating and gases, attributing the causes of bloating to dietary

factors, inappropriate lifestyle, gastrointestinal, and other

reasons. Furthermore, Avicenna classified the causes based on the

location of origin, dividing them into the upper part of the abdomen

(stomach) and the intestinal part of the abdomen. He also listed 38

medicinal plants used as remedies. Modern scientific data support

most of the causes of bloating mentioned in Avicenna's Canon [4].

Symptoms of meteorism are even more prevalent in patients with

functional gastrointestinal disorders [5]. Meteorism is almost

invariably associated with symptoms such as bloating, distension,

and the passage of gas from the intestines. The causes of meteorism

are usually benign, such as overeating, swallowing air during meals,

or excessive fermentation in the intestinal microbiota. More

concerning causes may include bowel obstruction, kidney stones,

functional disorders related to overeating, bacterial overgrowth,

inflammatory bowel diseases, food intolerance, allergies, blunt

trauma to solid abdominal organs, peritonitis, and idiopathic

causes.

When defining functional disorders related to bloating, it is

crucial to exclude possible organic causes of symptoms, including

malignancies.

Diagnosis can involve many tests, including invasive ones, which may

pose a certain risk to the patient and a financial burden on the

healthcare system. Therefore, a step-by-step approach and targeted

treatment approach are necessary [3].

Meteorism and abdominal distension - definition of terms:

Meteorism, bloating, and distension are different terms used to

describe the same condition: increased gas in the digestive tract.

Meteorism is the medical term for this condition, while bloating and

distension are more common terms in everyday language. Bloating

refers to a feeling of tightness or fullness in the abdomen, while

distension refers to a visible increase in abdominal girth.

Flatulence is another medical term that refers to the passage of gas

from the anus.

In a healthy individual, the gastrointestinal tract usually contains

100 to 200 ml of gas, which is physiological and reflects the

dynamic process of gas formation during digestion. Gases can enter

the gastrointestinal tract during feeding (aerophagia), arise from

the breakdown of substances and bacterial fermentation. They are

eliminated during defecation, through the diffusion of gases from

the intestines into the systemic circulation, and some gases are

necessary for the metabolism of the intestinal microbiota. In

addition to causing discomfort, intestinal gases can be associated

with more serious symptoms. In the intestinal microbiota, bacteria

such as Bacteroides, Ruminococcus, Roseburia, Clostridium,

Eubacterium, Desulfovibrio, and Methanobrevibacter are among the

most common microbes responsible for the formation of intestinal

gases. More than 99% of intestinal gas consists of hydrogen, carbon

dioxide, and methane, while less than 1% consists of other odorous

compounds. Food groups associated with intestinal gases include

legumes, vegetables, fruits, cereals, and for some individuals,

dairy products. This food is rich in indigestible carbohydrates such

as oligosaccharides of the raffinose family, fructans, polyols, and

for sensitive individuals, lactose. These carbohydrates are

fermented by colonic bacteria, producing gases directly or through

cross-fermentation [8].

The composition of intestinal gases partly explains their origin:

nitrogen (N2) is usually from swallowed air; hydrogen (H2) is

produced by bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates; carbon dioxide

(CO2) is produced by bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates, fats,

and proteins; methane (CH4) is produced during anaerobic bacterial

metabolism. When there is an imbalance between gas production and

expulsion in the digestive system, it manifests as a feeling of

bloating with or without visible abdominal distension. A healthy

individual can tolerate up to 500 ml of air in the gastrointestinal

tract without major symptoms, but in patients with irritable bowel

syndrome, symptoms can be triggered by even minimal increases in gas

volume in the gastrointestinal tract [6,7].

Meteorism (bloating) is a symptom that patients describe as a

feeling of increased pressure in the abdominal cavity.

Simultaneously, abdominal distension may accompany it, wherein we

find an objectively increased volume of the abdomen; however,

abdominal distension can also occur as an independent sign [8,9].

Bloating and abdominal distension occasionally occur even in healthy

individuals as a result of normal digestion (especially after meals

rich in fats and fermentable sugars). The characteristic of

"physiological" bloating and distension is that they occur shortly

after meals, are short-lived, and disappear after urination or

passing gas. Initially, bloating and abdominal distension were only

understood as consequences of excessive air in the intestines.

Today, we know that the pathophysiology of both conditions is much

more complex and the result of different mechanisms. In addition to

increased gas production, which accumulates in the intestines along

with fluid, altered intestinal microbiota and functionally altered

enteric nervous system, which cause visceral hyperalgesia and

motility disorders [9,10].

The pathophysiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders with

meteorism and abdominal distension is multifactorial and not fully

understood. Several underlying mechanisms have been proposed that

may coexist in individual patients:

- Intraluminal content of the gut (increased gas and

fluid volume)

- Visceral hypersensitivity

- Abdominal-diaphragmatic dysenergia (Instead of the

relaxation of the diaphragm and contraction of the abdominal

walls, food intake leads to relaxation of the abdominal walls,

and the diaphragm moves lower and closer to the abdomen. This

leads to increased pressure in the abdominal cavity, which can

lead to meteorism, pain, and in some cases, constipation. ADD is

often seen together with pelvic floor muscle disinhibition.)

- Constipation

- Obesity

- Dysbiosis (leading to chronic inflammation, which

then leads to sensory and motor dysfunction)

- Psychogenic comorbidities (anxiety and depression)

[1,3]

These factors can interact and contribute to the development and

persistence of symptoms associated with meteorism and abdominal

distension.

Approach to patients with meteorism:

The etiology of meteorism and abdominal distension is highly

diverse, categorized into organic and functional causes. Diagnosis

is often demanding, prolonged, and costly.

Understanding the most common pathological conditions is essential

for the rational treatment of patients with meteorism. Patients can

be spared from many unpleasant and potentially risky examinations,

and prompt symptom improvement can be achieved through proper

disease recognition and treatment. When organic causes are ruled

out, particular attention must be paid to alarm symptoms. (Alarm

symptoms are indicators of possible organic diseases, and it is

necessary for a gastroenterologist to examine the patient as soon as

they are noticed. These symptoms include: sudden onset anemia due to

bleeding from the digestive tract, significant unintended weight

loss, persistent vomiting, difficulty swallowing, and the presence

of a palpable mass in the abdomen.) The presence of these signs with

bloating should prompt us to quickly perform endoscopic and imaging

diagnostics to rule out potential significant organic diseases.

Otherwise, endoscopic and imaging diagnostics often provide little

information when diagnosing the causes of functional meteorism

[7,10,11g.

Patient dietary habits are important in history taking. Consuming

large individual meals and fast eating can cause postprandial

bloating. Such patients are advised to eat smaller meals several

times a day. Additionally, certain foods can cause excessive

bloating: onions, legumes, coffee, carbonated beverages, or fruit

sugars [11]. In particular, these latter mentioned foods produce a

lot of gas during breakdown, which is the cause of the problem. This

knowledge formed the basis for the very popular "FODMAP" diet today.

The FODMAP diet is a dietary approach used to alleviate symptoms of

irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which include pain, bloating,

diarrhea, and constipation. FODMAP is an acronym for fermentable

oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols, which

are types of carbohydrates that some people cannot digest well. The

FODMAP diet reduces the intake of these substances and can help

reduce inflammation and gas production in the intestines. The FODMAP

diet is conducted in three phases: elimination, reintroduction, and

adaptation. In the first phase, all high-FODMAP foods are

eliminated, in the second phase, they are gradually reintroduced one

by one to determine which foods cause symptoms, and in the third

phase, the diet is adjusted based on individual tolerance. The

effectiveness of a diet avoiding fermentable oligo-, di-,

monosaccharides and polyols has been demonstrated in randomized

studies in patients with irritable bowel syndrome [12,13]. Dietary

history is also important for identifying possible diseases

resulting from the harmful effects of food on the gastrointestinal

system. Among them, lactose intolerance is the most common [14]. If

problems occur after consuming gluten in the diet, celiac disease

diagnosis is necessary [15]. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in

older individuals is not so rare [16].

Bloating can also result from certain medications, and it is one of

the side effects of metformin, while opioid analgesics can cause

both bloating and constipation simultaneously [11]. In the case of

constipation, there is disrupted stool and gas expulsion, which then

accumulate in the digestive tract. Up to 80% of patients report

bloating symptoms when they have constipation. In most patients,

bloating symptoms will disappear after resolving constipation [17].

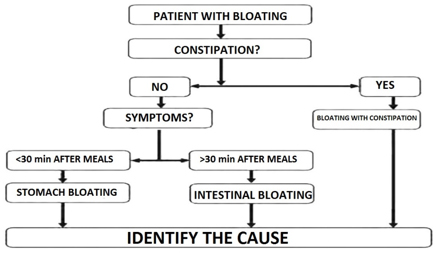

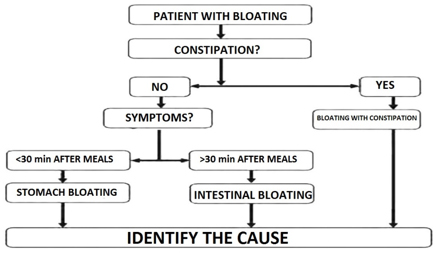

When further defining the causes of bloating, the timing of the

onset of symptoms can be helpful. If discomfort occurs shortly after

eating, the cause of bloating is usually in the upper

gastrointestinal tract – "gastric bloating." However, if a patient

reports bloating long after eating, the cause is usually lower in

the digestive tract - "intestinal bloating."

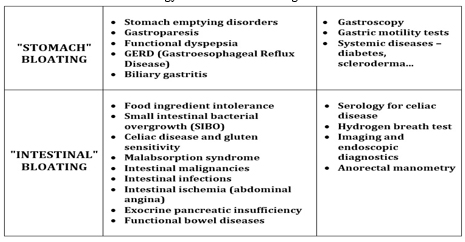

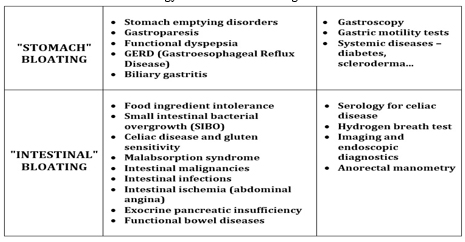

In summary: When "gastric" meteorism is present, we usually think of

disorders of gastric emptying, gastroparesis, functional dyspepsia,

GERD, or biliary gastritis. In this case, the most commonly used

diagnostic tools are gastroscopy or X-ray imaging of the upper GI

tract. If it is "intestinal" meteorism, we suspect intolerance to

food ingredients, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO),

celiac disease and gluten sensitivity, malabsorption syndrome, bowel

malignancy, intestinal infections, bowel ischemia (abdominal

angina), exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, or functional bowel

diseases. Diagnostic procedures include serological tests for celiac

disease, hydrogen breath test, imaging and endoscopic diagnostics,

and if necessary, anorectal manometry. A simplified algorithm for

the initial treatment of meteorism is summarized in Figure 1 [3].

Figure 1. Simplified procedure for the initial

treatment of a patient with flatulence

Table 1 shows some of the previously mentioned etiologically most

common conditions and common diagnostic procedures [3].

Table 1. Common etiology and some of the

diagnostic tests for flatulence

Certain more significant conditions that cause bloating

Among the more common causes of bloating are diseases due to altered

absorption of nutrients and food intolerances. The most common

causes of malabsorption can often be ruled out without invasive

interventions, even at the primary healthcare level. In recent

years, gluten-related diseases have become significant

gastrointestinal tract disorders. We must consider them, among other

reasons, because of their epidemiological dimensions. According to

some estimates, celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, and

wheat allergy affect up to 6% of the general population, and they

all share symptoms resulting from the harmful effects of gluten.

Introducing a gluten-free diet for most patients leads to objective

and subjective improvement of the disease [14,18].

Celiac disease

Celiac disease is a condition that should always be considered in

patients with bloating. It affects 1-2% of the population and is the

most common enteropathy. Special attention must be paid to it in all

age groups, especially in patients with type 1 diabetes and

Hashimoto's thyroiditis, where a lower threshold of suspicion for

testing should be maintained [18,19]. Serological diagnostics play a

role as a screening test, with the determination of IgA antibodies

against tissue transglutaminase (IgAtTG) being the first-choice

test. Despite the high specificity and sensitivity of serological

testing, it is not sufficient for diagnosing celiac disease in

adults. Confirmation through endoscopic examination and histological

examination of duodenal mucosa biopsy is necessary for a definitive

diagnosis. All patients with positive serological findings should be

referred for endoscopic diagnosis. Regardless of the serological

test result, endoscopic diagnosis is performed in patients with a

high probability of celiac disease. Patients with symptomatic

malabsorption, unexplained diarrhea with weight loss, unexplained

iron-deficiency anemia, herpetiform dermatitis, or symptomatic

patients who are first-degree relatives of celiac disease patients

fall into this category [19]. Serological testing and endoscopic

examination must be performed in patients following a

gluten-containing diet. If the patient is on a gluten-free diet at

the time of testing, they must be gluten-loaded. Recent studies have

shown that even small amounts of gluten can induce inflammation. The

gluten challenge should last at least 2 weeks, and if the patient

tolerates the diet, it can be extended up to 6 weeks [20,21].

Genetic testing for celiac disease may be used in patients already

on a gluten-free diet to determine the presence of HLA DQ2 and DQ8

alleles, which are necessary for celiac disease development; the

absence of these alleles excludes the disease with a probability of

over 99%. However, genetic testing is not used in routine practice

and is indicated for unclear forms of celiac disease and diagnosing

refractory forms of the disease [21].

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) has emerged as a separate

nosological entity in recent years. Symptoms are varied and similar

to those of celiac disease and other functional gastrointestinal

disorders, associated with gluten consumption. Since the mechanism

of the disease is poorly understood, there is still no diagnostic

biomarker. Therefore, the diagnosis of non-celiac gluten sensitivity

is made by excluding celiac disease. Wheat allergy, on the other

hand, results from a classic allergic reaction (type 1

hypersensitivity) to proteins contained in wheat, including gluten.

When antigens enter the body, the allergy can affect the skin,

respiratory system, or digestive system. Gastrointestinal symptoms

are nonspecific, including bloating, distension, diarrhea, but

allergic reactions can also manifest as anaphylaxis. The diagnosis

involves excluding celiac disease through serological testing and,

if indicated, performing endoscopic examination and

histopathological examination of duodenal mucosa biopsy. Allergy to

wheat is confirmed through skin prick tests or by determining

specific antibodies [23].

A gluten-free diet is crucial in gluten-related diseases. It

involves eliminating all foods containing wheat, rye, barley, and

related grains. Compared to a normal diet, a gluten-free diet is

more expensive and less accessible. Patients must also pay close

attention to hidden sources of gluten, as it appears in various

sauces, soups, processed seafood, dried meat products, and

dressings. Additionally, the managing physician must be aware that a

gluten-free diet is not always balanced, and the patient may consume

insufficient fiber, B-complex vitamins, iron, and trace elements

(zinc, copper, selenium...) [24,25]. Celiac disease is a chronic,

lifelong condition that, if left untreated, can lead to many serious

complications (osteoporosis, the development of other autoimmune

diseases, T-cell lymphoma). Therefore, strict lifelong dietary

adherence is the cornerstone of therapy. A gluten-free diet in

patients with celiac disease reduces symptom occurrence, improves

quality of life, enhances nutritional status, and prevents disease

complications. Symptoms disappear within 2-4 weeks, serological

tests normalize within weeks to months, and the mucosa completely

regenerates after about a year. Measurement of antibodies specific

to celiac disease is the most suitable test for assessing patient

compliance with a gluten-free diet. If after 6-12 months of strict

gluten-free diet, antibody levels in blood cells normalize but the

patient still reports symptoms, further evaluation by a dietitian

and gastroenterologist is required. It is necessary to exclude

gluten contamination, refractory forms of the disease, or possible

accompanying pathology [18,20,22].

A gluten-free diet is also the foundation of treatment for

non-celiac gluten sensitivity. The goal is symptom remission and

subjective well-being of the patient. Currently, there are no clear

recommendations regarding the necessity of a lifelong gluten-free

diet in these patients. There is insufficient research on whether

non-celiac gluten sensitivity is only transient or a chronic disease

state [18].

Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) is a common and often

overlooked cause of bloating, especially in older individuals. The

causes of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency are divided into

pancreatic or primary and non-pancreatic or secondary. In practice,

elastase determination in stool is used in diagnostics, but lately,

secretin MRCP (with much higher sensitivity and specificity) has

been employed. PEI significantly reduces the quality of life and is

diagnosed through clinical presentation and pancreatic function

tests. Treatment involves lifestyle adjustments, vitamin

supplementation, and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.

Long-term goals include eliminating clinical symptoms and correcting

malnutrition, addressing only the underlying disease when present.

Enzyme replacement therapy has both diagnostic and therapeutic

significance and leads to significant symptom improvement and better

quality of life for patients [26].

The treatment of meteorism and abdominal distension caused by

functional disorders, after excluding alarm signs and organic

diseases, involves gradual, individualized treatment. Patients with

mild functional bloating may only require reassurance that the

condition is benign, well, and not indicative of any

life-threatening disease.

Symptomatic treatment - Several agents are available for

treating these disorders. Antispasmodics have shown some clinical

benefit in alleviating symptoms in some patients [27]. Simethicone

has been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of meteorism,

distension, and bloating [28,29]. Peppermint oil reduced abdominal

distension compared to placebo [30,31]. Despite their popularity,

evidence is lacking regarding other commonly used agents such as

activated charcoal, Iberogast, and magnesium salts.

Dietary intervention - The role of dietary therapy in

managing bloating symptoms is crucial and is generally introduced

early in the treatment plan. The main reason for dietary therapy is

to identify foods that the patient does not tolerate and thus reduce

excessive fermentation of food residues. Initially, empirical

lactose and other poorly absorbed carbohydrate restrictions may be

implemented [12]. Alternatively, FODMAP diet or other elimination

diets may be offered to patients with meteorism and abdominal

distension if they have not improved on a restrictive diet [32].

Addressing constipation - Patients with chronic idiopathic

constipation (CIC) and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation

(IBS-C) usually report bloating in their medical history.

Lubiprostone has been found to reduce bloating in two

placebo-controlled clinical trials involving patients with IBS-C

[16,34]. Prucalopride, a selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist, enhances

spontaneous bowel movements and reduces bloating [35]. Similarly,

linaclotide, a guanylate cyclase C agonist, improves constipation

symptoms and reduces abdominal pain and bloating in patients with

CIC and IBS-C [36-42].

Microbiota modulation - Reducing gas-producing bacteria or

inducing changes in their metabolic activities may reduce excessive

fermentation and bloating. Rifaximin, a poorly absorbed

broad-spectrum antibiotic, has been found to reduce bloating and

flatulence in controlled trials in patients with and without IBS

[45,46]. Probiotics may become a therapeutic option in FABD;

however, studies have yielded different results, likely due to the

lack of standardized study methods [47,48]. A recent review

suggested that probiotics have a role in the treatment of functional

gastrointestinal disorders [49]. In a double-blind study, Ringel et

al. found that Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis

Bi-07 reduced bloating in patients with functional gastrointestinal

disorders without constipation [50].

Abdominal biofeedback therapy - As described, postprandial

meteorism and abdominal distension may result from abnormal

relaxation of the anterior abdominal wall and diaphragmatic

contraction. It has been shown that patients can be educated to use

their abdominal and diaphragmatic muscles to reduce discomfort

associated with meteorism and abdominal distension [51].

Modulation of the brain-gut axis - If heightened perception

of bowel wall stretching and visceral hypersensitivity are key

components in the pathogenesis of functional gastrointestinal

disorders with meteorism and abdominal distension, then modulation

of the brain-gut axis appears to be a reasonable treatment option.

The efficacy of antidepressants, such as tricyclic antidepressants (TCA)

and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), has been

evaluated in patients with IBS. In a small, controlled crossover

study, citalopram (SSRI) showed an increase in the number of days

without bloating after 3 and 6 weeks. In another study, desipramine

in combination with cognitive-behavioral therapy reduced bloating.

Hypnotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy, also offered to

patients with IBS, may be effective in patients with functional

gastrointestinal disorders [55].

CONCLUSION

Meteorism and abdominal distension represent a common clinical

problem. Like any other health condition, the clinical assessment of

gastrointestinal disorders with meteorism and abdominal distension

begins with a detailed medical history, physical examination, and

appropriate diagnostic tests. It is crucial to exclude any organic

cause of bloating and distension. Alarm symptoms, which may indicate

more serious pathology, should not be overlooked. Depending on the

frequency, gluten-related diseases should always be considered, and

in the elderly, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency should also be

considered. Celiac disease can be sufficiently excluded with

serological testing, even at the level of primary or secondary

medical facilities. In treatment, a gradual, multidisciplinary,

individualized approach is desirable. Therapy may target bowel

motility, muscle tone, microbiota, visceral sensitivity, nutrition,

and/or psychological comorbidities. Additionally, an "ex juvantibus"

response to treatment – improvement of symptoms with pancreatic

enzyme replacement therapy – indicates pancreatic exocrine

insufficiency.

LITERATURA:

- Lacy BE, Gabbard SL, Crowell MD. Pathophysiology,

evaluation, and treatment of bloating: hope, hype, or hot air?

Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7(11):729-39.

- Tuteja AK, Talley NJ, Joos SK, Tolman KG, Hickam

DH.Abdominal bloating in employed adults: prevalence,

riskfactors, and association with other bowel disorders. Am

JGastroenterol 2008;103:1241–48.

- Rado Janša Meteorizem, abdominalna distenzija,flatulenca

Gastroenterolog 2018;suplement 3:32–38.

- Naseri M, Babaeian M, Ghaffari F, Kamalinejad M, Feizi A, et

al. Bloating: Avicenna's Perspective and Modern Medicine. J Evid

Based Complementary Altern Med. 2016;21(2):154-9.

- Iovino P, Bucci C, Tremolaterra F, Santonicola A,

ChiarioniG. Bloating and functional gastro-intestinal disorders:

Whereare we and where are we going? World J

Gastroenterol.2014;20:14407–19.

- Mutuyemungu E, Singh M, Liu S, RoseDJ. Intestinal gas

production by the gut microbiota: A review Journal of Functional

Foods Volume 100, January 2023.Dostupno

na:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1756464622004376

preuzeto 22.02.2024)

- Serra J, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR: Impaired transit and

tol-erance of intestinal gas in the irritable bowel syndrome.

Gut2001;48:14–19.

- Malagelada JR, Accarino A, Azpiroz F. Bloating andAbdominal

Distension: Old Misconceptions and CurrentKnowledge. The

American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2017;112:1221–31.

- Drossman DA . Functional gastrointestinal disorders:

history,pathophysiology, clinical features, and rome

IV.Gastroenterology 2016;150:1262–79.

- Lacy E et all Management of Chronic Abdominal Distension and

Bloating Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology CrossrefDOI

link:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2020.03.056. Published Print:

2021-02

- Cotter TG, Gurney M, Loftus CG. Gas and Bloating—Controlling

Emissions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2016; 91:1105–13.

- Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG.A diet

low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritablebowel syndrome.

Gastroenterology 2014;146:67–9.

- Böhn L, Störsrud S, Liljebo T, Collin L, Lindfors P,Törnblom

H, et al. Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptomsof irritable bowel

syndrome as well as traditional dietaryadvice: a randomized

controlled trial. Gastroenterology2015;149:1399–407.

- Deng Y, Misselwitz B, Dai N, Fox M. Lactose Intolerance

inAdults: Biological Mechanism and Dietary Management.Nutrients

2015;7:8020–35.

- Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, et al. Spectrum of

gluten-relateddisorders: consensus on new nomenclature and

classifica-tion. BMC Medicine 2012; 10:13.

- Löhr M, Oliver M, Frulloni L. Synopsis of recent

guidelineson pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. United

EuropeanGastroenterology Journal 2013; 1:279–83.

- Iovino P, Bucci C, Tremolaterra F, Santonicola A,

ChiarioniG. Bloating and functional gastro-intestinal disorders:

Whereare we and where are we going? World J Gastroenterol.2014;

20: 14407–19.

- Elli L, Branchi F, Tomba C, et al. Diagnosis of

glutenrelated disorders: Celiac disease, wheat allergy and

non-celiac gluten sensitivity. World J Gastroenterol 2015;

21:7110–19.

- Snyder MR, Murray JA. Celiac disease: advances in

diagnosis.Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2016; 12:

449–63.

- Leffler D, Schuppan D, Pallav K, Najarian R, GoldsmithJD,

Hansen J, et al. Kinetics of the histological, serologicaland

symptomatic responses to gluten challenge in adultswith coeliac

disease. Gut 2013; 62: 996–1004.

- Kaswala DH, Veeraraghavan G, Kelly CP, Leffler DA.

CeliacDisease: Diagnostic Standards and Dilemmas. Diseases2015;

3: 86–101.

- Elli L, Villalta D, Roncoroni L, Barisani D, Ferrero

S,Pellegrini N, et al. Nomenclature and diagnosis of

gluten-related disorders: A position statement by the

ItalianAssociation of Hospital Gastroenterologists and

Endoscopists(AIGO). Digestive and Liver Disease 2017; 49:

138–46.

- Pasha I, Saeed F, Sultan MT, Batool R, Aziz M, Ahmed W.Wheat

Allergy and Intolerence; Recent Updates andPerspectives.

Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition2016; 56: 13–24.

- Krigel A, Lebwohl B Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity. Advancesin

Nutrition: An International Review Journal. 2016; 7:1105–10.

- Mulder CJJ, van Wanrooij RLJ, Bakker SF, Wierdsma N,Bouma G.

Gluten-Free Diet in Gluten-Related DisordersDigestive Diseases.

2013; 31: 57-62.

- Mari, A., Abu Backer, F., Mahamid, M. et al. Bloating and

Abdominal Distension: Clinical Approach and Management. Adv

Ther2019;36: 1075–1084.

- Barba E, Quiroga S, Accarino A, et al. Mechanisms of

abdominal distension in severe intestinal dysmotility:

abdomino-thoracic response to gut retention. Neurogastroenterol

Motil. 2013;25(6):e389–e394. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12128. )

- Maxton DG, Whorwell PJ. Abdominal distension in irritable

bowel syndrome: the patient’s perception. Eur Hepatol.

1992;4:241–243.

- Lewis M. Ambulatory abdominal inductance plethysmography:

towards objective assessment of abdominal distension in

irritable bowel syndrome.Gut. 2001;48(2):216–220. doi:

10.1136/gut.48.2.216.

- Dukowicz AC, Lacy BE, Levine GM. Small intestinal bacterial

overgrowth: a comprehensive review. Gastroenterol Hepatol.

2007;3:112–122.

- Bernstein J, Kasich A. A double-blind trial of simethicone

in functional disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J

Clin Pharmacol.1974;14(11):617–623. doi:

10.1002/j.1552-4604.1974.tb01382.x.

- Liu J, Chen G, Yeh H, Huang C, Poon S. Enteric-coated

peppermint-oil capsules in the treatment of irritable bowel

syndrome: a prospective, randomized trial. J Gastroenterol.

1997;32(6):765–768. doi: 10.1007/BF02936952.

- Cappello G, Spezzaferro M, Grossi L, Manzoli L, Marzio L.

Peppermint oil (Mintoil®) in the treatment of irritable bowel

syndrome: a prospective double blind placebo-controlled

randomized trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39(6):530–536. doi:

10.1016/j.dld.2007.02.006.

- Halmos E, Power V, Shepherd S, Gibson P, Muir J. A diet low

in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome.

Gastroenterology.2014;146(1):67–75. doi:

10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.046.

- Catassi G, Lionetti E, Gatti S, Catassi C. The low FODMAP

diet: many question marks for a catchy acronym. Nutrients.

2017;9(3):292. doi: 10.3390/nu9030292. (PMC free article)

- Camilleri M, Bharucha A, Ueno R, et al. Effect of a

selective chloride channel activator, lubiprostone, on

gastrointestinal transit, gastric sensory, and motor functions

in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol.

2006;290(5):G942–G947. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00264.2005.

- Tack J, Stanghellini V, Dubois D, Joseph A, Vandeplassche L,

Kerstens R. Effect of prucalopride on symptoms of chronic

constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;26(1):21–27. doi:

10.1111/nmo.12217.

- Castro J, Harrington A, Hughes P, et al. Linaclotide

inhibits colonic nociceptors and relieves abdominal pain via

guanylate cyclase-C and extracellular cyclic guanosine

3′,5′-monophosphate. Gastroenterology.2013;145(6):1334–1346.e11.

doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.017.

- Limbo AJ, Schneier HA, Shiff SJ, et al. Two randomized

trials of linaclotide for chronic constipation. N Engl J Med.

2011;365:527–536. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010863.

- Lacy BE, Schey R, Shiff SJ, et al. Linaclotide in chronic

idiopathic constipation patients with moderate to severe

abdominal bloating: a randomized, controlled trial. PLoS One.

2015;10:e0134349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134349.

- Videlock E, Cheng V, Cremonini F. Effects of linaclotide in

patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation or

chronic constipation: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 2013;11(9):1084–1092.e3. doi:

10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.032.

- Caldarella M, Serra J, Azpiroz F, Malagelada J. Prokinetic

effects in patients with intestinal gas retention.

Gastroenterology. 2002;122(7):1748–1755. doi:

10.1053/gast.2002.33658

- Accarino A, Perez F, Azpiroz F, Quiroga S, Malagelada J.

Intestinal gas and bloating: effect of prokinetic stimulation.

Am J Gastroenterol.2008;103(8):2036–2042. doi:

10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01866.x.

- Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey W, et al. Rifaximin therapy for

patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N

Engl J Med.2011;364(1):22–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004409.

- Sharara A, Aoun E, Abdul-Baki H, Mounzer R, Sidani S, ElHajj

I. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of

rifaximin in patients with abdominal bloating and flatulence. Am

J Gastroenterol.2006;101(2):326–333. doi:

10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00458.x.

- Moayyedi P, Ford A, Talley N, et al. The efficacy of

probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a

systematic review. Gut. 2008;59(3):325–332. doi:

10.1136/gut.2008.167270.

- Jonkers D, Stockbrügger R. Review article: probiotics in

gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

2007;26:133–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03480.x.

- Ringel Y, Carroll I. Alterations in the intestinal

microbiota and functional bowel symptoms. Gastrointest Endosc

Clin N Am. 2009;19(1):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2008.12.004.

- Ringel-Kulka T, Palsson O, Maier D, et al. Probiotic

bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium

lactis bi-07 versus placebo for the symptoms of bloating in

patients with functional bowel disorders. J Clin

Gastroenterol.2011;45(6):518–525. doi:

10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820ca4d6.

- Barba E, Burri E, Accarino A, et al. Abdominothoracic

mechanisms of functional abdominal distension and correction by

biofeedback. Gastroenterology.2015;148(4):732–739. doi:

10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.006. (PubMed)

- Tack J. A controlled crossover study of the selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram in irritable bowel

syndrome. Gut.2005;55(8):1095–1103. doi:

10.1136/gut.2005.077503.

- Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Efficacy and tolerability

of Hypericum perforatum in major depressive disorder in

comparison with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a

meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol

Psychiatry.2009;33(1):118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.10.018.

- Drossman D, Toner B, Whitehead W, et al.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus education and desipramine

versus placebo for moderate to severe functional bowel

disorders. Gastroenterology.2003;125(1):19–31. doi:

10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00669-3.

- Schmulson M, Chang L. Review article: the treatment of

functional abdominal bloating and distension. Aliment Pharmacol

Ther.2011;33(10):1071–1086. doi:

10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04637.x.

|

|

|

|