| |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

The use of a medicinal product in accordance with the marketing

authorization, which defines the formulation, dosage, age, and

issued by the relevant regulatory body, is called the use of the

medicinal product in accordance with the on-label marketing

authorization. The purpose of authorizing a medicinal product is to

ensure that the medicinal product is tested for its efficacy, safety

and quality. When the drug is prescribed outside the examined

indications, the therapy may be less safe, effective and reliable,

because it is based exclusively on assumptions and extrapolation.

The justification for prescribing these drugs, especially in the

pediatric population, due to the large differences between children

and adults, even between children of different ages, in terms of

pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic responses to the drug, is being

examined.

Recently, the use of a drug that does not comply with the approved

guidelines related to the indication, age, dosage regime or route of

administration is becoming more common. Off-label use of drugs

includes the use of drugs in higher or lower doses, use for

indications not described in the summary of product characteristics,

use in children outside the range of years defined by the license,

use of alternative routes of administration and use of drugs in

indications when contraindicated for a given drug. The use of

off-label drugs is mainly related to prevention, diagnosis or

therapeutic measures that are in accordance with the relevant

legislation, with the primary goal of improving or improving the

health condition.

Off-label use of drugs should be distinguished from the use of drugs

without a license (off-license). Unlicensed use of drugs is

considered to be the use of a drug that is not registered in the

Republic of Serbia, but is in other countries, or that is

registered, but it should be translated into another formulation or

drug that is not registered (eg. for the treatment of rare

diseases). Unregistered medicines are medicines that have not been

approved by the regulatory body for marketing. Off-label use is

considered to be the use of a drug in a way different from the

manner described in the marketing authorization: use of the drug for

the treatment of an indication not listed in the summary of product

characteristics, use of the drug in the age group outside the

permitted range, use of the drug doses of the drug characteristics

listed in the summary.

The most common reasons for the use of unregistered drugs are

modifications of registered drugs (crushing the tablet to form a

suspension), drugs that are registered for use in adults, but the

formulation for use in pediatrics requires a special drug permit

(adult drug is used in minor doses for children), new drugs that

require special permission from the manufacturer (eg. caffeine

injection used in case of apnea due to lung immaturity). Use of

drugs outside the marketing authorization includes the use of drugs

in higher or lower doses, use for indications not described in the

summary of product characteristics, use in children outside the age

range defined by the license, use of alternative routes of

administration and use of drugs in indications when contraindicated

allow for a given drug.

Modern use of drugs in the treatment of diseases of children and

newborns is increasingly based on the use of off-label drugs due to

lack of adequate formulations for the pediatric population, lack of

appropriate therapeutic parallels for the treatment of children and

almost no clinical trials involving the pediatric population [1-4].

The thalidomide catastrophe (phocomelia in newborns) and the effect

of the use of chloramphenicol in children (gray baby syndrome)

initiated the process of testing and registration of drugs [5]. The

main goal of drug registration is to ensure that the drug is

quality, safe and effective. Unfortunately, large number of

medicines for children do not have a marketing authorization or

marketing authorization [6]. This suggests that for many drugs used

in children, evidence derived from pharmacokinetics, adequate

dosing, or formulation-related studies is lacking [7,8]. Focusing on

other factors influencing the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

of drug dosing has received little attention during drug development

in children. As a result, many drugs have been used outside of their

licensed recommendations, commonly known as off-label prescribing,

which has become an increasingly common prescribing trend in

children. Over-the-counter prescribing for children is widespread

mainly in systemically administered drugs, but also in locally

applied drugs [9].

Several factors leading to off-label prescribing in children have

been identified in the past. Subsequently, legislative, regulatory,

governmental, and professional initiatives were introduced and

implemented globally to obtain better data on the effects of drugs

on children and consequently to instruct health professionals to use

quality drugs that are effective for children and do not cause harm

when used. Initiatives to improve drug use in children were first

implemented in the United States from 1994 to early 2000. [10-13].

Almost a decade later, other countries (European Union, Canada,

Australia, Japan, China and Korea) as well as international

institutions (World Health Organization and the International

Council for the Harmonization of Technical Requirements for

Pharmaceutical Medicines for Human Use) have joined [14]. Data from

the literature show that most initiatives taken in the past have

been aimed at encouraging increased research on the use of drugs in

children, in order to improve the registration process and enable

the safe use of drugs in the pediatric population.

However, despite numerous global initiatives, the number of clinical

trials conducted in children is still insufficient, ie. the use of

drugs in children is rarely based on evidence from clinical trials

[15].

The aim of this study is to provide an overview of the global trend

and prevalence of prescribing off-label drugs from 1996 to 2016, and

to suggest future directions related to studies related to off-label

prescribing in children.

METHODOLOGY

Data collection was performed by electronic search of the PubMed

index database and Google Scholar. The literature search and

selection protocol has been defined using the PRIZMA method [16].

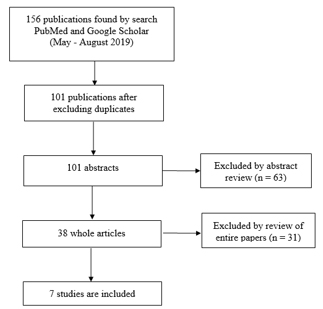

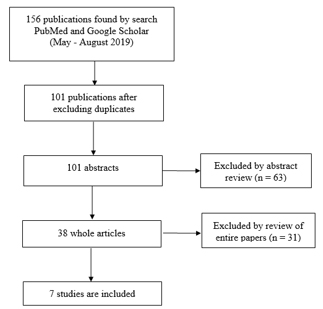

The corresponding flow diagram is graphically shown in Figure 1. The

search was performed in the period from May to August 2019. Selected

and presented in the paper are studies published in the period from

1996 to 2015. Searched keywords are: off label drug, pediatric

medicine, use in pediatrics. Original research was included which

provided data on the extent of use of off-label and unlicensed drugs

in the pediatric population as well as one systematic review.

Criteria for inclusion were: 1) published texts in full text in the

period from January 1996 to December 2016; 2) articles in Serbian

and English; 3) studies showing data on the results of the

prevalence of prescribing drugs outside the use permit for children;

4) off label use of cardiac, respiratory, antiallergic, oncological,

analgesic drugs and antibiotics

Exclusion criteria were: 1) notes and conferences; 2) off label use

of other therapeutic groups of drugs. The title and summary of the

articles have been carefully examined to determine the inclusion of

the study in this review. The following information was extracted

from the eligible studies: 1) study identification; 2) study details

(study design, setting, study period, method); 3) defining off-label

drug administration; 4) source references; 5) quantification of

outcomes; 6) results

Figure 1. PRIZMA diagram

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

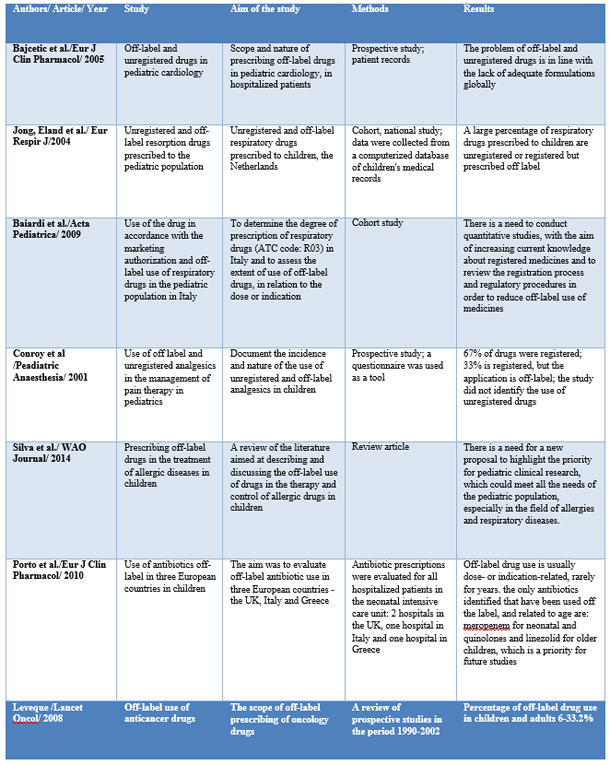

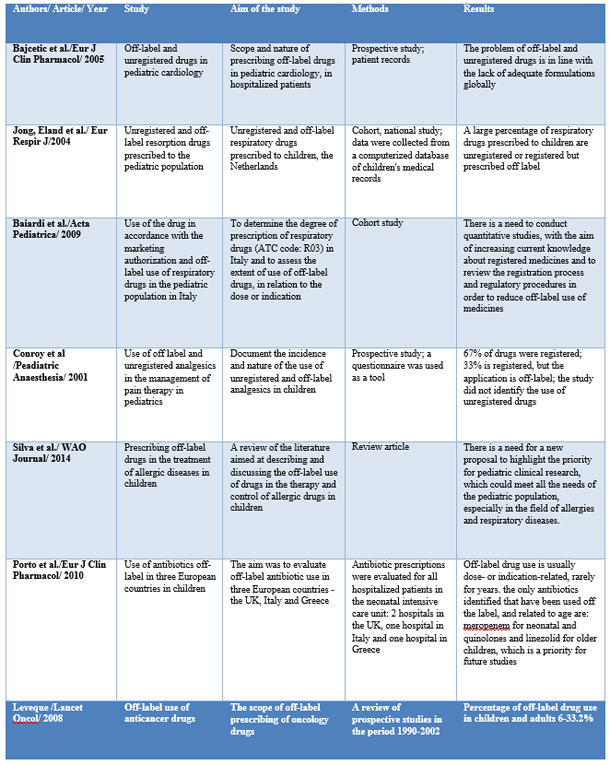

During the research, 101 studies were identified, of which 7 were

presented in this article, with the aim of presenting off-label use

of drugs in different therapeutic groups: cardiac, respiratory,

antiallergic drugs, antibiotics, oncology drugs and analgesics.

In a study conducted at the Department of Pediatric Cardiology, 544

patients participated in the University Children's Hospital in

Belgrade and included 2,037 prescriptions, with 102 different drugs,

of which 41% were registered drugs, 11% unregistered and 47%

prescribed drugs. off -label. Drugs are prescribed off-label: due to

age 21% and due to a different dose 26%. The largest number of

unregistered and off-label drugs (72%) is prescribed to children

aged between 2-11 years. Katopil is the only registered ACE

inhibitor for use in the pediatric population and is one of the most

prescribed drugs in this study, with one-third of prescriptions

being prescribed off-label in relation to the dose of katopil [17].

In a national cohort study conducted in Italy, in the period

2002-2006, medical records of children under 14 years of age were

analyzed, and the degree of prescribing drugs belonging to the ATC

code R03 - ß mimetics, inhaled glucocorticoids, inhaled

anticholinergics, combined formulations, antiallergic drugs,

xanthines and leukotriene receptor antagonists. 90% of R03

prescriptions included 11 active substances or combinations. Inhaled

glucocorticoids are the most prescribed off-label, with 19% in terms

of age and 56% in terms of indications for use. The largest number

of off-label drugs was in children younger than 2 years [18].

In the cohort study, conducted in the Netherlands, the largest

number of prescribed drugs - off-label and unregistered - was also

the largest in the group of children aged 1 month to 2 years. The

one-year cumulative risk of off-label and unregistered drugs is 45%,

among children with at least one prescription for a respiratory drug

[19].

In a prospective study, which lasted from February to March 2000, at

the Children's Clinic in Great Britain, in the intensive care and

acute care wards, analgesics used in children were classified into

those used in accordance with the marketing authorization and those

are applied off-label, in accordance with the valid drug registries

in the UK. The study included 715 prescriptions, of which 67% were

licensed drugs, prescribed in accordance with the summary of product

characteristics, and 33% were licensed drugs, but prescribed outside

the use permit. Diclofenac, pethidine and morphine are mostly

prescribed off-label, while drugs are most often prescribed

off-label, in terms of dose. The high percentage of off-label use of

this drug, shown in this study, is explained by the fact that

diclofenac is not approved for pain therapy in children, but that it

has been shown to be effective in adults intra- and postoperatively

[20].

The Morais-Almeida M study (2013) showed that the most prescribed

off-label drugs were nasal corticosteroids, 76% of the total number

of prescription drugs [21], while 22% were off-label antihistamines.

In other studies, off-label administration of antihistamines varied

between 4.5 -43%. Cetirizine, levocetirizine and loratadine have

been most studied in terms of long-term safety when used in the

pediatric population. Despite pharmacokinetic studies conducted for

next-generation antihistamines, long-term safety studies in children

are lacking [22].

A study conducted in three European countries, Italy, Great Britain

and Greece, evaluated the off-label use of antibiotics, as the most

frequently prescribed drugs for children. The number of prescribed

drugs with an unregistered dose was high in all three countries in

the neonatology departments, but the number was significantly higher

in Italy compared to the United Kingdom. Antibiotics that are most

often prescribed outside the recommended dose are aminoglycosides,

specifically amikacin and gentamicin. The most common clinical

indication for use outside the recommended range is suspected or

confirmed diagnosis of sepsis, although significant use of drugs

outside the recommended doses in medical prophylaxis was more common

in Italy and Greece, compared to the United Kingdom. The most

frequently prescribed antibiotics prescribed outside the registered

indication are fluoroquinolones in Great Britain and ampicillin and

gentamicin in Italy and Greece, while the most common indications

were suspected sepsis or diagnosed sepsis.

In the pediatric ward, antibiotics most commonly prescribed outside

the registered dose are amoxicillin clavulanate in Italy, cefuroxime

in Greece, and gentamicin in the United Kingdom. Doses were higher

than recommended in Italy and Greece and lower than recommended in

the UK. The most common dosages outside the registered

recommendations were indications - sepsis, lower respiratory tract

infections and surgical prophylaxis in all three countries,

regardless of prevalence. Off-label in terms of dose was most common

in the group of children aged 28 days - 23 months [23].

The use of anticancer drugs is precisely described in the drug

authorization in terms of the type or subtype of the tumor and the

length of treatment. Prescribing anticancer drugs is believed to be

often prescribed outside the use permit, while a small number of

studies have been conducted, in order to obtain a realistic state.

Prospective studies, conducted between 1990 and 2002, indicated a

proportion of off-label drug use in children and adults. Most

off-label drugs were for palliative care of patients, some were

associated with a better clinical effect and in the treatment of

specific tumors, they were part of standard therapy [24].

Table 1: Tabelar view of studies presented in this

article

CONCLUSION

According to the analysis of the literature, the prevalence of

prescribing off-label and unregistered drugs in the pediatric

population is evident and very widespread in the past in intensive

care units.

Medicines prescribed for children should be registered for use in

the pediatric population and used in accordance with approved

indications for children, whenever possible. Although there are

indications that the use of off-label and unregistered drugs has

more benefits than the risk that the use of that drug poses, this

leads to an increasing use of these drugs even when such use is not

justified, ie. it may be less effective or harmful.

The lack of indications for use in children, in relation to the dose

or inadequate formulation for the pediatric population may prevent

children from receiving effective therapy or may lead to errors in

the routes of administration of the drug.

The increase in the prevalence of off-label drug use suggests that

legislative, regulatory initiatives are not sufficient to improve

drug use in children. Aspects of behavior and knowledge related to

off-label prescribing as well as efforts to integrate evidence into

practice must also be assessed and consolidated as part of a joint

effort to reduce prescribing gaps for children.

It is necessary to take measures for a more rational use of

medicines in pediatrics, which include the collaboration of health

workers in order to provide medicines for children that are proven

to be effective, high quality and safe to use.

REFERENCES

- Goločorbin-Kon S. i dr. Lekovi u prometu 2014. Novi Sad:

OrtoMedics

- Bajčetić M, Uzelac Vidonja T. Raspoloživost, efikasnost i

kvalitet lekova u pedijatriji, Arhiv za farmaciju 2012, 62:

279-87.

- Krajnović D, Arsić J. Etička pitanja u pedijatrijskim

kliničkim studijama: izazovi i problemi kod pacijenata sa retkim

bolestima. JAHR 2014; 10: 277-89.

- Krajnović D. Etički i društveni aspekti u vezi sa retkim

bolestima. U: Drezgić R, Radinković Ž, Krstić P (ured.) Horizont

bioetike: moral u doba tehničke reprodukcije života, Beograd:

Univerzitet u Beogradu-Instistit za filozofiju i društvenu

teoriju 2012: 231-52.

- Mandić I, Krajnović D.Talidomidska tragedija - lekcija iz

prošlosti. Timočki medicinski glasnik 2009;34(2):126-34.

- Riedel C, Lehmann B, Broich K, Sudhop T. Improving drug

licensing for children and adolescents: position paper from the

More Medicines for Minors Symposion 8 June 2015 in Bonn.

Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz.

2016; 59:1587–92.

- Coté CJ, Kauffman RE, Troendle GJ, Lambert GH. Is

the“therapeutic orphan” about to be adopted? Pediatrics. 1996;

98:118–23.

- Rocchi F, Tomasi P. The development of medicines for

children. Part of a series on Pediatric Pharmacology, guest

edited by Gianvincenzo Zuccotti, Emilio Clementi, and Massimo

Molteni. Pharmacol Res. 2011; 64:169–75.

- Ufer M, Rane A, Karlsson Å, Kimland E, Bergman U. Widespread

off-label prescribing of topical but not systemic drugs for

350,000 paediatric outpatients in Stockholm. Eur J Clin

Pharmacol. 2003; 58:779–83.

- Nahata MC. New regulations for pediatric labeling of

prescription drugs. Ann Pharmacother. 1996; 30:1032–3.

- Suydam LA, Kubic MJ. FDA’s implementation of FDAMA: an

interim balance sheet. Food Drug Law J. 2001; 56:131–5.

- Ward RM, Kauffman R. Future of pediatric therapeutics:

reauthorization of BPCA and PREA. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;

81:477–9.

- Fain K, Daubresse M, Alexander GC. The Food and Drug

Administration Amendments Act and postmarketing commitments.

JAMA. 2013; 310:202–4.

- Hoppu K, Anabwani G, Garcia-Bournissen F, Gazarian M, Kearns

GL, Nakamura H. et al. The status of paediatric medicines

initiatives around the world—what has happened and what has not?

Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012; 68:1–10.

- Corny J, Lebel D, Bailey B, Bussières JF. Unlicensed and

offlabel drug use in children before and after pediatric

governmental initiatives. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2015;

20:316–28.

- Dijkers, M., Introducing GRADE: a systematic approach to

rating evidence in systematic reviews and to guideline

development. KT Update (1)5. Austin, TX: SEDL, Center on

Knowledge Translation for Disability and Rehabilitation

Research, 2013. Available from:

http://www.ktdrr.org/products/update/v1n5/dijkers_grade_ktupdatev1n5.pdf

- Bajcetic M, Jelisavcic M, Mitrovic J, Divac N, Simeunovic S,

Samardzic R. et al. Off label and unlicensed drugs use in

paediatric cardiology, Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 61: 775–9.

- Jong G.W. T, Eland I.A, Sturkenboom M.C.J.M,van den Anker

J.N, Stricker B.H.C. Unlicensed and off-label prescription of

respiratory drugs to children, Eur Respir J 2004; 23: 310–3.

- Baiardi1 P, Ceci1 A, Felisi M, Cantarutti L, Girotto S,

Sturkenboom M. et al. In-label and off-label use of respiratory

drugs in the Italian paediatric population, Acta Peadiatrica

2010; 99: 544–9 .

- Conroy S, Peden V. Unlicensed and off label analgesic use in

paediatric pain management, Paediatric Anaesthesia 2001, 11:

431-6.

- Morais-Almeida, M., & Cabral, A. J., Off-label prescribing

for allergic diseases in pre-school children. Allergologia et

Immunopathologia 2014; 42(4): 342-7.

doi:10.1016/j.aller.2013.02.011

- Silva D, Ansotegui I, Morais-Almeida M. Off-label

prescribing for allergic diseases in children, World Allergy

Organization Journal 2014; 7:4.

- Porta A, Esposito S, Menson E, Spyridis N, Tsolia M,

Sharland M. et al., Off-label antibiotic use in children in

three European countries, Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010; 66:919–27.

- Dominique L, Off-label use of Anticancer Drugs, Lancet Oncol

2008; 9:1102-07.

|

|

|

|