| |

|

|

Introduction

Medicinal plants can be used in a raw state, but there are a lot

of products made by their processing and they are named

phytopreparations. All of them can be divided in a few categories:

cosmetics, dietary supplements (food), medical devices and

medicines. According to the Serbian Drugs Law, the herbal medicine

means a product which as an active ingredient contains one or more

plants (in total or in parts) in a dry or fresh form or their

untreated exudates; or which contains herbal preparations (got by

pharmaceutical-technological treatment of herbal material) or a

combination of these two categories. Except herbal medicines, in the

group of medicines that contain the herbal material as active

ingredient we can find traditional herbal medicines and homeopathic

medicines. Magistral and galenic medicines are specific groups of

medicines which can contain the herbal material as active ingredient

too [1]. It is important to note that medicines which contain

isolated phytomolecules do not belong to the group of herbal

medicines.

Due to their complex content, the formulation of herbal medicines is

very demanding from pharmaceutical-technological and posological

standpoint. They often have several constituents responsible for the

pharmacological effect, which, sometimes, are not fully recognized

[2.3]. However, only herbal remedies prepared in accordance with the

principles of rational phytotherapy have acceptable quality, which

then guarantees their safety and efficiency [4]. This implies the

formulation of the dosage form with precisely defined active

principles and their standardization [5]. Phytopreparations that are

registered as herbal medicines should meet these requirements to the

fullest extent.

Common problem with preparations that as active principle contain

plants or their products is a lack of evidences of efficiency. The

possible reason for this is opportunity registration as

non-medicines, and this only requires a safety certificate in most

countries. However, there are studies that unambiguously confirm the

efficacy for precisely defined indications of these group medicines.

This creates the opportunity for bigger use of these drugs, and

prescribing effective therapy with a reasonable level of side

effects, of which patients would have the most of benefit [6,7].

In general, clinical efficacy of these medicines is less than

evidenced efficacy in in-vitro conditions often due to the

undesirable biopharmaceutical profile of active constituents. Poor

lipid solubility and improper molecular size influence the final

bioavailability, and consequently lead to reduced pharmacological

efficacy. Great therapeutic potential of plants can be utilized by

applying a novel drug delivery system during formulation of herbal

medicines. The novel formulations have a significant advantage

compared to the conventional formulations. Beside to efficacy, these

systems improve other two standards important for each medicine:

safety and quality. They are good enhancers of biopharmaceuticals

properties (solubility and permeability) and efficacy. They also

facilitate delivering active constituents to the pharmacological

target. Additionally, the novel drug delivery systems decrease

toxicity, thus increasing the safety of herbal medicines. They

protect from physical and chemical degradation and enhance stability

[8] Some of existing novel drug delivery systems which can be used

for formulation of herbal medicines are:

Liposomes

Liposomes are created from one, several or multiple concentric

bilayer membranes and hydrophilic core. They belong to the group of

colloid, bearing in mind that sizes of their particles are between

0.05 and 5 μm in diameter. The main advantage of liposomes is the

ability to deliver almost all groups of molecules: hydrophilic,

lipophilic, macromolecules and small molecules. This can be

especially important for herbal extracts containing a complex

mixture of compounds [8-10].

Phytosomes

Phytosomes involve the formation of a chemical bond between the

bilayer membrane component and the plant extract component. This

leads to a significant increase in absorption. The difference in

relation to liposomes is that the active principle here is an

integral part of the membrane [11,12].

Ethosomes/Transferosomes

Ethosomes are built from phospholipids and high concentrations of

ethanol (20-45 %). Beside to ethanol, transfersomes are composed of

surfactants that facilitate delivery of medicines. These systems are

excellent carriers in transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDS)

because successfully broke barrier function of skin [8-10].

Microemulsions

Emulsions are biphasic systems in which one phase is dispersed in

other phase. One phase must be water (or aqueous phase), while other

one must be oily liquid (non-aqueous). Generally, we can divide

emulsions by size of dispersed phase at: ordinary emulsions (0.1-100

μm), micro-emulsions or nano-emulsions (10-100 nm), and

sub-micro-emulsion or lipid emulsions (100-600 nm). Micro-emulsions

are thermodynamically stable and they are suitable carriers for

lipophilic medicines [8-9].

Nanocapsules and Nanospheres

These novel drug delivery systems belong to a group of polymeric

nanoparticles (PNPs) and they are made by biocompatible and

biodegradable polymers. The nanospheres have a matrix form in which

the active principle is located, and the nanocapsules are made of

two separate parts: membranes and core in which the active principle

is. This type of novel system is excellent in overcoming the lack of

conventional dosage forms. They significantly increase the efficacy

and reduce a required dose [12-14].

The aim of the study was to determine the specificity of herbal

medicines present on the market of Serbia in the period from 2006 to

2016.

METHOD

Data which were used in the study were taken from the official

website of Agency for Medicines and Medical Devices of Serbia.

Annual reports on the Turnover and Consumption of Medicines Intended

for Human Use (Chapter 7b: Natural and financial overview of the

achieved turnover of herbal medicines in the Republic of Serbia,

according to the Anatomical and Chemical Classification of Herbal

Medicines (HATC) and the International Unprotected Drug Name (INN))

were observed for the period from 2006 to 2016 (these reports have

been available online so far) [15-25]. Data about consumption were

delivered to the agency by drug manufacturers or their

representatives. Marketing Authorization Holder gives data about

prices of medicines whose regime for issuing is without physician's

prescription.

The conversion of consumption (expressed in Serbian dinars) in euros

was made in accordance with the middle yearly exchange rate

available on the website of the National Bank of Serbia [26].

Data analysis and graph drawing were done using the Microsoft Excel

programme.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

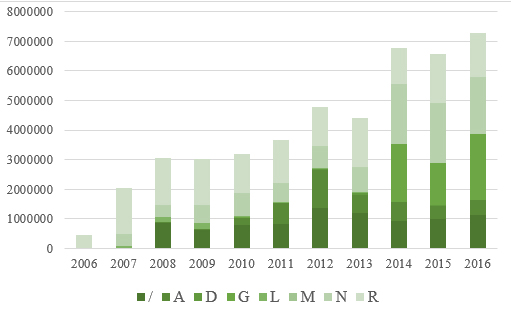

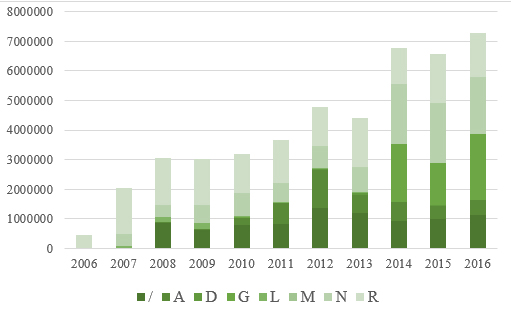

Turnover of herbal and traditional medicines in 2016 compared to

2006 was increased by 15.67 times or by 1466.33 %. Medicines from

HATC groups R, N, G (registered from 2014) and A were had the

highest turnover. Graph 1 shows turnover of herbal and traditional

medicines in the observed period.

Graph 1. Turnover expressed in euros, divided by

HATC groups

Grafikon 1. Promet izražen u eurima, podeljen po HATC grupama

A significant percentage of medicines are not classified

according to the HATC system, which points to the need for

additional efficacy studies that would facilitate the classification

of this group of drugs.

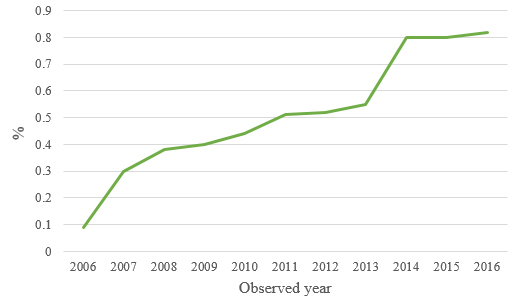

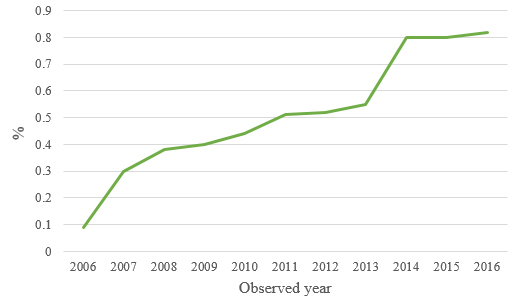

Another key point is that herbal and traditional herbal medicines

turnover were increased consumption share in total medicines

turnover (Graph 2). The share of herbal and traditional drugs in the

consumption of all medicines increased from 0.09% (2006) to 0.82%

(2016), i.e. the increase of share is by 9.11 times or by 811.11%

Graph 2. Share of herbal and traditional medicines

in total consumption of medicines

Grafik 2. Udeo biljnih i tradicionalnih lekova u ukupnoj potrošnji

lekova

An increased rate of use of plants for the treatment of various

diseases exists in the world too. Global botanical and plant-derived

drugs’ market have increasing trend and it was: $23.2 billion in

2013, $24.4 billion in 2014 and $25.6 billion in 2015. It is

expected that it will be $35.4 billion in 2020 and will have a

compound annual growth rate of 6.6% from 2015 to 2020 [27]. It is

known that about 80% of people in developing countries use plants

for treatment, but there is a significant rate of use of these drugs

in developed countries. Research says that more than 50% of the

population of developed countries (Europe, North America) use herbal

medicine at least once in their lifetime [28]. In Germany and

Canada, this percentage is between 70% and 90% [29]. Such a trend

does not surprise because, apart from the low rate of side effects

(in short-term use), good efficacy, low cost and good compliance,

herbal medicines could potentially be used for the formulation of

preparations for the treatment of very serious diseases such as

asthma [30], HIV infection [31] or cancer [32].

It is suggested that the reasons for the increasing trend in the use

of herbal remedies may be: consumer preferences for natural and

alternative therapies, dissatisfaction with conventional therapy,

affinity for self-medication, low cost, belief that these drugs are

more effective and less dangerous, but also the modernization of

pharmaceutical forms [33]. In addition, because these drugs belong

to the group of OTC products for which advertising is permitted, an

increasing number and quality of advertisements lead to increased

use [34].

At the same time, the increase in the use of herbal medicines in

Serbia is characterized by a poor knowledge about this group of

medicinal products [35].

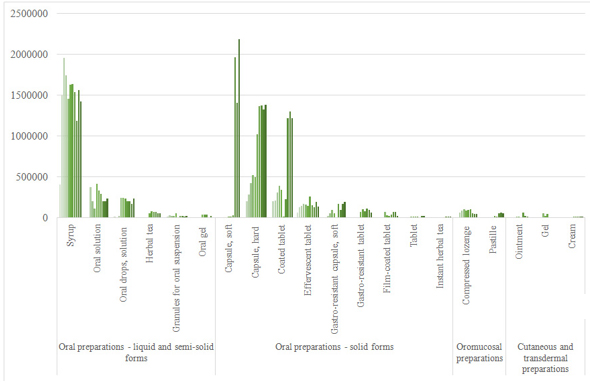

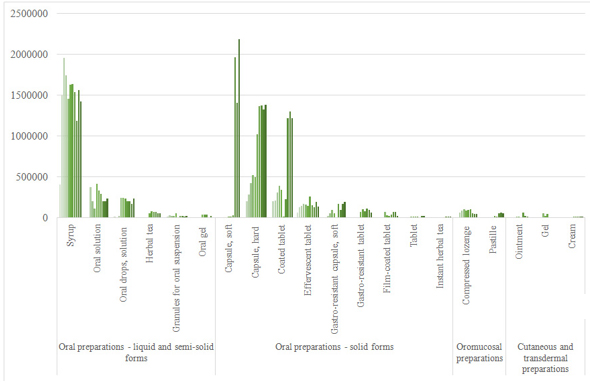

Analyzed data of used pharmaceutical forms in the observed period

are shown in graph 3. As can be seen, there is downward trend in

turnover of liquid pharmaceutical dosage forms, and upward trend

turnover of solid forms. Generally, liquid forms are less stable

than solid and additionally solid forms are more acceptable for use

in most people. Soft capsules had the highest consumption

(especially in the last observed year), and topical preparations had

very low turnover. When we talk about oromucosal preparations,

compressed lozenges had higher turnover, but with downward trend,

the opposite of pastilles.

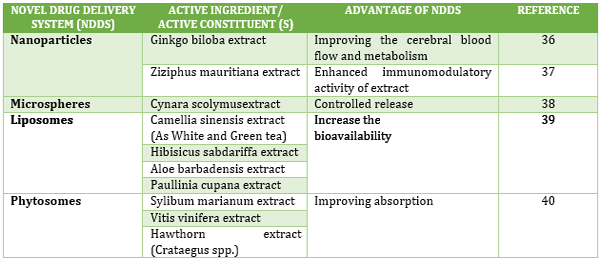

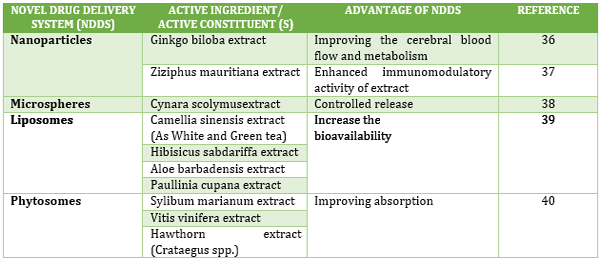

This significant increase in the use of herbal medicines was not

followed by an increase in the presence of contemporary

pharmaceutical dosage forms, since in the observed period there were

no registered herbal (or traditional) medicines formulated by novel

drug delivery system. Definitely, we can say that modern forms of

herbal medicines are not the cause of increasing their use. In other

countries herbal products formulated with the help of novel drug

delivery systems are not just part of the scientific researches, but

they also exist in the market. Some of them are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Existing modern forms of herbal

preparations in other countries

Tabela 1. Postojeći moderni oblici biljnih preparata u drugim

zemljama

Graph 3. Turnover of different dosage forms of

herbal (and traditional) medicines

Grafik 3. Promet različitih oblika doziranja biljnih (i

tradicionalnih) lekova

CONCLUSION

Improving the quality of health care implies the application of

guidelines for rational pharmacotherapy and phytotherapy. This

implies giving the right medication, in the right dose for the right

patient, right time and right route. Following the trends of

developed countries (primarily Germany), the use of herbal drugs

could be even greater. If herbal medicines on the Serbian market

should be formulated according to the latest scientific research,

the effectiveness of these drugs would be even greater.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Grants of the Ministry of Education,

Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia,

projects No 172058 and No 41012.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES:

- Zakon o lekovima i medicinskim sredstvima. Službeni glasnik

RS, 2010, br. 30 [in Serbian]. Available at:

www.lat.rfzo.rs/down load/zakon_lekovi-lat.pdf.

- Schulz V, Hansel R, Tyler VE. Rational phytotherapy. A

physician’s guide to herbal medicine. 4thedn. Springer-Verlag.

Berlin. 2001.

- Kunle, FolashadeO,Egharevba, Omoregie H, Ahamadu, Ochogu P.

Standardization of herbal medicines-A Review. Int J

BiodiverConser. 2012;4(3):101-12.

- Colalto C. What phytotherapy needs: Evidence-based

guidelines for better clinical practice.Phytother Res. 2018

Mar;32(3):413-25.

- Djordjevic SM. From Medicinal Plant Raw Material to Herbal

Remedies. In: Aromatic and Medicinal Plants-Back to Nature 2017.

InTech.

- Ernst E. The efficacy of herbal medicine–an overview.

FundamClinPharmacol. 2005 Aug;19(4):405-9.

- Maiti B, Nagori BP, Singh R. Recent trends in herbal drugs:

a review. IntJ of Drug Res and Technol. 2017 Apr 25;1(1).

- Saraf S. Applications of novel drug delivery system for

herbalformulations. Fitoterapia. 2010;81(7):680-9.

- Chaturvedi M, Kumar M, Sinhal A, Saifi A. Recent development

in novel drug delivery systems of herbal drugs. Intl J Green

Pharm. 2011;5(2).

- Ambwani S, Tandon R, Ambwani TK, Malik YS. Current knowledge

on nanodelivery systems and their beneficial applications in

enhancing the efficacy of herbal drugs. J ExpBiolAgric Sci. 2018

Feb 1;6(1):87-107.

- Singh B, Awasthi R, Ahmad A, Saifi A. Phytosome: most

significant tool for drug deliveryto enchance

thetherapeuticbenefits ofphytoconstituents. J Drug Deliv Therap.

2018 Jan 15;8(1):98-102.

- Patil RY, Patil SA, Chivate ND, Patil YN. Herbal Drug

Nanoparticles: Advancements in Herbal Treatment. Res J

PharmTechnol. 2018;11(1):421-6.

- Khalil NM. Phytosomes: A Novel Approach for Delivery of

Herbal Constituents. 2018.

- Ramos MA, Da Silva PB, Spósito L, De Toledo LG, Bonifácio

BV, Rodero CF, Dos Santos KC, Chorilli M, Bauab TM.

Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems for control of

microbial biofilms: a review. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:1179.

- *Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2006. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2007.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2007. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2008.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2008. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2009.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2009. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2010.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2010. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2011.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2011. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2012.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2012. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2013.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2013. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2014.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2014. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2015.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2015. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2016.

- Radonjić V. Promet i potrošnja gotovih lekova za humanu

upotrebu u 2016. godini. Beograd: Agencija za lekove i

medicinska sredstva Srbije. 2017.

- National Bank of Serbia [Internet]. Exchange Rate Lists For

a Specifi c Period. [cited 2018 Nov 11]. Available at:

http://www.nbs.rs/export/sites/default/internet/english/scripts/kl_period.html.

- BCC Research report. Botanical and Plant-derived Drugs:

Global Markets. Report Buyer. (Accessed Aug 2015). 2015.

Available at:

https://www.reportbuyer.com.

- **Gunjan M, Naing TW, Saini RS, Ahmad A, Naidu JR, Kumar I.

Marketing trends & future prospects of herbal medicine in the

treatment of various disease. World Journal of Pharmaceutical

Research. 2015;4(9):132-55.

- Khan MS, Ahmad I. Herbal Medicine: Current Trends and Future

Prospects. InNew Look to Phytomedicine 2019 Jan 1 (pp. 3-13).

Academic Press.

- Huntley A, Ernst E. Herbal medicines for asthma: a

systematic review. Thorax. 2000 Nov 1;55(11):925-9.

- Bekut M, Brkić S, Kladar N, Dragović G, Gavarić N, Božin B.

Potential of selected Lamiaceae plants in anti (retro) viral

therapy. Pharmacological research. 2017 Dec 16.

- Roy A, Attre T, Bharadvaja N. Anticancer agent from

medicinal plants: a review. 2017.

- Bandaranayake WM. Quality control, screening, toxicity, and

regulation of herbal drugs. Modern phytomedicine: turning

medicinal plants into drugs. 2006. pp. 25-57.

- Parle M, Bansal N. Herbal medicines: are they safe? 2006.

- Samojlik I, Mijatović V, Gavarić N, Krstin S, Božin B.

Consumers’ attitude towards the use and safety of herbal

medicines and herbal dietary supplements in Serbia.

International journal of clinical pharmacy. 2013 Oct

1;35(5):835-40.

- Shimada S. Composition comprising nanoparticle Ginkgo biloba

extract with the effect of brain function activation IPC8

Class-AA61K914FI, USPC Class-424489; 2008.

- Bhatia A, Shard P, and Chopra D, Mishra T: Chitosan

nanoparticles as carrier of immunorestoratory plant extract:

synthesis, characterization and immunorestoratory efficacy.

International journal of drug delivery 2011; 3:381-5.

- Gavini E, Alamanni MC, Cossu M, Giunchedi P. J Microencapsul

2005;22(5):487–99.

- Liposome Herbasec® [Internet]. Liposomal encapsulated,

standardized botanicals in powder form.[Cited 2018 Nov 16]

Available at:

https://www.in-cosmetics.com/__novadocuments/2319

- Integrative Therapeutics [Internet]. Super milk thistle ® X.

[cited 2018 Nov 16]. Available at:

https://www.integrativepro.com/Products/Gastrointestinal/Super-Milk-Thistle

|

|

|

|