| |

|

|

INTRODUCTION

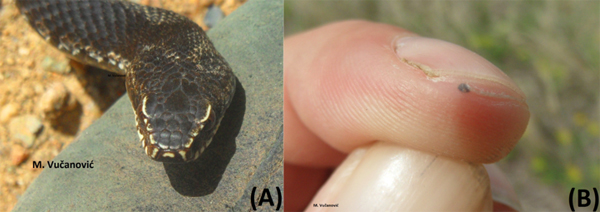

In Serbia, only three species of venomous snakes exist, each with

one or two subspecies: the nose-horned viper (Vipera ammodytes), the

adder (V. berus), and the meadow viper (V. ursinii) [1-4]. All are

strictly protected or protected by law [5]. In our country,

including the surroundings of the city of Vršac (Banat region,

Vojvodina province, northeastern Serbia), the Balkan adder, Vipera

berus subsp. bosniensis occurs (Figure 1A,B) [1,2,6]. Another viper,

V. ammodytes, widely distributed south of the Danube and Sava

rivers, also was recorded approximately 40 kilometers to the south

from Vršac [7]. The experts did not exclude the possibility that in

rare remnants of steppe habitats in Vojvodina the third viper

occurs, V. ursinii, subsp. rakosiensis [1].

Figure 1. Vipera berus bosniensis from the Vršačke

planine Mts.: A) an adult in the open, and B) a specimen well hidden

in dry grass (Photos: Milivoj Krstić).

Slika 1. Vipera berus bosniensis sa Vršačkih planina: A) odrasla

jedinka na otvorenom i B) jedinka dobro sakrivena u suvoj travi

(Fotografije: Milivoj Krstić).

According to the World Health Organization, two of the vipers

present in Serbia are medicinally important – the nose-horned viper

and the adder; the meadow viper is only moderately harmful to humans

[8].

The venoms of adder and nose-horned viper differ in composition and

effects [9]. Neurotoxic effects of adder venom are known for a long

time, as are the differences in venom composition and in

consequences of envenomation between two of the adder subspecies

present in the Balkans, V. b. berus and V. b. bosniensis [10,11].

Resulting from the distribution patterns of the species, bites by V.

ammodytes are more frequent than those by V. berus in all

ex-Yugoslav countries for which the overview publications could be

found [Nikolić, unpublished].

In Serbia, bites by venomous snakes do occur every year [Nikolić,

unpublished], but their analyses are not being performed and made

publicly available. A central register of the incidences of venomous

snakebites still does not exist in Serbia: its making was initiated

only in 2018, and the collected data were not available at the time

of this manuscript preparation [12].

In general, published information concerning the bites of Vipera b.

bosniensis are almost inexistent. Detailed case reports from the

neighboring countries date back only to the 2010s [11,13,14]. On the

other hand, the first adder bites in Vojvodina were described by a

medical professional already in 1901 [15], although from the Fruška

gora Mt., Srem region. Only one publication was found regarding

adder bites in the Vršac area, presenting six cases [16]. Between

these two reports, a 100-years gap exists. After the year 2000,

nothing of a kind was published for Vojvodina: several other cases

previously treated in the Vršac hospital were not presented in the

scientific literature. In general, in Serbia, only two additional

publications were found concerning venomous snakebites, regarding V.

ammodytes [17,18]. Importantly, no fatal outcomes were recorded.

People often cannot recognize snake species, but in our case, no

doubts existed regarding the identification of the “culprit”: the

professional was bitten, who clearly recognized the species.

With this case report, we intended to contribute to the collecting

and publishing of the data regarding the seriously neglected

venomous snakebites.

CASE REPORT

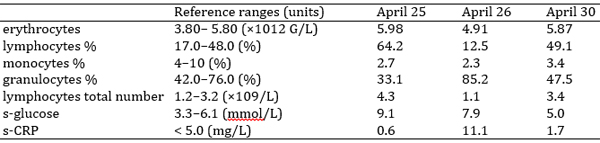

On April 25, 2019 at around 10:40 a.m., one of the authors, an

experienced 43-year old field investigator, ranger in the Landscape

of Outstanding Features “Vršačke planine”, encountered an adder and

wanted to photograph it, for the documentation. It was a sub-adult

almost melanistic male (Figure 2A). Although well aware of the

potential threat and despite handling the snake with due caution,

for a moment his attention dropped and the snake bit him at the tip

of his left-hand middle finger. The single fang only scratched the

skin under the nail (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. A) The snake that inflicted the bite; B)

tip of the patient’s left-hand middle finger a week after the bite

(Photos: Milivoj Vučanović).

Slika 2. A) Zmija koja je nanela ujed; B) vrh srednjeg prsta leve

ruke pacijenta nedelju dana nakon ujeda (Fotografije: Milivoj

Vučanović).

The patient squeezed and intuitively sucked the bite wound and

probably ingested a bit of venom. During the first ten minutes,

there was no reaction to the bite. After those ten minutes, “an

initially unidentifiable change in the body” was felt. The injured

man started driving his car towards the hospital by himself but

accompanied by a colleague. Along the way he felt sudden exhaustion

and noted that the colors of the surroundings had changed, i.e.

brightened (the sky was brightly shining, leaves turned fluorescent

green, the road shimmered like ice). The hospital was reached after

about 35 minutes.

On admission, approximately 40 minutes after the bite, the patient

was sweating and he complained of nausea and exhaustion but was able

to explain what happened. He sat on the chair and vomited for the

first time. Since he was unable to stand alone, he was put in a

wheelchair. While being driven to the Infectious diseases

department, he was unable to keep his feet lifted.

Of average osteomuscular build, he was conscious, oriented in space,

time and towards faces, afebrile, acyanotic, anicteric, eupneic at

rest, with no signs of hemorrhagic syndrome. His systolic blood

pressure was 80 mmHg, but the diastolic was immeasurable. He denied

chronic diseases and allergies to medications; he is a non-smoker

and does not consume alcohol. During the admission, the patient

vomited watery contents twice but he did not have diarrhea. Physical

findings on head and neck were normal; there was no strabismus or

diplopia. Auscultation showed normal breath sounds, cardiac action

was rhythmic with clear tones; TA 80/NA (still immeasurable) mmHg.

The abdomen was soft, insensitive on palpation; liver at right

costal margin, renal succussion negative. There was no swelling or

deformities on extremities, only the bitten finger was slightly

hyperemic: although the bite mark was not visible, minor swelling

and redness developed at the place of bite. The patient had no

neurologic deficits; meningeal signs were negative. Slight ptosis of

the left eyelid developed. After being put to bed, the patient

vomited three more times and had mild but uncontrollable diarrhea.

He was conscious but was too weak to talk or keep his eyes open.

Immediately after the admission, the patient received the

antihistamine Synopen (hloropiramin) i.v., and Lemod-Solu

(metilprednizolon) 80 mg. Intravenous infusions were introduced –

sol NaCl (natrii chloridi infundibile) 0.9% 500.0, sol Dextrosae

(glucose) 5% 500.0, and the Jugocilin (benzilpenicilin-prokain)

antibiotic 1,600,000IU was given i.m.

A single dose (5 ml) of the equine viper venom antiserum Viekvin®

was administered i.m. at 11:45 a.m., approximately 65 min after the

bite, at the place of bite on the hand and in the forearm. After an

hour, the patient started feeling better.

At 12:20 p.m. tension still 80/NA mmHg; infusion application

continued (sol NaCl 0.9% and sol Dextrosae 5%). Slight ptosis of the

left eyelid became evident. The patient appeared drowsy, his talk

was slow and slurry. Nevertheless, after two hours, all sensations

were back to normal, and the patient felt good, except he could not

control his eyelids.

At 13:20 p.m., the patient felt better, with TA 120/70 mmHg and

diuresis of 350 ml (the single instance from the admission, at 13

p.m.). During the afternoon the ptosis of both eyelids developed: he

could not open the eyes.

At 18:30 p.m. the patient’s TA was 140/100 mmHg. At 22:00 p.m. TA

was unchanged, and body temperature was 37.5°C. The patient was

stable.

During the first day in the hospital, the patient was given 3 l of

liquid i.v. He was not given anti-tetanus protection because he had

already received the third dose of Tetalpan in February 2018, i.e.

he was regularly vaccinated previously.

On April 26, the patient felt well, his TA was 120/80 mmHg and

diuresis 2.250 ml (from admission until 6 a.m.). Ptosis was less

prominent than on the previous day. Physical findings were normal.

On the third day, April 27, ptosis was still present but weaker: the

patient could keep his eyes open, but still did not completely

regain eyesight. Findings on the place of the bite were normal.

On April 28, ptosis receded almost completely; the patient had no

objective sight problems. On April 29, the ptosis receded

completely.

The patient was released from the hospital on April 30, the sixth

day after the bite. Although clinically well, his sight did not

fully recover: he still had trouble “sharpening” images for a couple

of seconds after turning his head. In addition, after two or three

hours of activity, his head would start aching. Subjectively, he

fully recovered after 10–12 days. The bitten fingertip remained numb

for about a month.

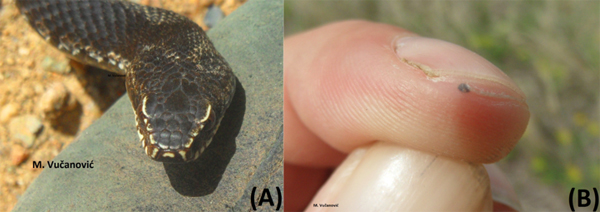

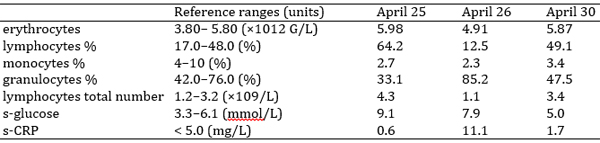

Laboratory tests: Laboratory analyses were performed at the

admission, on the second day of hospitalization and before the

patient was released. Values of the tests that departed from normal

are provided in Table 1. Other hematological, biochemical and

hemostatic parameters were within their reference ranges. Urine was

tested only on the second day, and all parameters were

normal/negative (pH, density, appearance, color, blood, bilirubin

and urobilinogen, leucocytes, ketones, proteins, nitrites, and

glucose).

Table 1. Results of laboratory analyses during the

course of hospitalization. Elevated values are given in boldface,

lowered are italicized.

Tabela 1. Rezultati laboratorijskih analiza vršenih tokom

hospitalizacije. Povišene vrednosti su podebljane, a snižene

iskošene.

DISCUSSION

Although previously healthy and practically merely scratched on

the finger with only one snake’s fang, the patient experienced

moderately severe envenomation and spent six days in the hospital.

He encountered a snake in a place that is not isolated: weekend

house owners regularly use the road he took that day – mostly in

cars, but also on foot; other types of visitors are also quite

usual. Vipera b. bosniensis is long known for its potent neurotoxic

venom, and reactions to its bites similar to the one we described

were reported from Croatia, Bulgaria, and Hungary, in addition to

the previous six cases from the Vršac hospital [11,13,14,16].

Although sometimes causing severe clinical pictures, adder bites are

rarely fatal [e.g. 19]. Importantly, the antivenin manufactured in

Serbia is effective in the cases of adder bites, although it is made

from the venom of Vipera ammodytes [17,20].

Our laboratory analyses of blood and urine did not show dramatic

aberrations from reference values. Varga et al. [14] provided a list

of papers presenting and discussing laboratory findings in the cases

of V. berus bites: among the previously reported, we found elevated

levels of glucose and CRP. We also had increases in erythrocytes,

but lowered monocytes %, while the numbers/percentages of lympho-

and granulocytes oscillated from below to above the reference

ranges. Systemic symptoms did develop but did not last for long. The

only persistent effects were problems with eyes – blepharoptosis and

vision impairment.

The cases of adder bites previously described from the surroundings

of Vršac [16] were similar to the one we reported of here. Of the

six patients treated during 18 years, three got bitten to the

fingers while attempting to catch the snakes; two sucked the wound

and one squeezed it (the remaining three did not apply the first

aid). Both local and systemic symptoms were mild to moderate, with

complications in a person suffering from asthma. All patients (22–57

years of age) received antivenin within 30 min to 4 hours after the

bite, and they spent 2–8 (4.8 on average) days in the hospital.

In general, adder bites in the surroundings of Vršac are not

frequent and they are surely not lethal, as the media like to

present them, using the phrases like “he barely survived the attack

of a snake”.

Vršačke planine Mts. are one of only several remaining lowland/hilly

habitats of Vipera berus in Serbia [1,6,21]. Like in its other

non-mountainous habitats, due to the constant spreading of human

influences, the adder is often found near the settlements and arable

land [21]. This makes it vulnerable to various anthropogenic

influences [6] and poses the potential threat to people. In Serbia,

the species is strictly protected by national legislation and was

recently designated as vulnerable; the prescribed fine for its

killing is 100.000 dinars (app. 850 €) [2,5,22].

In our case, the snake bit an experienced and cautious person, a

professional biologist, who was aware that his own mistake during

the handling of the animal led to the bite. Laypeople either fear

snakes enough to wish to kill them all, or they want to show off

trying to catch or/and torture them. Those are the situations in

which many of the bites occur [16,23,24].

CONCLUSION

Although the distribution of vipers in Serbia is comparatively

well explored, some new populations of all three species might be

“discovered” in suitable habitats, like in e.g. Hungary [25]. The

exchange of information is necessary among scientists (professionals

in biology and medicine), and between the experts and the general

public, including the media. With humble effort, proper education

could be provided to the target population and the risk of

snakebites could be minimized.

Acknowledgements

Sonja Nikolić is financed through the Project No. 173043 of the

Ministry of Education, Sciences and Technological Development of the

Republic of Serbia. Milivoj Krstić kindly allowed us to use his

photographs of the adders from the Vršačke planine Mts. This study

did not receive any specific funding. We are grateful to the

anonymous reviewer whose constructive critique and comments helped

us improve the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None.

REFERENCES

- Jelić D, Ajtić R, Sterijovski B, Crnobrnja-Isailović J, Lelo

S,Tomović L. Distribution of the genus Vipera in the western and

central Balkans (Squamata: Serpentes: Viperidae). Herpetozoa

2013; 25 (3/4): 109–32.

- Ajtić R, Tomović L. Vipera berus (Linnaeus, 1758). In:

Tomović L, Kalezić M, Džukić G, editors. Red book of fauna of

Serbia II – Reptiles. University of Belgrade, Faculty of

Biology, and Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia,

Belgrade; 2015. p. 241–7.

- Tomović L. Vipera ammodytes (Linnaeus, 1758). In: Tomović L,

Kalezić M, Džukić G, editors. Red book of fauna of Serbia II –

Reptiles. University of Belgrade, Faculty of Biology, and

Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia, Belgrade; 2015. p.

233–9.

- Tomović L, Ajtić R. Vipera ursinii (Bonaparte, 1835). In:

Tomović L, Kalezić M, Džukić G, editors. Red book of fauna of

Serbia II – Reptiles. University of Belgrade, Faculty of

Biology, and Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia,

Belgrade; 2015. p. 249–54.

- Anonymous. Pravilnik o proglašenju i zaštiti strogo

zaštićenih i zaštićenih divljih vrsta biljaka, životinja i

gljiva [Regulation on the designation and conservation of the

strictly protected and protected wild species of plants, animals

and fungi]. Službeni glasnik Republike Srbije [Official Gazette

of the Republic of Serbia] 2011; Nos. 5/2010 and 47/2011.

- Tomović L, Ajtić R, Ljubisavljević K, Urošević A, Jović D,

Krizmanić I, et al. Reptiles in Serbia – Distribution and

diversity patterns. Bull Nat Hist Mus Belgr 2014; 7: 129–58.

https://doi.org/10.5937/bnhmb1407129T

- 7. Džukić G, Kalezić M, Marković M. Poskok (Vipera

ammodytes) – autohtona zmija Vojvodine! [Nose-horned viper

(Vipera ammodytes) – autochthonous snake in Vojvodina!] Godišnji

bilten Prirodnjačkog društva Gea 2005; 5: 13.

- WHO – World Health Organization. Health Systems and

Services: Quality and Safety of Medicines – Blood Products and

related Biologicals. Available at

http://apps.who.int/bloodproducts/snakeantivenoms/database/default.htm

(Last accessed on 11 September 2019).

- Latinović Z, Leonardi A, Šribar J, Sajevic T, Žužek MC,

Frangež R. et al. Venomics of Vipera berus berus to explain

differences in pathology elicited by Vipera ammodytes ammodytes

envenomation: Therapeutic implications. J Proteomics 2016; 146:

34–47.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2016.06.020

- Radovanović M, Martino K. Zmije Balkanskog poluostrva.

Srpska akademija nauka, Naučno-popularni spisi, Knjiga 1;

Institut za ekologiju i biogeografiju, Knjiga 1. [Snakes of the

Balkan Peninsula. Serbian Academy of Sciences,

Scientific-popular writings, Book 1. Institute for Ecology and

Biogeography, Book 1] Naučna knjiga, Belgrade. 1950: p. 43.

- Malina T, Krecsák L, Jelić D, Maretić T, Tóth T, Šiško M. et

al. First clinical experiences about the neurotoxic envenomings

inflicted by lowland populations of the Balkan adder, Vipera

berus bosniensis. NeuroToxicology 2011; 32: 68–74.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2010.11.007

- Dobaja Borak M, Babić Ž, Bekjarovski N, Cagánova B, Grenc D,

Gruzdyte L. et al. Epidemiology of Viperidae snake envenoming in

central and south-eastern Europe: CEE Viper Study. In: Abstracts

from the 39th International Congress of the European Association

of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists (EAPCCT) 21–24 May

2019, Naples, Italy. Clin Toxicol 2019; 57(6): 470.

- Westerström A, Petrov B, Tzankov N. Envenoming following

bites by the Balkan adder Vipera berus bosniensis – First

documented case series from Bulgaria. Toxicon 2010; 56: 1510–5.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.08.012

- 14. Varga C, Malina T, Alföldi V, Bilics G, Nagy F, Oláh T.

Extending knowledge of the clinical picture of Balkan adder

(Vipera berus bosniensis) envenoming: The first

photographically-documented neurotoxic case from South-Western

Hungary. Toxicon 2018; 143: 29–35.

https://doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2017.12.053

- Mirković S. Kako prost narod u Fruškoj gori i Sriemu lieči

rane nastale ujedom otrovnih zmija [How laypeople in Fruška gora

and Sriem heal the wounds resulting from venomous snake bites]

Liečnički Viestnik 1901; 23: 246–8. [In Serbian].

- Častven J, Šinžar T, Kovačević D, Moroanka E, Mitrović D,

Stanivuković M. Zmijski ujedi u području Vršačkih planina –

prikaz slučajeva [Snakebites in the region of Vršac mountains –

case reports]. Acta Infectologica Yugoslavica 2000; 5: 75–82.

[In Serbian with summary in English]

- Milićević M. Prikaz bolesnika ujedenih od otrovnih zmija

lečenih od 1960. do 1968. godine / Vorstellung der Kranken die

von Giftschlangenbissen im Jahre 1960 bis 1968 behandelt wurden

[Presentation of the patients bitten by venomous snakes treated

between 1960 and 1968]. Srpski arhiv za celokupno lekarstvo1968;

96(10): 999–1006. [In Serbian with summary in German].

- Stojanović M, Stojanović D, Živković Lj, Živković D.

Hemoragijski sindrom kod zmijskog ujeda [Hemorrhagic syndrome in

snakebite]. Apollineum Medicum et Aesculapium 2007; 5(3-4):

8–10. [In Serbian with summary in English]

- Tranca S, Cocis M, Antal O. Lethal case of Vipera berus

bite. Clujul Med 2016; 89(3): 435–7.

- “Torlak” Institute of Virology, Vaccines and Sera, Belgrade,

Serbia. User’s manual for Viekvin®:

www.torlakinstitut.com/pdf/Viekvin-en.pdf

- Nikolić S, Simović A. First report on a trichromatic lowland

Vipera berus bosniensis population in Serbia. Herpetol Conserv

Bio 2017; 12(2): 394–401.

- Anonymous. Pravilnik o odštetnom cenovniku za utvrđivanje

visine naknade štete nedozvoljenom radnjom u odnosu na strogo

zaštićene i zaštićene divlje vrste [Regulation on the

compensation charges for the damages caused by illegal actions

towards strictly protected and protected wild species]. Službeni

glasnik Republike Srbije 2010; No. 37/2010.

- Stahel E, Wellauer R, Freyvogel TA. Vergiftungen durch

einheimische Vipern (Vipera berus und Vipera aspis). Eine

retrospektive Studie an 113 Patienten [Poisoning by domestic

vipers (Vipera berus and Vipera aspis). A retrospective study of

113 patients]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1985: 115(26): 890–6. [In

German with abstract in English]

- Warrell DA. Treatment of bites by adders and exotic venomous

snakes. BMJ 2005; 331: 1244.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7527.1244

- Malina Т, Schuller P, Krecsák L. Misdiagnosed Vipera

envenoming from an unknown adder locality in northern Hungary.

North-West J Zool. 2011; 7(1): 87–91.

|

|

|

|